DRC: hasty electoral reforms

Decentralisation threatens to create more instability in this central African country

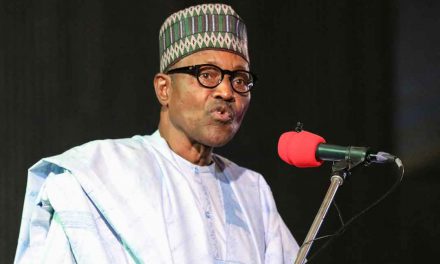

President Joseph Kabila © Helene C. Stikkel

by François Misser

On March 2nd 2015, President Joseph Kabila promulgated a law creating 15 new provinces, bringing the total to 26 as against 11. Five provinces remain as they were: the capital Kinshasa and its hinterland, Bas-Congo, North and South Kivu and Maniema. The other six provinces have been split up to create several much smaller ones.

The reform was considerably delayed. Article 2 of the constitution, adopted by referendum in December 2005 and in force from February 2006, lists all the 26 provinces. But nearly five years had elapsed since the constitutional deadline set for the creation of the new provinces expired in 2010.

The reform makes sense in many ways. The average size of the former provinces was considerable—about the size of the UK. The distance between some provincial capitals and their boundaries was enormous. Lubumbashi, the capital of the former Katanga province, was over 900 km from the border of neighbouring South Kivu, and the journey could take several days, even during the dry season, owing to the poor state of the road network.

But the reform was carried out in haste. Analysts suspected that Mr Kabila’s sudden decision to introduce the new law was aimed at justifying a postponement of the elections that would allow him to extend his term in office. According to the constitution, a president can only rule for two terms, and Mr Kabila’s second term will end in November 2016. Moreover, these critics argue that the creation of new provinces presents the country with a fait accompli and that the need for appropriate funding for the decentralisation would compete with the need to finance national elections.

In March 2015, Moïse Katumbi, the governor of the former province of Katanga told Radio France Internationale that the 2015 budget did not include funding for the creation of the new provinces. The Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) has estimated the cost of the elections, due to be held between October 2015 and November 2016, at $1.15 billion.

Another speculation is that Mr Kabila saw an opportunity to get rid of Mr Katumbi, a political rival. Mr Katumbi is thought to have presidential aspirations, but his term in office expired in June as a consequence of the March law.

Other factors indicate that the Congolese authorities may have put the cart before the horse. Article 175 of the constitution stipulates that 40% of tax revenues must go to the provinces, but it has not been implemented, nor has the government drafted and approved a decree to implement it. Only 3% of the national budget that was supposed to be allocated to the provinces was spent in 2014 and most investment projects were not implemented. The 21 new provinces (as well as the other five) will lack the financial means necessary for genuine decentralisation. This factor alone is creating considerable frustration.

In the richer provinces of Bas-Congo and Katanga (the engine of the DRC’s economy), secessionist movements are on the rise. Katanga is the largest contributor of revenues from extractive industries to the country, and contributes $1.043 billion or 68% of total tax revenues, including all extractive industries revenues and royalties from the oil and mining industries.

But the province only received $88.4m, or 5.84% of the revenues that should have been transferred to the provinces from the national treasury, according to a report by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) published in late December 2014. The current system (which does not respect Article 175 of the constitution) means that the tax administration collects the taxes and transfers the money to the central state, which redistributes only a fraction of this amount to the provinces.

Similar grievances are expressed in North Kivu. In October 2014, its governor, Julien Paluku, told UN-sponsored Radio Okapi that his province gets $600,000 per month from the central state, not the roughly $5m it should receive according to the constitution.

The sudden creation of new provinces appears to have weakened rather than strengthened provincial government. Haut-Katanga is the only new province with the skills, instruments and infrastructure needed to collect taxes. Its administration in the capital, Lubumbashi, continues to collect revenues from mining corporations. Elsewhere, new provincial tax departments still need offices, furniture and access to electricity.

Some new provinces lack administration buildings and offices. In Boende, the capital of the new Tshuapa province, the post office building now accommodates the provincial parliament, while the homes of public administration officials have become offices for the new provincial ministries. Last July, the central government told the officials who lived there to move out immediately or face expulsion.

In Nord Ubangi province, the parliament is being hosted temporarily in a motel at Gbadolite. Kenge, which used to be in Bandundu province, but is now the capital of the new Kwango province, lacks roads suitable for motor vehicles, a drinking water system and electricity. In Kasai Oriental province, civil servants went on strike in August 2015, saying their salaries had not been paid in July.

The governors and parliaments of all 21 new provinces should have been in place on August 12th, 120 days after the appointment of special committees whose task was to prepare the installation of the new provinces. As a temporary measure, reported Radio Okapi on July 30th, the parliaments of the former six provinces would be split into 21 parliaments until the provincial elections, which were originally to have taken place in 2012, but rescheduled for October 25th. The provisional offices of these new parliaments were set up in Katanga by the former elected MPs at the end of July

But the government then froze the power of the provincial parliaments in the 21 new provinces. On September 3rd, the prime minister, Augustin Matata Ponyo told the Constitutional Court the government did not have the money for governors’ elections or the installation of the new provinces. On September 8th the Constitutional Court ordered the government to take “exceptional transitional measures” to ensure order, security and the continuity of public services in the new provinces until governors and provincial governments were in place. But the Constitutional Court’s decision gave the government considerable latitude.

On October 1st, the minister of the interior, Évariste Boshab, suspended the parliaments of the 21 new provinces. In Tshuapa province, police were deployed around the parliament building in Boende to prevent MPs, who had been elected in 2006 as part of the larger former Équateur province, from accessing it. Provincial elections, which were supposed to take place on October 25th, were postponed indefinitely.

On October 29th, Mr Kabila appointed “special commissioners” to run the provinces. His justification was the above-mentioned decision by the country’s highest court, calling for “exceptional transitional measures” after the court estimated that “force majeure” and lack of funds prevented the CENI from organising the provincial and local elections as scheduled. Uncertainty prevails on the duration of the mandate of these special commissioners. The CENI did not stipulate a new date for the provincial elections.

Senator Jacques Djoli, of the opposition Movement of Liberation of Congo (MLC), says the appointment of special commissioners is “unconstitutional”. According to Article 80 of the constitution, governors must be elected by provincial MPs. But the move is no surprise. In recent years Mr Kabila has sought to gain total control over the country’s governors.

On January 20th 2011, Article 198 of the constitution, which stipulated that governors could only be dismissed by provincial assemblies, was amended. Currently, president has the power to dismiss governors by decree after consultation with the government and the speakers of the national assembly and the senate.

The former minister of defence, Charles Mwando Simba, who joined the opposition in September, says Mr Kabila opposed the election of governors because he was aware that his own candidates would not be elected by provincial MPs. Over the last few months, leaders of the seven parties of the ruling coalition, including Mr Simba’s, have defected because they oppose Mr Kabila’s bid to run for a third term in 2016, which is not possible under the present constitution.

Another major problem, stressed by Mr Simba, is that the government has created an odd situation with two systems: one in which the five unchanged provinces are still ruled according to the constitution by governors and provincial parliaments, and another in which the 21 new provinces are ruled by the new special commissioners.

The special commissioners will face many problems, including their perceived lack of credibility as political appointees. Among other things, they will have to deal with a backlog of cases of bad governance. According to Le Soft International a news outlet based in Paris, Brussels and Kinshasa, the minister of the interior has identified several embezzlement cases involving retrocession funds, or money collected by the tax authorities and redistributed by the central state.

International donors in Kinshasa are concerned that, without the appropriate resources and checks and balances, decentralisation will fail, or worse, that it will create new layers of corruption.

Francois MIsser is a Brussels-based journalist. He has covered central Africa since 1981 and European-African relations since 1984 for the BBC, Afrique Asie magazine, African Energy, the Italian monthly magazine Nigrizia, and Germany’s Die Tageszeitung newspaper. He has written books on Rwanda and the DRC. His last book, on the Congo River dams, is La Saga d’Inga