French soldiers from Operation Barkhane stand at attention as they wait for the handover ceremony of the Barkhane military base to the Malian army in Timbuktu, on December 14, 2021. Photo: Florent Vergnes/AFP

France and its partners’ decision to withdraw their troops from Mali after nearly 10 years of fighting a jihadist insurgency echoes the recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan. However, this situation may present an opportunity to defy the adage “history repeats itself”. A recent joint statement, signed by France, European and African allies declared: “The political, operational and legal conditions are no longer met to effectively continue their current military engagement in the fight against terrorism in Mali.”

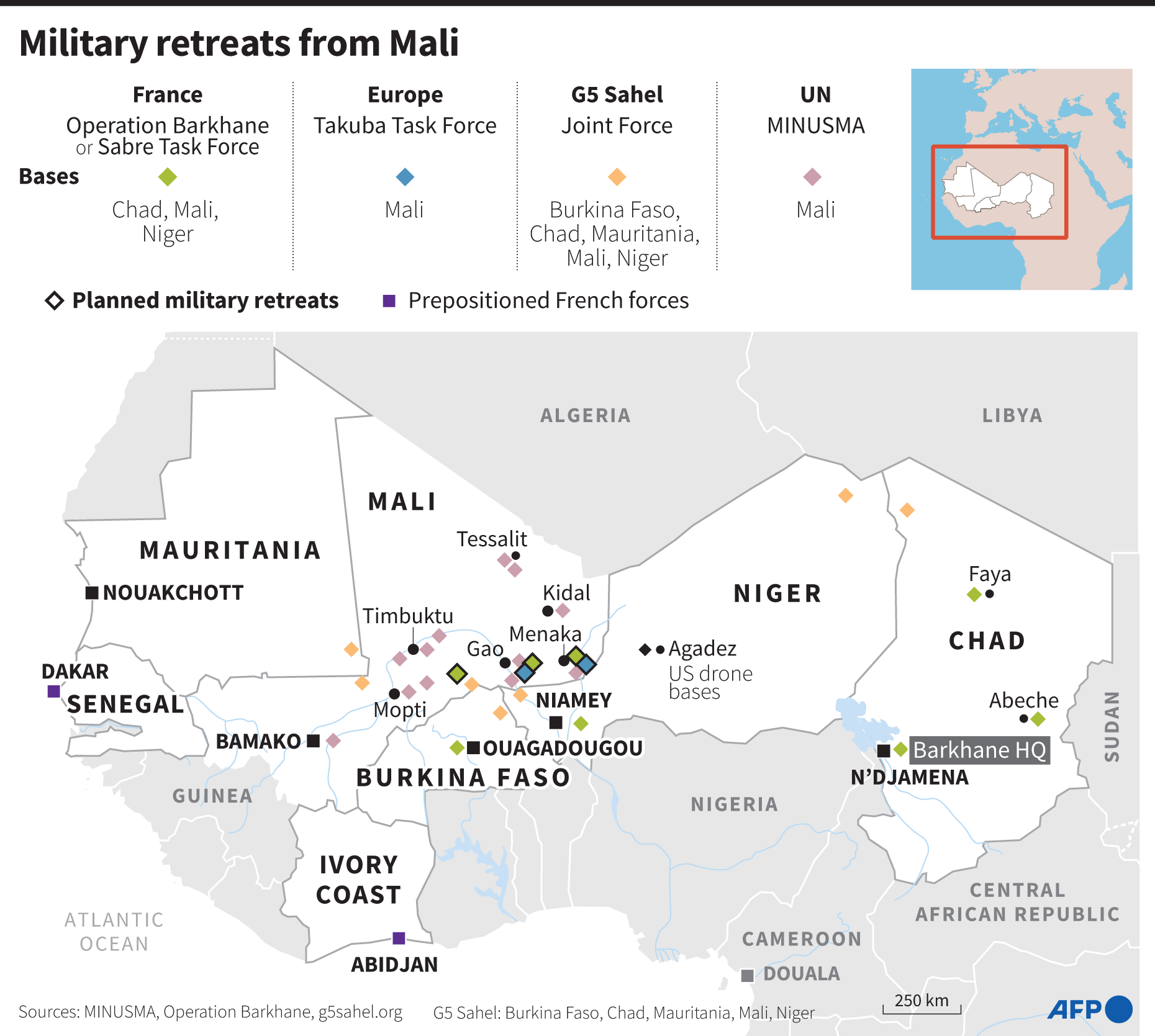

The operation has been called a “coordinated withdrawal” of French, European and Canadian forces. This decision impacts both the Operation Barkhane counter-terrorism force in the Sahel, and the 14-member European Takuba Task Force. French troops have been active against jihadists in Mali since 2013, firstly in Operation Serval and later replaced by the anti-insurgent Operation Barkhane. About 2400 French soldiers are currently deployed in Mali.

Recently, more European countries have withdrawn, indicated that they will withdraw, or have refused to deploy troops. Countries such as Denmark, which began withdrawing its troops after the junta insisted on their immediate withdrawal, and Norway, which announced that it had scrapped plans to deploy troops to Mali and Germany, have stated there is no reason to keep their troops in Mali if the country delays presidential and legislative elections.

After several years of cordial relations, France and Mali were brought together with the aim of crushing a common enemy, the jihadist insurgency, but have since seen a steady deterioration in relations. After the military junta ordered the expulsion of the French ambassador, France was spurred on to review its military presence. In addition, France found it difficult to reconcile with the military junta going back on an agreement to hold elections this month (February). Instead, the junta proposed holding on to power for another five years and hiring Russian mercenaries from the Russian paramilitary group Wagner, despite a warning from France that it would be untenable for its forces to fight alongside them.

While France and its allies will be withdrawing from Mali, they have committed to remaining in the region by continuing to conduct “joint action against terrorism in the Sahel region, including in Niger and in the Gulf of Guinea”. Niger has agreed to host the European forces as they continue to combat the jihadist militants in the Sahel.

Mali can benefit from lessons learnt from the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan so as to not create a state of crisis and uncertainty, presenting an opportunity for all relevant stakeholders involved in Mali – non-state, state, ECOWAS, and the African Union – to formulate adequate response measures to ensure the jihadist threat remains as managed and contained as possible. The following measures should be considered when planning for crisis management in Mali. It is hoped these recommendations will to some degree strengthen future crisis management responses on the continent:

Provide regular updates

French President Emmanuel Macron announced that the military withdrawal from Mali will take about four to six months, meaning that during this winding down period there may be some disruption in the response measures to the jihadists threat. To mitigate these disruptions, the stakeholder/s tasked to fill the power vacuum left by the French withdrawal must continue positive and truthful messaging to prevent a trust deficit occurring both in the country and throughout the Sahel. This strategy will curb the jihadist propaganda machinery from exploiting this situation to increase their activities.

Macron, from the time the decision to withdraw was made, has clearly articulated the reasons for the withdrawal. He claimed “multiple obstructions” created by the ruling junta meant that the conditions in Mali were no longer optimal. “Victory against terror is not possible if it’s not supported by the state itself,” said Macron.

Activate contingency plans

While some have raised concerns about the impending withdrawal, some African leaders have worked towards preparing contingency measures.

President Nana Akufo-Addo from Ghana has been steadfast in moving forward and reinforcing the importance of the UN peacekeeping force continuing its operations in Mali after the French forces’ departure. The United Nations has managed the peacekeeping mission MINUSMA since 2013.

The current Chair of the African Union President Macky Sall from Senegal called for a commitment from France and their EU partners, urging: “We have agreed with Europe that the struggle against terrorism in the Sahel cannot be the business of African countries alone, there’s a consensus on this.”

The withdrawal of forces from Mali will occur. However, measures must be formulated and implemented to safeguard the security for the greater Sahel region.

Optics are important

Before the announcement, Macron invited the Heads of States of Chad and Niger and Mauritania’s Foreign Minister to a working dinner to discuss his decision and possibly chart the way forward. As expected, the Mali and Burkina Faso coup leaders did not receive invitations to the meeting, since both nations are suspended from the African Union.

This gathering was important, as it allowed France to be seen as a committed partner in curbing the jihadist threat across the Sahel, but also an opportunity to express their grievances with the coup leaders in Mali. It appeared less a case of desertion but rather understandable frustration. By inviting the African leaders, it presented more of a collective effort with all relevant stakeholders being included in charting the way forward for the safety and protection of the region.

Manage expectations

France, EU partners and the African leaders from the Sahel have been united in the planning for the troop withdrawal. This approach is positive, as it assists in managing the public’s expectations and fears. It is crucial that a power vacuum is avoided so as not to create conditions for a fate similar to the scale and speed at which Afghanistan fell.

Intelligence sharing

With the introduction of the Russian mercenary group Wagner, and the fallout with the junta leaders, there will be a gap in intelligence gathering and sharing which could put the whole Sahel region in danger. This presents an opportunity for the European and African security agents in the task team to develop means to keep their intelligence channels open and not be caught out.

Improve early warning systems

This will be a key factor in strengthening the response measures towards curbing the jihadist threat. As the new base is being set up in Niger, it is crucial the early warning system is operationalised as soon as possible. Early warning systems have been recognised as key to identifying any escalation and or a resurgence of violent conflict, that will prove beneficial in the Sahel response efforts.

To manage the jihadist insurgency, it will become vital for the early warning analysts and decision makers to have strong links. If this is not prioritised, the link between early warning and early response will not achieve a timeous response.

Way forward

In the interests of all stakeholders operating in Mail and the Sahel, it is important to ensure that the withdrawal of troops does not create a situation for the jihadists to exploit the power vacuum and deepen the state of insecurity as was seen in Afghanistan. If response measures are well planned and implemented, it may indeed be an opportunity for the Sahel region to escape the curse of history repeating itself. Lessons learnt from the Afghanistan experience may safeguard and prevent a power vacuum for the jihadists to exploit.

[activecampaign form=1]

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.