Soldiers from Colonel Mamady Doumbouya’s team of special forces walk through a hotel during a meeting with high level representatives from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in Conakry on 17 September 2021. Colonel Doumbouya’s special forces seized Alpha Conde in a Coup on 5 September 2021. Photo: John Wessels/AFP

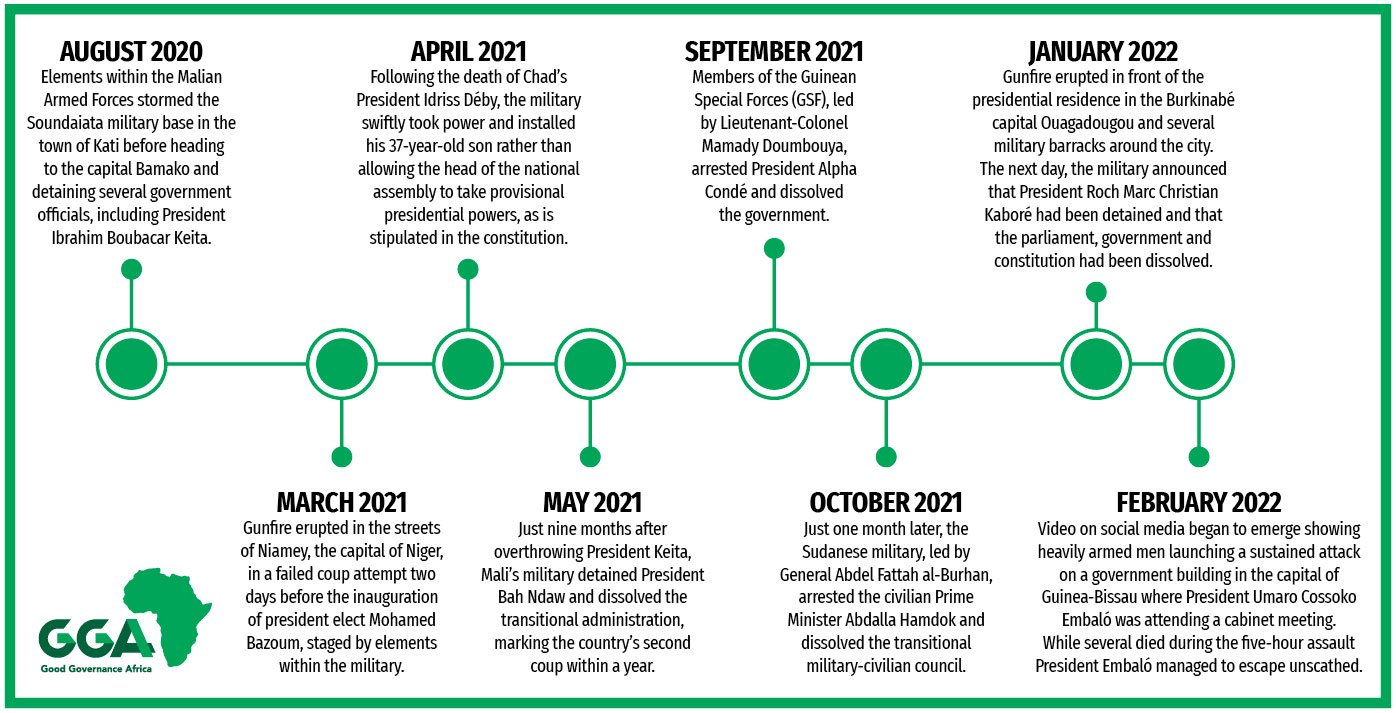

On 1 February 2022, just two weeks after the military ended the rule of President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré’s administration in Burkina Faso, an attempted coup took place in Guinea-Bissau. Videos on social media showed heavily armed men launching a sustained attack on a government building in the West African nation’s capital city where President Umaro Cissoko Embaló was attending a cabinet meeting, leaving scores dead.

The attempted coup was the latest in a wave of military takeovers across the Sahel and West Africa, which our national and regional governance institutions seem powerless to stop. It represents part of a profound crisis facing the continent and a deepening democratic recession.

‘To coup or not to coup – making sense of the changing nature of coups’ – Read more

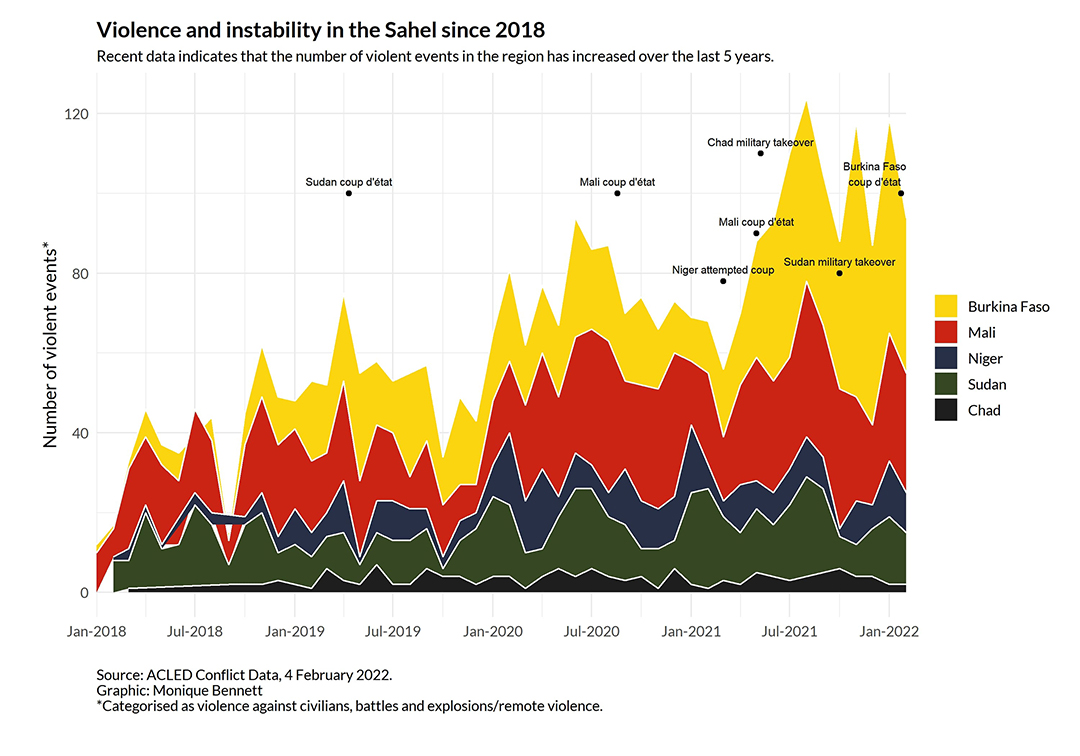

Guinea-Bissau’s failed coup marks the eighth attempted or executed military takeover in 18 months. A year after the African Union’s pledge to ‘silence the guns’ to create conditions conducive for sustainable development, they are louder than ever. The continent is now home to more than half of all state-based armed conflicts in the world; it has just experienced its bloodiest year since 2014, and has reversed a decades long decline in the annual number of coups and coup attempts. Sahelian states are facing political instability against a backdrop of increasing violence by extremist and non-state armed groups – one of several transnational security challenges which require regional coordination and collaboration to effectively address in the region.

As new crises emerge, the old crises go unresolved. Despite suspension from the AU and calls from the international community to restore the country to civilian rule, Burkina Faso’s military government appointed the coup leader, Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, as president. Mali’s military junta has remained intransigent in its stance to defer presidential elections in the face of sanctions imposed by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), while Prime Minister Hamdok remains under house arrest in Sudan and the country’s military refuses to bend to international calls for a return to constitutional order.

An arc of conflict and political instability now stretches 5000 kilometres, from Guinea on Africa’s West coast to Ethiopia on its East, negatively impacting upon the lives and prospects of tens of millions of Africans.

These events defy easy explanation. There are multiple factors to consider. However, what this moment should prompt is an unsparing interrogation of our institutions and systems of governance, at the national, regional, and continental level to determine whether they are capable of resolving disputes and creating inclusive political settlements on which a prosperous future can be built. Where these institutions and practices do not fit the local context or are the hold-over from a colonial past, they must be reimagined.

In the coming weeks, GGA will be publishing a series of analysis pieces on the critical issues to consider in light of the proliferation of military takeovers and political instability across the Sahel and West Africa.

Some of the issues which will be covered will include:

- An analysis of the major governance deficits within the region, including its historical dimensions, to determine why the institutions and practices are unable to effectively produce stability.

- A look at the primary drivers of fragility, including environmental, demographic, and economic factors which exert pressure on these societies and their governments.

- The historical and current role of foreign actors in the region, such as France, Russia, and the United States, and how their influence shapes the political and security landscape.

- The political economy dimension of instability, including the ‘resource curse’ and role of good natural resource governance in creating inclusive political settlements.

- The efficacy of regional and continental response by ECOWAS and the AU.

[activecampaign form=1 css=1]

Stephen Buchanan-Clarke is a security analyst with several years' experience working in both conflict and post-conflict settings in Africa, primarily on issues of peace and security; transitional justice and reconciliation; democratisation and governance; and preventing and countering violent extremism. He currently serves as head of the Human Security and Climate Change (HSCC) project at Good Governance Africa and is a co-editor of the Extremisms in Africa anthology series.