Sub-Saharan Africa: the medical brain drain

Doctors and other medical professionals migrate for many reasons, but their absence seriously compromises health service delivery

A doctor with a loud hailer shouts slogans during a protest march by senior medical doctors in Harare, on December 4, 2019. – The doctors petitioned the Zimbabwe Parliament demanding improved working conditions and the reinstatement of 448 junior doctors fired for taking part in a two month long strike over low salaries. (Photo by Jekesai NJIKIZANA / AFP)

A brain drain of African medical staff over several decades has significantly depleted the continent’s health services of doctors and nurses. At the beginning of the millennium, approximately 65,000 African-born physicians and 70,000 African-born nurses were working overseas, according to a study by Michael Clemens and Gunilla Pettersson Gelander, published in Human Resources for Health in 2008, representing about one fifth of African-born physicians and one tenth of African-born nurses globally. The number of health workers who migrate abroad varies considerably from one country to another, but figures on the migration of African doctors and nurses to 30 OECD countries, published in a 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) policy brief, suggest that the trend has been ongoing.

Between 2000 and 2011, the number of African doctors who migrated to OECD countries rose by one third to 55,541, whereas the number of nurses more than doubled to 135,970. According to OECD health statistics, Nigeria led the list of African countries whose doctors were working in these countries in 2019, with a total of 10,487 as against 10,318 for Egypt and 9,509 for South Africa. On 25 May 2018, South African daily newspaper The Citizen quoted African Union statistics revealing that 75% of all trained physicians in Mozambique emigrate. The figures for other countries – Angola 70%, Malawi 59%, Zambia 57%, and Zimbabwe 51% – were also alarmingly high.

The trend is corroborated by sources on the other end of the migration flow. An article published on the Mo Ibrahim Foundation website on 9 August 2018, titled ‘Brain drain: a bane to Africa’s potential’, indicated that in 2015, the number of African-trained International Medical Graduates (IMGs) practising in the United States (US) alone reached 13,584, a 27.1% increase from 2005. In 2015, 86.0% of all African-educated physicians working in the US were trained in Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria and South Africa. A WHO report in 2013 warned that the world will be short of 12.9 million healthcare workers by 2035. The largest shortages are expected to be in Asia, but it is in sub-Saharan Africa where they will be especially acute. All regions will be competing for medical staff; and the demand will also be high in developed countries.

In the EU in 2013, the overall shortfall of health workers was estimated at 1.6 million and it was expected to increase to 4.1 million in 2030, according to Jean-Pierre Michel and Fiona Ecarnot, in an article published by the journal European Geriatric Medicine in April this year. African health systems will likely bear the brunt of this shortfall. Africa bears “more than 24% of the global burden of disease, but has access to only 3% of health workers and less than 1% of the world’s financial resources,” says the WHO. In 2011, the British medical journal The Lancet indicated that whereas high-income countries sustained a relatively high physician-to-population ratio, by recruiting graduates from developing regions, more than a half of sub-Saharan African countries were not meeting the minimum. For example, The US Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) World Fact book states that in 2017, only four African countries were meeting the WHO standard of one doctor for 1,000 patients: Algeria, Libya, Mauritius and the Seychelles, while Egypt and South Africa were close to it with ratios of 0.8 and 0.82 respectively.

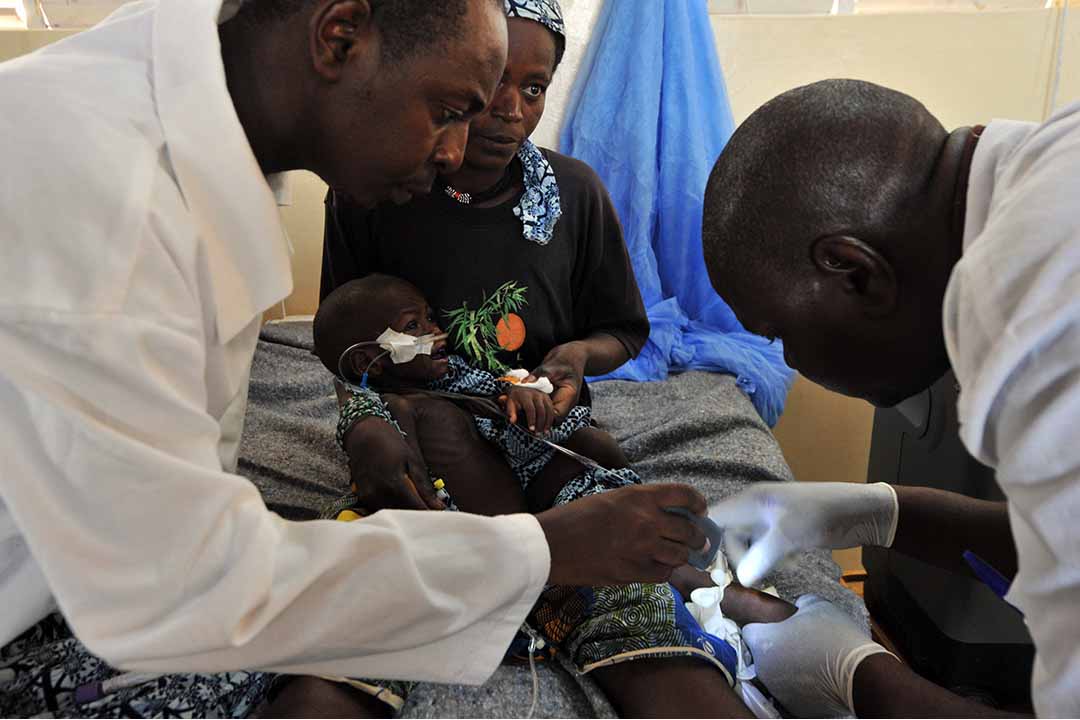

Part of the explanation for this situation is that since April 2001, when African heads of state committed themselves in the Abuja Declaration to allocate at least 15% of their budgets to improving their health sector, by 2014 only four countries (Malawi, Ethiopia, Swaziland and Gambia) met or exceeded the Abuja target, according to a 2016 WHO report, ‘Public Financing for Health in Africa: from Abuja to the SDGs’. South Africa, Namibia, Lesotho, Burundi, the Central African Republic and Kenya were close to the 15% target, but 19 other countries had spent less in percentage than was the case in 2000. The medical staff shortage crisis affects almost every facet of public health, including child and adult mortality, maternal health, and the treatment of diseases and infections. Mortality rates in Africa’s general population are among the highest in the world, with death probability rates of 39.1% for men and 33.2% for women aged between 15 and 60.

UNICEF has estimated that a child born in sub-Saharan Africa has an 8.1% probability of death before the age of five. Africa’s mortality rates are strongly related to a lack of healthcare workers within the region, a situation exacerbated by the uneven distribution of healthcare workers between urban and rural areas. Healthcare workers migrate for a variety of reasons. For many migrants, it is a personal decision. For others, it occurs in the context of cooperation agreements to train staff abroad and it is temporary. This is called circular migration and it is particularly encouraged by the European Union. Other health workers are sent abroad for training by their governments and are supposed to come back and exercise their skills back home, but end up working in European or American hospitals.

Push factors for migration include low salaries, poor living and working conditions, lack of career development opportunities, high cost of living, job and economic insecurity, and lack of social recognition. Some researchers stress a strong correlation between political instability in a country and the loss of its medical personnel. A study from the Universities of Ghana and Alberta (Canada) in 2007 found that push factors for medical personnel included an oppressive political climate, the threat of violence and the persecution of intellectuals.

Doctors tend to a child suffering from severe malnutrition sitting on his mother’s knees at the medical center of the NGO “Bien etre de la femme et l’enfant au Niger (BEFEN, Welfare of the Woman and the Child in Niger) at the Mirriah refugee camp, in the Zinder region of Niger. Mali’s March 22 military coup and the subsequent seizure of half the country by rebels have compounded the already worrying effects of a food crisis across West Africa’s Sahel region. The UN estimates the Mali crisis has forced more than 320,000 people from their homes, with 187,000 seeking refuge in neighbouring countries, including Niger — already in the grips of a new drought that has put millions at risk of hunger. AFP PHOTO / ISSOUF SANOGO (Photo by ISSOUF SANOGO / AFP)

A lack of respect from physicians, and barriers to full utilisation of specialised nursing knowledge in healthcare settings, were push factors for the migration of nurses in a Ghanaian study, according to Delanyo Dovlo, director of health systems and services at the WHO Regional Office for Africa. Another push factor is the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Nurses are particularly stressed by its impact in southern Africa. On the “pull” side, salary plays an important role. According to the United Nations publication Africa Renewal, “on average, surgeons in New Jersey earn $216,000 annually, while their counterparts in Zambia make $24,000”. Another incentive is the possibility to improve skills in the countries of destination, say researchers of the OECD Health Division, in a report on ‘Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students’, published in July 2019. Dovlo also identifies differences in the way that African doctors and nurses are recruited.

“While doctors are usually passively recruited (i.e. look for the jobs for themselves), nurses are usually actively recruited by agents, sometimes for a fee,” he says. Again, the situation varies by country and time periods. The migration of nurses from South Africa is declining, for example, partly due to a slowdown in recruitment from the United Kingdom (UK) since 2006, when new immigration rules allowed foreign nurse work permits only if employers could demonstrate non-availability of staffing from Britain and the EU. Meanwhile, migration flows have continued towards Gulf countries. The United States is the main country of destination for migrant doctors and nurses. Of all foreign-born health workers who practise in OECD countries, 42% of doctors and 45% of nurses practise in the US. The UK is the second country of destination, receiving 13% of all foreign-born doctors who practise in OECD countries, followed by Germany (11%).

This ranking is reversed for nurses, with Germany in second place (15%) followed by the UK (11%). It can be assumed that gaps in staffing significantly compromise health service delivery in sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, where the ratios of doctors and nurses to the population are very low (16 doctors per 100,000 and 88 nurses per 100,000), the migration of health professionals reduces the capacity of the remaining staff to attend their patients, note the authors of a paper titled ‘Migration of health workers in Kenya: The impact on health service delivery’, published in March 2008 by the Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa. Countries that invest in the training of health workers suffer financial losses when these professionals emigrate (including the cost of education and training). A 2018 Mo Ibrahim Foundation report on the state of public services in Africa revealed that nine countries lose about $2 billion a year due to doctors and health practitioners leaving the continent.

Destination countries, on the other hand, benefited handsomely. “One in 10 doctors working in the UK come from Africa, allowing the UK to save on average $2.7 billion on training costs, followed by the US ($846.0 million), Australia ($621.0 million) and Canada ($384.0 million). In total, these four top destination countries have saved $4.6 billion in training costs for the Africa-trained doctors they have recruited,” said the Foundation. The recruitment of African medical staff workers by high income countries has been a major concern for global health bodies for more than a decade. At the 57th World Health Assembly in May 2004, participants agreed the international migration of health personnel was “a challenge for health systems in developing countries” and urged member states to develop strategies, including better working conditions, to encourage health professionals to remain in their own countries.

In 2010, the assembly adopted the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, which, it says, “aims to establish and promote voluntary principles and practices for the ethical international recruitment of health personnel and to facilitate the strengthening of health systems”. One positive element of migration, however, is that African medical staff benefit from new skills abroad, which they can usefully share on returning to their countries of origin. Temporary migration for training and studies, especially when coordinated with support programmes of specialised entities like the Antwerp-based Institute of Tropical Medicine, may bear considerable benefits in designing strategies against pandemics such as AIDS, Ebola and COVID-19, and also boost research. One of the world’s top Ebola specialists, the pioneering Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe, practises in Kinshasa and was trained in Antwerp.

Francois MIsser is a Brussels-based journalist. He has covered central Africa since 1981 and European-African relations since 1984 for the BBC, Afrique Asie magazine, African Energy, the Italian monthly magazine Nigrizia, and Germany’s Die Tageszeitung newspaper. He has written books on Rwanda and the DRC. His last book, on the Congo River dams, is La Saga d’Inga