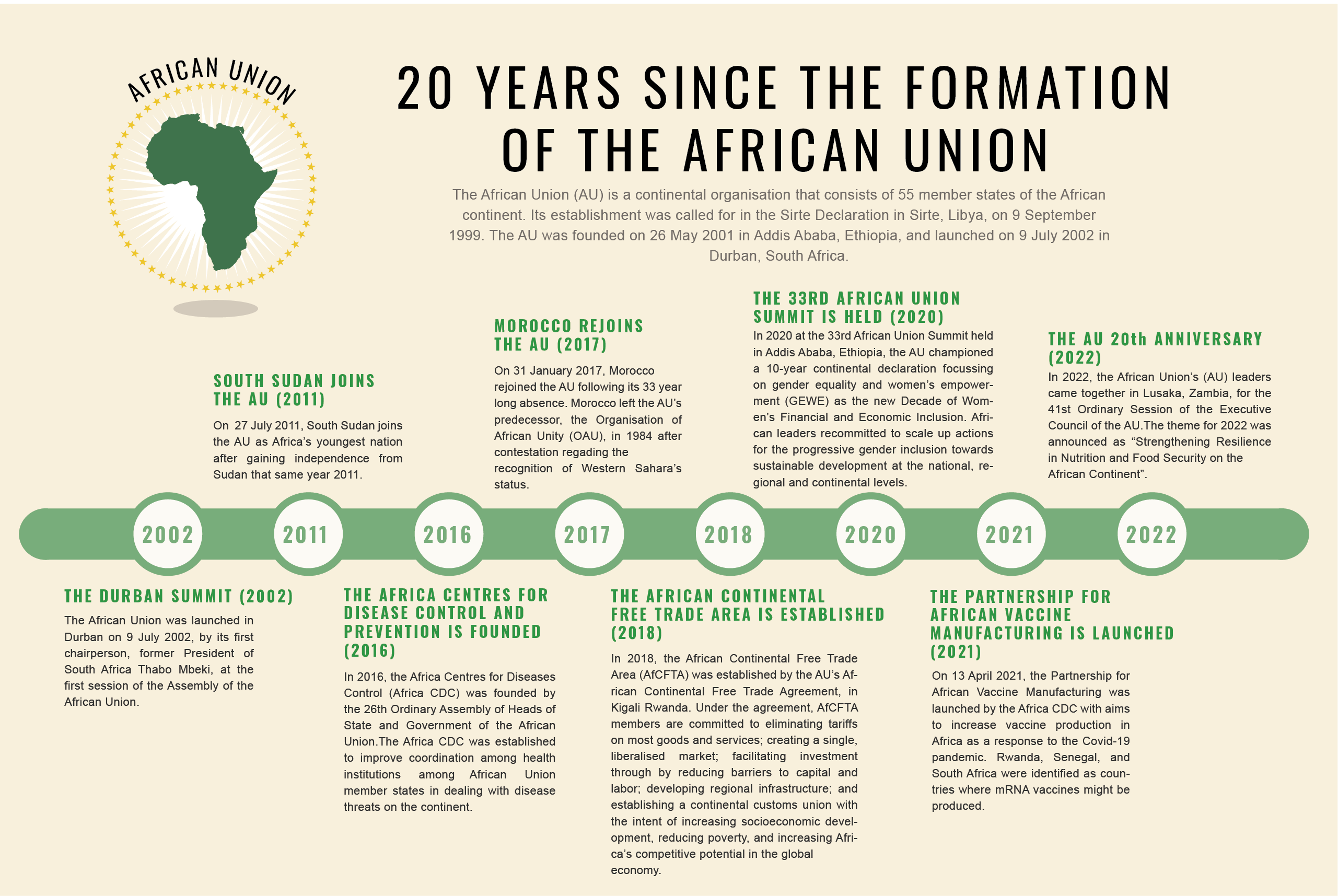

On 9 September 1999, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) adopted the Sirte Declaration calling for the establishment of the African Union (AU). The AU was officially launched on 9 July 2002 in Durban, South Africa. As former President Thabo Mbeki noted, when the AU was formed, “Africa was free from colonial and apartheid oppression, except for the persisting case of Western Sahara.” He went further by stating: “The fact that its inaugural conference was held in erstwhile apartheid South Africa emphasised the fact of this new reality on our continent.”

Graphic: Mischka Moosa

While the AU’s mission statement speaks of “an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena”, it was believed the AU would lead Africa into the future through the ideals of African renaissance and Pan Africanism. So, at the ripe age of 20, it may be an opportune time to take stock of achievements and missed opportunities towards meeting its core objectives. When examining the literature on AU’s achievements, it becomes clear that there is no shortage of criticism from a wide variety of commentators.

Below are some of the successes and challenges the AU has encountered over the last 20 years

Successes

- AU Constitutive Act of 2000

A key foundation pillar of the AU that differed considerably from its predecessor, the OAU Charter, was the AU Constitutive Act of 2000 allowing for interference in the internal affairs of its members to stem instability, halt egregious human rights abuses, and sanction military coups d’état.

- Agency

The AU has, since its launch, developed considerable agency to shape the agenda and decisions in Africa, and to actively participate in global affairs. The AU has helped Africa to develop into a regional bloc second only to the EU in its institutional development. This process has significantly strengthened Africa’s international agency, and Africa now speaks as one voice on a diverse range of issues for the benefit of African needs and priority areas, such as peace and security, infrastructure and energy, climate change, innovative development financing, training youth, and women’s empowerment.

Another example of African agency is Agenda 2063, presenting Africa’s vision for its growth and development over the next 50 years. This blueprint for Africa’s development and economic growth has been at the forefront of political dialogue between African countries and strategic international partners.

- COVID-19 pandemic response measures

Under the AU stewardship of President Cyril Ramaphosa, the Africa Centres for Disease Control (Africa CDC), the AU African Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT), and the AU’s vaccine delivery task team have been commended for their efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. According to recent Africa CDC data, Africa has received 945 million vaccines doses through various initiatives. To ensure widespread access to COVID-19 vaccines across Africa, the AU sought to achieve continental herd immunity by 2022, despite instances of vaccine nationalism taking place around the world, where wealthier countries have bought and hoarded vaccines, with little consideration for developing nations.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the AU has elevated the Africa CDC from a specialised technical institution to a public health agency with regional collaboration centres concentrating on strengthening Africa’s response measures to tackling future epidemics and supporting member states’ public health in general.

- African Continental Free Trade Area

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the world’s largest free trade area bringing together the 55 countries of the AU and eight Regional Economic Communities (RECs). The overall mandate of the AfCFTA is to create a single continental market with a population of about 1.3 billion people and a combined GDP of approximately US$ 3.4 trillion. The AfCFTA is one of the flagship projects of Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, the African Union’s long-term development strategy for transforming the continent into a global powerhouse eliminating trade barriers, and boosting intra-Africa trade. The success of the AfCTFA could potentially lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty.

The importance of regional integration cannot be exaggerated given the low proportion of inter-African trade when compared with other regions. The volume of trade among countries of the continent is around 15% of total trade, while in Europe, North America, and Latin America, rates are 68%, 37%, and 20% respectively.

- Decade of Women’s Economic Financial Inclusion

In February 2020, the AU championed a 10-year continental declaration focussing on gender equality and women’s empowerment. This declaration, called the Decade of Women’s Financial and Economic Inclusion, sees African leaders commit to acting for gender inclusion towards sustainable development at national, regional, and continental levels.

- Peace and Security

The AU has made some progress in peacekeeping across the continent by establishing the African Standby Force (ASF) in December 2003. The ASF is a continental multidisciplinary peacekeeping force, with military, police, and civilian contingents, that acts under the direction of the AU. The ASF is intended to be deployed in times of crisis in Africa. To ensure effective operation, the force is decentralised and coordinated at a regional level. It has been deployed in varying degrees to confront and manage insurgency-related conflicts in various countries.

Military regimes in Togo, Mauritania, Madagascar, Niger, Egypt, Sudan, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Burkina Faso were at various times suspended from the AU. In addition, the AU launched commendable military stabilisation missions to Burundi (2003), Darfur (2007), and Somalia (2007).

Setbacks/Missed opportunities

- Continued acts of unconstitutional changes of government

The AU has been accused of being slow to act on the actions of recent coup makers. This contrasts with its outspoken stance in previous years, ostracising military regimes in Guinea-Bissau and Sao Tome and Principe in 2003, Togo in 2005, Mauritania in 2005 and 2007, Guinea in 2008, Mali in 2012, as well as Egypt and the Central African Republic in 2013.

A reason for the recent resurgence of coup frequency may partly be explained as a consequence of the failure of democracy in Africa. There is a need for the AU to adopt more stringent resolutions aimed at addressing unconstitutional changes of governments, while continuously strengthening its promotion of democracy.

- Lack of engagement with civil society

The AU has also been criticised for its lack of consultation with member states’ civil society stakeholders. Engagement with civil society would lead to better accountability and provide a sense of ownership for the citizens of member states, while also bridging trust deficits.

- Funding challenges

The AU remains heavily dependent on external funding for its operations. An example, at the October 2021 Executive Council Meeting, Ministers approved an overall AU Commission budget for 2022 of just over US$650 million. This comprises US$176 million for operations, US$195 million for programmes, and US$279 million for peace support. International partners were expected to fund 66% of the budget and member states 31%. The remaining 3% was to come from the administrative and maintenance reserve funds. This is, however, far from the AU’s goal of self-financing its total regular budget and at least 75% of its programme budget, which is still fully funded by partners.

Way Forward

As the AU moves forward, one must remember that it has ably brought together its 55 member states to take common positions on many critical global issues such as building consensus on UN reforms, the COVID-19 response measures, and financing of African development initiatives.

However, despite these successes and Africa’s growing ability to generate and set its agenda, and its growing capacity to become increasingly assertive in formulating and promoting its positions, circumstances such as the inequitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines highlighted that Africa still struggles, at times, to transform this agency into direct benefits for its peoples.

While Africa may be burdened with many challenges, Africa still needs the AU because it plays a pivotal role in addressing the various challenges confronting the continent. While the AU can be criticised for some acts of inaction, it is also currently the only inclusive platform available to achieve “an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena”.

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.