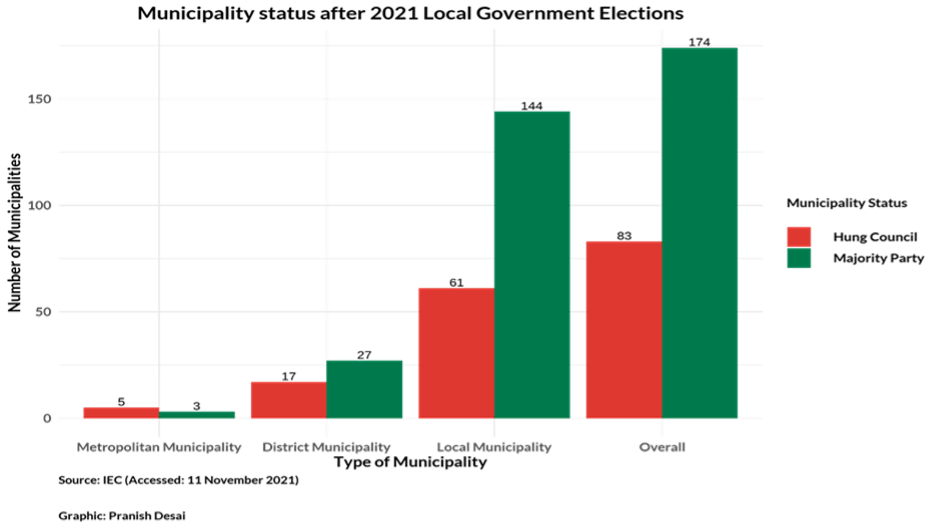

Political developments from the 1 November Local Government Elections led to 66 hung councils across South Africa: None of the competing parties managed to secure an outright majority of over 51% of the votes in these councils. The subsequent negotiations for coalitions in establishing leadership, and the agreements reached, may prove to be a seminal moment for South Africa’s political trajectory.

The African National Congress (ANC), which has enjoyed electoral dominance at all three levels of government since 1994, achieved less than 50% of the total share of the vote. This outcome placed the party in a new position, having to seek out coalition partners or join opposition benches in some councils. Similarly, the Democratic Alliance (DA), the second-largest political party, failed to capitalise on ANC governance failures and underperformed at the polls, achieving less than 22% of the total vote. Poor performance by the two largest parties respectively has placed them in a bind, and their reluctance to form coalitions with each other has led to further instability.

Members of the African National Congress (ANC) sing ahead of president Cyril Ramaphosa’s address during the party’s manifesto launch for the upcoming local government elections at the Church Square in Pretoria, on September 27, 2021. Photo: Phill Magakoe/AFP

The headache of uncertain governance outcomes is even more glaring in the country’s key metropolitan municipalities. Of the eight metros, outright majorities were only achieved in two, namely the City of Cape Town, where the DA won, and in Buffalo City, where the ANC won. The ANC retained Mangaung with a majority of one seat. As a sign of times to come, the current outcome appears poised to embed uncertainty for the next five years. Increased service delivery failures will result if the coalitions are unstable and different parties within the coalition are more focused on narrow political differences and their own interests as opposed to cooperating with their new bedfellows in advancing the country’s service delivery interests.

We (GGA) had argued for parties to put aside their political differences for the sake of advancing the country’s service delivery interests. We reiterate how the present moment demands that we not only think about the downside and risks of the coalitions formed in the wake of hung councils, but also consider the opportunities presented. For reasons provided below, if capitalised on, a clear view of the options will help carve out pragmatic pathways for stability for local governance.

In some parts of the country, it appears that the proportional representation system patterns of voter turnout and decision making may have favourably distorted the election results towards smaller opposition parties and independent candidates. Naturally, horse-trading followed the announcement of the results. Bigger parties were in self-preservation mode as they attempted to manage their electoral decline. Smaller parties were courted with promises of positions of power and power-sharing. Uniquely positioned, some smaller, hyperlocal, and narrow interest-based parties enjoyed the potential to sway the votes as kingmakers. Regional and local dynamics were a significant factor in driving many of the considerations for the negotiations.

From the outset, parties such as the Freedom Front Plus, GOOD party, ActionSA, the Inkatha Freedom Party and community forums, residents’ and ratepayers’ associations, and some independents openly declared that they do not want to work with the ANC in forming any coalitions. This position was based on the principle of punishing the ANC for its prior behaviour and chequered record, which left municipalities hamstrung and unable to fulfil their mandate of effective and efficient allocation of resources for all citizens.

Many opposition parties stayed true to their positions and kept the ANC out of several mayoral offices when voting took place in hung councils. Two notable exceptions bucked the trend, namely, the Nelson Mandela Bay and eThekwini metros, where small parties were decisive in shaping outcomes in the favour of the ANC. Firstly, in the Nelson Mandela metro, where the DA and ANC were tied neck and neck, there was an intervention by small parties including the African Independent Congress, Defenders of the People, the United Democratic Movement and Northern Alliance, among others.

These parties formed a bloc and opted to vote the ANC into power because the DA failed to meet their demands. Secondly, in eThekwini metro, an about-turn on voting out the ANC at the promise of an executive committee position by the Abantu Batho Congress, with only two seats, played an instrumental role in helping the ANC retain power in that metro.

Yet, regardless of which party is involved, hung municipalities often have severe limitations, given the nature of governance outcomes they breed. As recent history has shown, the potential to impede the realisation of good governance is glaring. In South Africa, coalitions have often become more about self-interest than the voters’ interests; they are often fraught with power grabbing moves which can subsequently, in later periods, undermine service delivery. Historically, the 2016 elections resulted in 27 hung councils, providing lessons of the shortcomings that often plague coalitions. The failures were exemplified particularly in the metros that were run by coalitions, namely in Nelson Mandela Bay, Johannesburg, and Tshwane. Over the past five years, these metros all had a high level of instability, ideological, policy and political fallouts that resulted in frequent leadership changes of mayors, speakers, and members of mayoral committees.

An unexpected outcome from this year’s LGE’s is how many hung councils have moved from formally agreed-upon coalition governments that emerged from the results of the 2016 elections, to minority-run councils where the governing party lacks the numbers to make outright decisions. A surprise turn of events saw the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and ActionSA opting to vote with the DA unconditionally without any demands in return for their vote. This strategy benefited the DA and was unexpected, as the DA did not think such an outcome would come to fruition.

The upshot is that this turn of events delivered governing power to the DA in the country’s key metros of Ekurhuleni, Johannesburg and the City of Tshwane without any concessions and obligations. This is best interpreted as a result of the collective opposition parties’ strategy to keep the ANC out at all costs. Action SA and EFF leaders explained that their primary objective was to unseat the ANC from state power and this move was calculated as part of this broader longer-term political objective, thus making tactical sense. However, if not correctly handled, the resultant minority governments could be susceptible to failures, as they often result in an impasse that may have deeper political and governance repercussions.

In practice, the election outcome has resulted in a political environment in local councils that has become highly fragmented and unstable. The coalition arrangements mean that the leading parties in these minority councils often lack the deciding vote and are forced to rely on the votes of other parties on an issue-by-issue basis for decision making. No formalised agreements, especially on key policies, were publicly made and declared. This does not bode well for accountability on all fronts.

Some party actors now have justifications for both popular and unpopular choices to their constituents, who now have no mechanism or basis from which to hold them to account. Moreover, owing to this climate, we can expect the prospect of party splits and defections to lead to internal and external collapses. Not only will some municipalities be forced into election re-runs, but they might also be forced into administration by the provincial and national governments. In this climate, parties will increasingly attempt to hold each other to ransom by vetoing council decisions, agitating for leadership change, and manipulating the diversion of resources to satisfy short-term self-interest.

As the electoral trends show, majority led councils are becoming more uncommon in South Africa. As mentioned, the absence of a majority victor has many downside risks; however, it may present a number of opportunities to promote good governance too, if correctly handled.

The absence of a clear majority in many councils may be beneficial because it allows parties to increase their influence and accomplish goals they could not achieve independently. Similarly, it provides opportunities to manage cleavages and broaden participation in government. The unique composition of hung councils can be the basis for consensus or compromise, especially valuable for policy stability issues. Parties can benefit from shared experiences and best practice lessons. This is especially needed in this country, where political lines are often polarised ideologically and service delivery disproportionately skewed in favour of loyalists. Moreover, this can be an opportunity to appoint the best-qualified candidates from across political groupings. This is important given the skills crisis that universally defines local government.

Ahead of the election, many parties promised reform, transparency, anti-corruption, and good governance. Their collective interests in this regard may be crucial to achieving the common goal of expediting the passing of much-needed service delivery implementation efforts that will benefit citizens. Although it is still early days for SA’s coalition story, these are crucial tasks, as all these parties look to the 2024 national election, which promises to be a game-changer. It is apparent that no party may achieve an outright majority at a national and provincial level in the future, thus highlighting the need for more effective multi-party governance in the present.