The coup in Niger has resulted in significant regional and international fallout. On July 26, members of the presidential guard blockaded the presidential palace. Shortly after, a group of soldiers appeared on state TV to announce the formation of the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP) and the removal of democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum, citing the need to “put an end to the regime that you know due to the deteriorating security situation and bad governance”.

Later, Col Amadou Abdramane, who first announced the military takeover, declared Gen Abdourahamane Tchiani, head of the presidential guard, as the new head of state and that the constitution and other institutions had been dissolved.

Supporters of Niger’s National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP) gather at a Niamey stadium on August 6, 2023, the deadline set by the West African regional bloc ECOWAS to return the deposed President Mohamed Bazoum to power. Photo: AFP

While the CNSP has cited a deteriorating security situation as the reason behind their coup, over the last six months, the country has actually seen a 39 percent decline in terrorist attacks and political violence compared to the previous six-month period from July to December 2022. Tchiani has been head of the presidential guard since 2011 and is said to be a close ally of former President Mahamadou Issoufou. Tchiani was actually responsible for thwarting a coup in March 2021, just days before elected President Bazoum was due to be sworn in. However, it seems the relationship between President Bazoum and Tchiani had broken down recently, and there has been speculation by some that the President was considering replacing Tchiani prior to the coup.

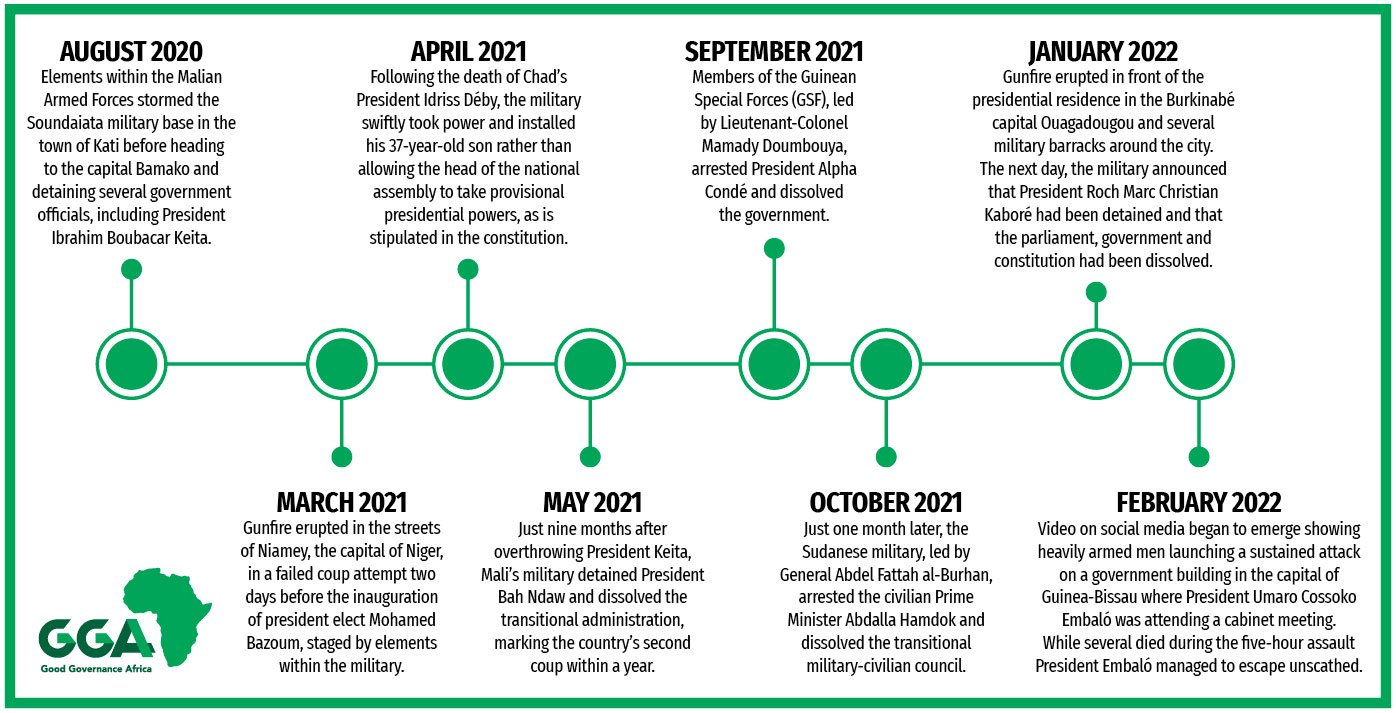

Niger’s coup is the latest in a wave of military takeovers in the Sahel which pose a major threat to democracy, peace, and security in the region. Since 2020, similar events have occurred in Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, and Mali.

Regional reaction

On 26 July, African Union Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat issued a statement condemning the coup and calling for the immediate return of the soldiers to their barracks. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) similarly took an immediate and unequivocal stance in condemning the takeover. An extraordinary summit was held on 30 July in Abuja where member heads of state called for the release of President Bazoum and his family. The body also promised to hold those responsible to account and threatened the use of “all measures necessary to restore constitutional order” including military force, if these demands were not met within seven days. A raft of measures was also applied with immediate effect, including the suspension of all commercial and financial transactions between ECOWAS member states and Niger, travel bans, asset freezes and the Nigerian government cutting off power supplies to Niger.

This will not be the first time ECOWAS has considered military action in response to constitutional crises within a member state. In 2017, ECOWAS troops entered The Gambia following President Yahya Jammeh’s refusal to step down after his loss in the 2016 presidential elections, which helped to end the crisis and restore the country to constitutional order. However, the security situation today in Niger and the wider Sahel is significantly different. In response to the ECOWAS sanctions, the Transitional Governments of Burkina Faso and Mali have expressed their solidarity with the new Nigerian coup leaders. Alarmingly, both countries have refused to uphold the sanctions and warned that any military intervention against Niger would be seen as a declaration of war against Burkina Faso and Mali.

International reaction

Both the United States and France, which have troops stationed in Niger, condemned the coup and reaffirmed President Bazoum’s legitimacy, along with the United Nations, European Union, and much of the international community. The EU’s foreign-policy chief Joseph? Borrell announced an “immediate cessation of budget support” and “suspension of cooperation in the security field.” Other regional powers in the Middle East and the North African sub-region issued statements that varied in tone and language. Algeria, Turkey, and the UAE all strongly condemned actions taken by the CNSP, labelling the takeover a ‘coup’, while Saudi Arabia and Egypt expressed “concern over developments in Niger” forgoing terming the events a ‘coup’. China similarly took a more neutral stance, emphasising the safety of its nationals.

While there was immediate speculation that Russia would support the coup, given the vocal support of Russia by members of the CNSP, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has called for a return to constitutional order, while Russia’s Ambassador to Nigeria Alexey Shebarshin has dispelled myths of Russian military support stating, “Russia opposes a military solution to the conflict, Russia has no plans to use its armed forces in Niger.” However, concerningly, the leader of the Wagner private military group Yevgeny Prigozhin was at odds with the Russian foreign ministry. In a rambling message posted to social media, the mercenary leader blamed the events on Western nations and offered the services of his Wagner soldiers to the junta. Following the mutiny by the Wagner group in June, the relationship between Wagner and the Kremlin seems to be an increasingly complex one, with unclear implications for how the Wagner group will continue to operate in Africa and globally.

Who wins and who loses?

Both the United States and France have considerable security interests in Niger. In 2022, following the 2021 Malian coup, France officially ended Operation Barkhane, a 9-year counterterrorism campaign with its base in Mali, which has widely been perceived as a failure; 1500 of those French troops now reside in Niger, which serves as France’s base of operations for its counterterrorism operations across the Sahel. France also extracts uranium in the northern Adadez region required to run the country’s fleet of nuclear power plants. France has not officially announced the withdrawal of French troops, and doing so would significantly impact the country’s ability to monitor security developments in the region. The US also currently has approximately 1200 special forces in Niger and has spent around $110 million to develop two air bases to support the use of MQ-9 Reaper drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles for intelligence operations in the Sahel.

The US and France may therefore choose to take a more pragmatic approach to dealing with the junta to protect these interests. As argued by analyst Samuel Rahmani, this approach, “which mirrors France’s historical alignment with Chad’s late dictator, Idriss Déby, or Washington’s cooperation with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, could allow Tchiani’s regime to escape international isolation.” However, choosing to do so would no doubt raise objections of hypocrisy, be in opposition to the AU and ECOWAS position, and set a dangerous precedent.

Way forward

It is critical that a zero-tolerance approach for unconstitutional changes of power be taken not only by ECOWAS and the African Union, but the wider international community. This is the only way to ensure that coup makers do not find ways of evading sanctions and maintaining a hold on power, which has been the case in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali and elsewhere on the continent when foreign state interests are prioritised over African governance. In order to deter further coups from happening, regional bodies on the continent may need to rethink their current approach and develop robust coup-proofing strategies based on a deep understanding of context-specific dynamics and triggers of coups.

- This article first appeared in Business Day on 7 Aug 2023.