The consequences of South Africa’s crumbling infrastructure have been palpably witnessed in the devastation caused by the floods in KwaZulu-Natal. Furthermore, in an implicit recognition that corruption and financial mismanagement have become synonymous with government funding projects – especially at the local level – President Cyril Ramaphosa has announced there will be zero tolerance of fraud and maladministration during recovery efforts in the aftermath of this disaster.

The President’s remarks and his decision to implement a national state of disaster should be viewed in the context of the aftermath of the most contested local government elections in South Africa’s democratic history. The election saw both overall voter turnout and the vote share received by the African National Congress (ANC) fall below 50%. As a result, the state of local government in South Africa has come under increased scrutiny from many quarters of the population and spheres of civil society. This is particularly true in the case of the ANC, which lost significant ground at the local municipal level due to its checkered governance record and increasingly fears losing its majority at the national level during the 2024 elections.

Shacks affected by a mudslide can be seen at the eNkanini informal settlement in Durban, on April 22, 2022. Photo: Guillem Sartorio/AFP

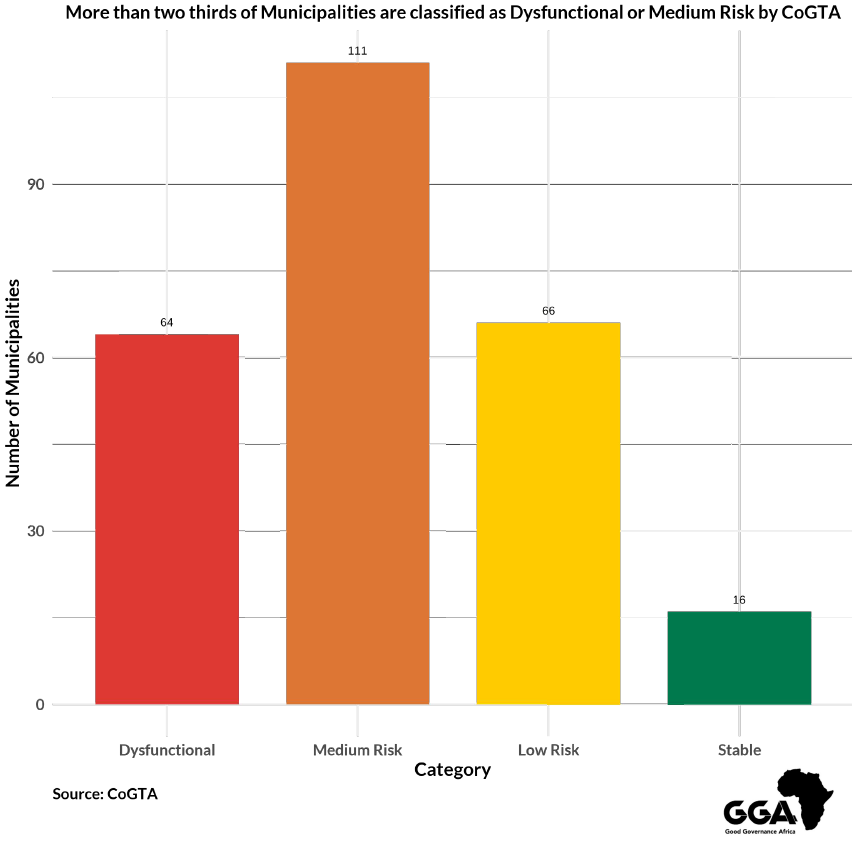

In March the President addressed the national conference of the South African Local Government Association (SALGA). He identified local government as the area in which the government has the greatest impact on people’s lives and as the “most important enabler of economic growth and development”. However, the President also lamented the state of local government, noting that just over 5% of municipalities are considered financially stable by the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (CoGTA), with 31 municipalities under administration.

This dysfunction directly affects the provision and maintenance of crucial infrastructure while also frustrating societal well-being and impeding economic development. A consequence of this is witnessed in the damage and loss of life that follows natural disasters such as the KZN floodings.

The President suggested that a substantial portion of the responsibility to rectify this dysfunction lies with the newly elected local government councils and the civil servants who work in local government offices across the country. It is certainly the case that local officials and political leaders have a key role to play in solving poor service delivery. They also have to address the widespread corruption and financial mismanagement plaguing local governments. At the same time, it is imperative that the national government and provincial governments decisively intervene to help the local government fulfil its developmental mandate as outlined by documents such as the White Paper on Local Government (1998) and the Municipal Systems Act (Act 32 of 2000). This is more so the case in areas requiring urgent interventions.

Compounding infrastructural headaches

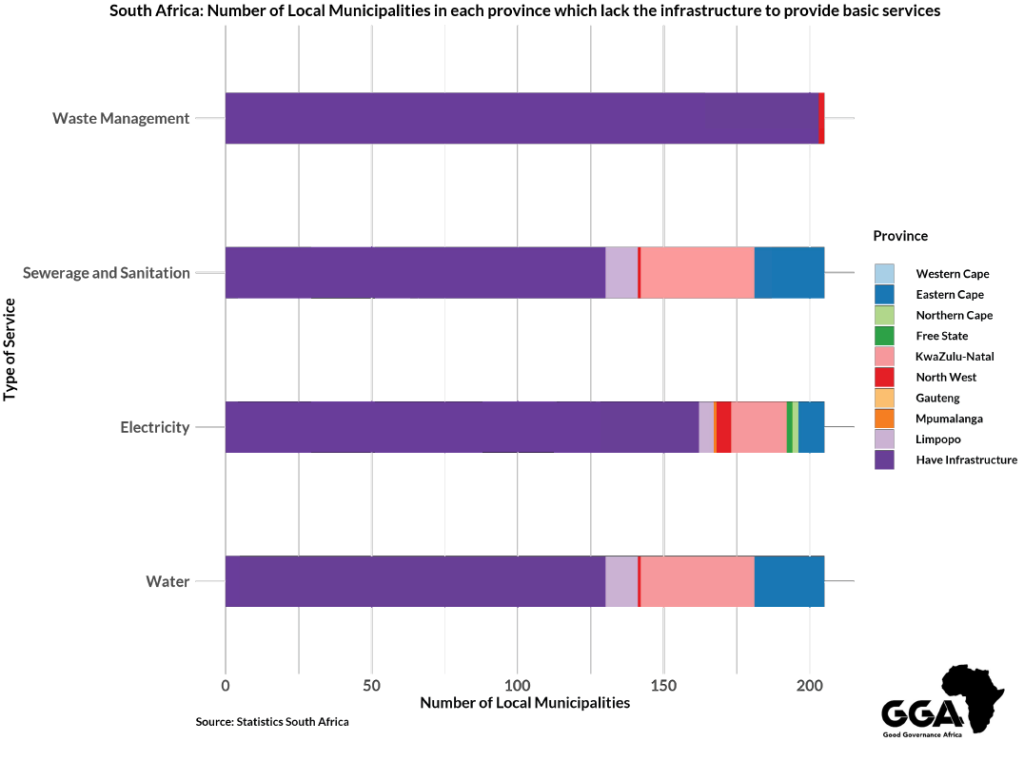

Across towns and cities, public infrastructure is afflicted by poor maintenance, regional inequalities and extensive backlogs. One of the core functions of the 205 local municipalities in South Africa is to provide basic services, including water, electricity and adequate sewerage systems to households within their boundaries. To fulfil their mandate of providing services, local municipalities need to have the necessary infrastructure. But there are severe inequities among local municipalities regarding this infrastructure.

According to the most recent (2019) Non-Financial Census of Municipalities, 43 municipalities lack the infrastructure needed to provide electricity and 75 municipalities lack the infrastructure to provide adequate sanitation systems. District municipalities and provincial governments must often step in and provide service delivery for residents in these areas, which goes against the conventional practice that basic service delivery of this kind is the primary responsibility of local municipalities.

Considering that most of these local municipalities are in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, and North West provinces, it should come as no surprise that the average performances of municipalities in these provinces were among the worst in the category of Service Delivery on the 2021 Governance Performance Index released by Good Governance Africa. To illustrate the extent of the problem, in 2021 the head of the presidency’s investment & infrastructure unit, Dr Kgosientso Ramokgopa, suggested it would take 68 years to deal with the infrastructure backlog if resources from the fiscus were used. This clearly shows that this critical task cannot be limited to the government but will need private sector partners and players to finance it, as envisaged by the National Infrastructure Plan of 2050.

The consequences of mismanagement

Municipalities are custodians of significant capital budgets within the public sector through grants such as the municipal infrastructure support grant and other conditional grants. This money is meant to be put aside for long term planned capital items, such as the construction of roads and buildings and the purchase of vehicles. Yet there are multiple problems of mismanagement that run against the core prescripts of the Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003.

First, many municipalities do not spend their grant funds, which in turn must be returned to the Treasury. For instance, the Sekhukhune District Municipality in Limpopo must return over R180 million, including R50 million of the municipal infrastructure grant, R22 million of the water and sanitation infrastructure grant and R113 million of the regional bulk infrastructure grant. All this despite the municipality having problems over the provision of water and a lack of capacity to ensure its provision. This example highlights that the problem is most acute in rural and underdeveloped municipalities, thus perpetuating inequalities.

Another core issue is the non-payment for crucial services and infrastructure at the local level. This is illustrated by the recent revenue collection campaign in Tshwane, where the municipality opted to cut electricity and services to defaulting customers. The municipality was experiencing a significant liquidity crisis that placed it at risk due to the challenges of revenue collection and debt defaults, and non-payment by national government departments, SOEs, and provincial departments. This is the case across many other municipalities that default on payments to Eskom and fail to maintain infrastructure because of non-payment of accounts by residents. The total arrear debt estimated to be owed to Eskom is R35.3 billion, with 10 municipalities alone accounting for 68% of this debt.

Another problem is using funds earmarked for infrastructure development and allocating them to cover unrelated expenditure such as bloated wage bills. According to the 2020 financial census of municipalities, for every R1 spent by South Africa’s 257 municipalities, 23c was spent on salaries. Other budget items included electricity services (13c), bad debts (4c), the provision of water services (5c), contracted services (7c), and less than 1c on repairs and maintenance.

A fundamental problem that breeds those addressed above is corruption. Often this involves overcharging through inflated prices and the flouting of the supply chain process and, at times, non-delivery. An infamous example is the Enoch Mgijima Municipality, which despite lacking running water and other infrastructure, built a poor quality stadium at a bloated and unjustified cost of R15 million. Moreover, the government’s commitment to put together at least R1 billion to help rebuild infrastructure for the people of KwaZulu-Natal has met a lack of public trust over the fear of corruption.

A second element of corruption is outright criminality, in which some municipalities or their external service providers are being held ransom by local groups that threaten to sabotage funded projects if they are not paid off. In other cases, it involves jostling by different factions within political contests, which in some cases translates to vandalism and sabotage. Often, this is deliberate and done by skilled people with insider knowledge. This was recently observed in Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay, thus reversing crucial gains in addressing the infrastructural backlog.

What can be done? Some key interventions to remedy the situation.

The current legislative framework – such as the Infrastructure Development Act 23 of 2014 – that governs investments in public infrastructure is meant to facilitate, co-ordinate and manage the provision of infrastructure. But the framework’s components are largely fragmented. This leads to a conflation of roles within multiple institutions ranging from SOEs, national departments, municipalities, and other entities. Better intergovernmental relations and coordination with other relevant stakeholders, including the private sector, can improve infrastructure planning and sustainability in local government. To put local municipalities in a position to succeed, national government and provincial governments need to not only provide local municipalities with the infrastructure required to fill their mandate, but also support them with an adhered-to governance framework, provide guidance on the regular maintenance of this infrastructure, and creating a workable asset management plan.

Transparent communication and information sharing are key to a turnaround. This will help reduce the disjuncture between national, provincial and local government administration. At a political level, it will address bickering among governing political parties. The District Development Model is a potential game-changer that aims to improve the coherence, coordination, oversight and impact of government service delivery, focusing on 44 districts and eight metros around the country. This is also touted as one of the key governance strategies in response to the KZN floods.

Ultimately, there is a need to improve the quality of local institutions, including municipal leadership, traditional authorities, and technical competence. Municipalities can start with assessments of how strongly they adhere to King IV governance principles, for one, and took steps to put those in place. We would see vast improvements in governance performance and service delivery results. Multi-sectoral interventions, including community-based organisations, business councils, industry associations, trade unions, and Chapter 9 institutions, will be crucial for addressing the present situation in response to the KZN floods. The present provides an opportunity to start improving government efficacy in addressing local government concerns about infrastructure management, which is where the bulk of the country’s governance problems lie, and therefore also the opportunity to improve its trajectory.

[activecampaign form=1]