SDG 9: Innovation, infrastructure and sustainable development

Africa’s lack of infrastructure is becoming particularly noticeable in an era of technological innovation

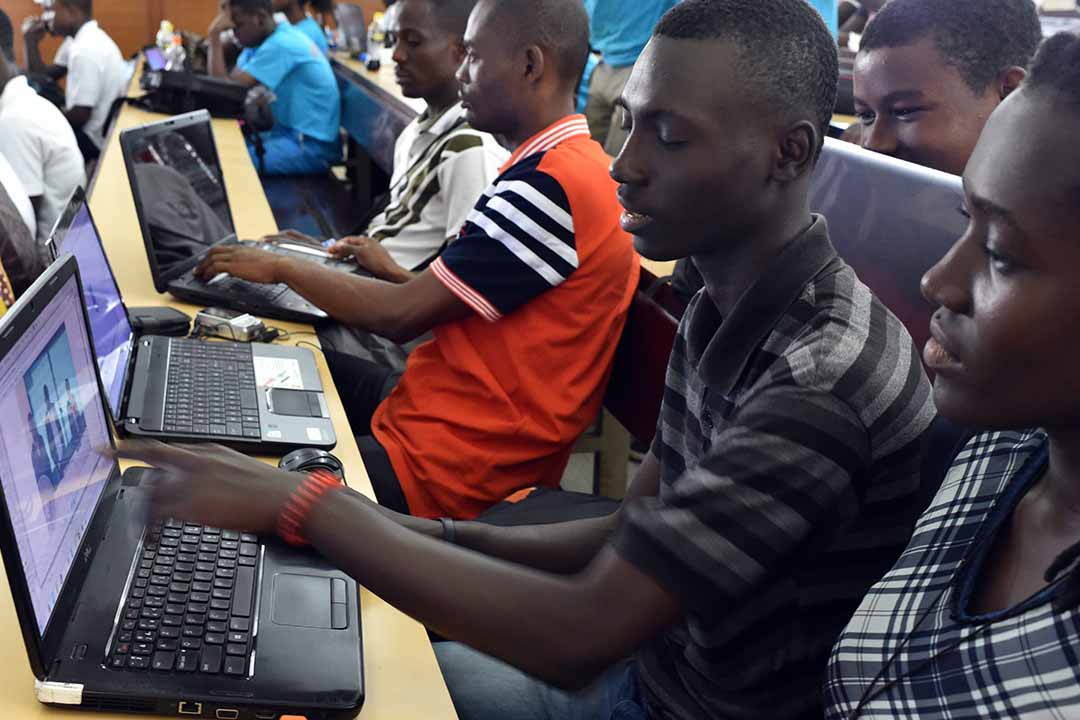

People attend a computer training course as part of the Africa Innovation, Reinvent Media programme at the Ecole Superieure Africaine des Technologies et des Communications in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Photo: ISSOUF SANOGO / AFP

By Yunus Momoniat

Even in 1972, when the term “sustainable development” was first used, there was an inkling that industrialisation – which is the only means of supplying the necessities of life to large populations – was a deeply destructive process. The word “pollution” was just beginning to enter our lexicon. In 1987, with the publication of a UN report, Our Common Future, the United Nations defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the future generation’s ability to meet their own needs”. The approach seeks to “balance different, often competing, needs against an awareness of environmental, social, and economic limitations”. SDG 9 (Innovation, infrastructure and sustainable development) sets a number of sub-goals that aim to “build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation, and foster innovation”. Key sub-goals include: increasing the number of those employed in manufacturing; increasing the proportion of GDP spent on research and development (R&D), as well as the number of researchers; supporting medium- and high-tech industries; and increasing development assistance for infrastructure. The UN measures advances in SDG 9 using various indicators, among them such factors as access to mobile phones and the internet, the number of scientific and technical journals published and the quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure. As regards the last indicator, the African picture is uneven, as is to be expected. South Africa and Kenya score well as far as roads and transport are concerned, with South Sudan scoring lowest. As regards the other indicators mentioned, Tunisia and South Africa have the most scientific journals in print, South Sudan the least. Meanwhile, São Tomé and Príncipe (87.7%) and Gabon (83.4%) have the highest percentages of mobile phone subscriptions, with Eritrea the lowest (though no figure is provided).

Development will always be an uneven process, replete with experiments that go wrong. No plan will be rolled out without setbacks and unintended consequences. If Africa is to have a chance at economic development, however, it will above all need to embrace new technologies that promote development while bypassing the smoke and fog of the first industrial revolution. In economic terms, the notion of “leapfrogging” denotes the idea that societies can sometimes jump to a stage of development without incurring the costs of earlier stages. In Africa, for example, the cell phone has made the ability to communicate available to African people who would otherwise not have had it due to poor development of telecommunications infrastructure. The role of the state in creating infrastructure cannot be underestimated, especially in the provision of roads, transport, education and sanitation, and governments must provide these services. But today’s state must also allow for forms of infrastructure that can be developed locally, that will bypass the trajectory of the developed world, where infrastructure came at the cost of environmental degradation. Solar technologies are one such example. Antonio Estache and Quentin Wodon, in their book Infrastructure and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa (2014), argue that the quality and size of a country’s economic performance is directly reflected in its infrastructural development: the larger a country ‘s infrastructure stock, the greater its GDP growth is likely to be. However, they add that until a decade ago the literature on growth largely ignored the role of infrastructure in economic development. Yet the institutions associated with infrastructure are crucial in promoting growth, especially if they increase competition. In addition, they point out, not investing in infrastructure results in significant costs for any society.

“Most Africans remain unconnected” to electricity grids, while “at least 30 [African] countries face regular power shortages,” according to Shirin Elahi and Jeremy de Beer in their book Knowledge and Innovation in Africa: Scenarios for the Future (2013). Moreover, the 10 countries where electricity is most costly are all African, they add. They also argue that “leapfrogging” will address these problems. “Africa has the opportunity to leapfrog to renewable energy provision – and “the resource blessing of ample solar and wind supplies, which come free,” they say, However, achieving these gains will require political will. Infrastructure has to have a degree of permanence, as Elahi and De Beer point out, for “unsustainable technologies ultimately exacerbate rather than solve challenges”. This is doubtless an important reason for the UN’s continued focus on resilience down the decades. “Sustainability” in this context suggests that infrastructure must also be maintained if it is to be resilient. Unfortunately, the maintenance of infrastructure has also seldom been a governmental priority in Africa. Estache and Wodon point out that for higher growth “the average annual infrastructure expenditures … would need to be around 15% of GDP”, which is “more than twice what Africa has spent on the infrastructure sectors” since the mid-1970s. They also say that between 2007 and 2012, about 80% of all private investment (US$9 billion) in infrastructure projects in Africa went to the telecom sector, while water and sanitation hardly got any. Moreover, most of the private money continues to be concentrated in some of the largest and most successful economies (such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda, and Kenya). Africa’s lack of infrastructure is becoming particularly noticeable in an era of technological innovation, which is an important driver of progress and development, and, by definition, the creation of new ways of doing things. The process of creating something new depends on research and development. In Africa, where governments struggle to raise revenues for adequate budgets, R&D is often way down on the lists of treasury ministers.

Quartz Africa’s annual list of 30 pioneers of innovation offers some examples. The 2018 list includes people from Nigeria (five), Kenya (four), South Africa (four), Uganda (two), Egypt (two), Ghana (two), and one each from Rwanda, Gambia, Senegal, Cameroon, Mali, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Congo, Ethiopia and Somalia. The survey reveals some unsurprising trends. Most of the innovators are from the continent’s more developed economies. Many have lived or studied in the developed world and returned to their home countries to develop and implement their innovative programmes. And – reflecting the likely importance of leapfrogging in Africa – most of their innovations have relied on new technologies. Moreover, innovation does not only involve scientific advancement. Planned economic changes can also be seen as forms of innovation. Similarly, infrastructure is not necessarily physical structures: it can just as well be the creation of an institution, or agreements between individuals, organisations, parties or states – trade blocs, for example. Moreover, innovation is inherently unpredictable, and “does not always bring positive outcomes”, as Elahi and De Beer emphasise. All of this supports the argument that notions of innovation used by the UN are far too technocratic, as advanced by Mario Scerri, a professor at South Africa’s Tshwane University of Technology and the author of a series of books on national innovation systems. He proposes a broader notion of innovation to replace that of the UN. Others have taken this up, and elaborated the idea of “grassroots innovation”, with a number of organisations adopting it in their approach to stimulating innovation. Practical Action, a group founded in 1966 by economist EF Schumacher and colleagues, is helping communities secure access to drinking water, sanitation and waste services, using solar-powered water pumps, rainwater harvesting and bio-latrines, among others.

In practical terms, “grassroots innovation” involves the insistence that innovation must result in social and material benefits, for example, the provision of electricity, an increasing crop yield, or averting pollution. The SDGs are not discrete projects, they intersect and crosscut: each goal depends on many of the others being achieved. But all are meant to help achieve Goals 1 and 2: to reduce and avert poverty and hunger. Given this, among the 17 goals two can be identified as perhaps the most important for innovative approaches to Africa’s challenges: agriculture and education. Africa must raise the level of its agricultural production if it is to produce enough food for its inhabitants, especially since the continent has fallen behind other regions, according to the late Calestous Juma, in his book The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa (2015). Africa is composed largely of agricultural economies, but farming is not as productive of food and livelihoods as in other regions. Yet African R&D in agriculture is lagging behind the rest of the world, said Juma. Sub-Saharan Africa has a particularly low level of spend on R&D, and farmers receive little support from investors, so they rarely invest in irrigation, fertilisers or technical inputs. They also fail to connect to export markets, growth being constrained by high marketing and transportation costs. Juma made a strong case for the linkages between agricultural and economic growth. A second imperative would be to improve the quality of education throughout the continent. The theme here is the interconnectedness of disciplines. Heila Lotz- Sisitka, Overson Shumba, Justin Lupele and Di Wilmot, the editors of Schooling for Sustainable Development (2017) argue that “learning processes involve engagement with matters of concern that arise at the socialecological- economic-political interface”. Seen from a sustainability point of view, “learning should be understood as a process of discovery that allows children in schools to participate in and generate a new understanding about themselves and the world around them.”

Authors of the various papers included in the book make a number of pertinent recommendations. Learning should be geared towards the future but also celebrate heritage. African experience must aim to make the sciences more intelligible. Schools should engage with their communities to create a consciousness of sustainable development. Learners should be empowered as active agents rather than passive receivers of knowledge. Learners should be taught to think critically and systemically. Curricula should be renewed to reflect the crises we are already facing. And teachers should be trained to teach about sustainable development. These are all noble goals, of course, but they can only be achieved if African states are well established, and their institutions functional. Moreover, their leaders will need to have the political will to implement programmes in a clean and efficient manner, free of corruption. States also have a duty to stimulate intellectual growth, and innovation. Historically, states have often been the source of the research and infrastructure that ultimately facilitate innovation, Scerri insists. A prime example is the internet, which was a product of the US military-industrial complex, but was further developed by university and private initiatives. But on a continent where many states are underdeveloped, lack reach and where officials are often corrupt, basic needs might have to be procured in ways that do not depend on a centralised authority. Decentralisation might be a value in itself. In some instances, indeed, this might require the state to step back, rather than to step in. Where states are incapable, for whatever reasons, they ought to recognise this. For example, African states would sometimes more effectively contribute to development by limiting or eliminating legislation and regulations that prevent ordinary citizens from experimenting with their own methods of provision. Yet, notoriously, they often don’t. Continent-wide state hostility to informal business is an example here.

Finally, the problems of Africa often cross borders and may not be amenable to sovereign tinkering, as the Ebola crisis in West Africa from 2013 to 2016 demonstrated. In the end, that health crisis required continental and international intervention. And if anything, the fact that Ebola has recently resurfaced in the DRC shows that regional cooperation on such matters is necessary. The realisation of the UN’s SDGs will depend on many factors, not least the role of governments as well as regional blocs, but also ordinary citizens in both urban and rural settings. Governments will have to learn when to step in – and out, while citizens must step in wherever they can, ensuring their leaders stick to their tasks. Governments must keep an eye out for opportunities to leapfrog, while citizens should be allowed to create innovations – and make mistakes. Reviewing all this, we see that SDG 9 represents an ambitious programme. The SDGs are, according to Thomas G. Weiss, an “indigestible menu of aspirations”. Writing in his book What’s Wrong with the United Nations and How to Fix It (2009), he points out that not all of the world’s countries will be able to meet their considerable developmental expectations. Moreover, as the articles in this edition of Africa in Fact illustrate, the expectations, formalised as the SDGs, can be difficult to measure and monitor, especially in Africa. Nevertheless, the SDG deadline does possess one enormous merit: it is focusing the efforts of governments, NGOs, activists and citizens on set targets, and a fixed date.

Yunus Momoniat is a researcher and writer at South African History Online and an occasional political commentator.