Review of The Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Recolonisation of Africa, The Coloniality of Data, by Everisto Benyera, Routledge, Oxford, 2021

Effusive predictions have been made about the benefits of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), with some commentators seeing it as a panacea for every ill suffered by society. Everisto Benyera disagrees, seeing the harvesting of data at the heart of the “revolution” as a sinister means to recolonise a continent long suffering from the effects of colonial and neo-colonial penetration.

Benyera asserts that Africa “will accrue minimum benefits and suffer maximum consequences in the 4IR”. Moreover, “the affluence of the Global North is funded by the poverty of the Global South”, and it is in their interests to keep Africa in the virtual chains of 4IR.

He also asks why Africa remains in a state of poverty and underdevelopment even though colonialism officially ended when most states were granted independence in the 1960s. Colonialism’s supposed end did not bring the promised land, and Benyera regards decolonisation as one of the great myths of our time, arguing that it effectively didn’t take place, and that relations of domination, oppression and economic subservience have never been dissolved.

The West, Benyera argues, – he refers to it as Euro-North America – would perish if it was unable to draw on the resources of Africa, and it is in the bloc’s interest to keep the continent powerless and enslaved so it can continue to thrive. “The centre dispenses hell in the (former) colonies in order to deliver heaven to itself,” he writes.

Thus, France continues to intervene and meddle in the affairs of its former colonies, while Britain keeps tabs on its former realm through the Commonwealth.

He considers the US as the most vigorous of the colonial powers, with its African Command (Africom) having a presence in scores of countries throughout the continent. It is currently using the fight against Boko Haram to consolidate its hold on vast regions. Barack Obama’s summit with African leaders in 2014, Benyera declares, amounted to a second scramble for the continent.

Benyera includes China in the list of neo-colonial powers, since it draws vast amounts of raw materials from the continent, exercising control over countries by keeping them debt-ridden. He is scathing about the role African leaders play, in effect mere proxies for the great powers, ensuring the latter can extract what they need. He sees Rwanda’s president, Paul Kagame, as a particularly sinister force. He claims Kagame is the real power behind the DRC, which has an abundance of the minerals needed for new technologies such as cell phones.

Benyera sees it as no coincidence that the most violent wars occur where valuable resources are to be found – diamonds, coltan, oil, whatever is needed by the global economy. “Mineral-rich African countries are deliberately being destabilised by powerful cartels from the empire so that these cartels and their local collaborators can loot and recolonise Africa.”

Thus, the continent is in the grip of a capitalism that operates a “destructive extractivism”. Accumulation by the West is a process that is achieved by dispossessing the African: “Force, fraud, oppression, alienation, obfuscation, trickery, and misrepresentation are some of the methods used during accumulation through dispossession.”

Benyera coins the term coloniality to differentiate what happens in this period from the colonialism of earlier periods. He defines human rights as “living, and dying a dignified life devoid of humiliation”, but under coloniality, “human rights are a farce, decolonisation a myth, and (re)colonisation a reality”.

“Colonialism occurred in three distinct stages. The first one was the usurping of Africa’s political sovereignty. The second stage was economic enslavement, and the final stage was epistemological subjugation.”

According to Benyera, the first industrial revolution extracted raw materials and used slavery to enable the progress made in the US and elsewhere. The second industrial revolution brought colonisation and direct rule, and the process of extraction was made easier. The third industrial revolution brought an end to state sovereignty. The fourth industrial revolution portends a disastrous state of affairs.

The central thesis of the book is that the fourth industrial revolution will lead to the recolonisation of Africa. Multinational corporates will mine the continent for data and use it to control vast populations. Data, he declares, is “the latest weapon of mass destruction”.

The 4IR uses cloud computing, the Internet of Things and big data analytics to reign over the globe. It allows for connections between every sphere of life, bringing these under its control, allowing for businesses in Africa to be supplanted by corporations from Euro-North America. It extends its reach into government agencies, monitoring the activities of populations, through pharmaceutical research and development, statistical collections and algorithms.

The central mechanisms for this control are the cell phone and the computer: the former always involves the use of apps that depend on the acceptance of certain terms and conditions, which allow data companies to track users, rendering our private information as raw material for use in advertising and sales, providing statistics which make for super-efficient marketing through algorithms. “Data users are enslaved before using any app or downloading anything; they are given only one option, which is to agree to the terms and conditions.”

Data effectively belongs to those who harvest and store it, and not to us users of phones and laptops. Thus, 4IR also enables big tech to manipulate currencies and financial flows, and even political processes such as elections. Benyera cites the Cambridge Analytica saga and Facebook’s use of data for “political manipulation”. He concludes that “social media is nothing more than a global mass surveillance programme” and will result in a move to cryptocurrencies and the diminishing of sovereignty in Africa.

“Key casualties will be democracy, human rights, and development. The 4IR will see more unemployment and unemployability, inequality, poverty, and violence among the weak and the vulnerable.”

Benyera is convinced that slavery was never effectively abolished and is now being transformed into a digital phenomenon. “Africa will be part of these virtual and online communities not as an equal partner, but as an enslaved supplier of raw data.”

He paints a picture of surveillance capitalism, which monitors us when we are online, collecting our data and manipulating our desires. “The idea is to produce a human who is predictable, compliant, and responsive to online demands. This is intended to benefit capitalism as much as possible by deriving profit from as little advertising and marketing effort as possible.”

In his darkest passages, he talks of 4IR leading to humans implanted with computer chips that will enable direct control. “The fourth industrial revolution is going to be fronted by two phenomena; electronic persons, humanoids, robo-humans, and post-humans on one hand and big data on the other hand.”

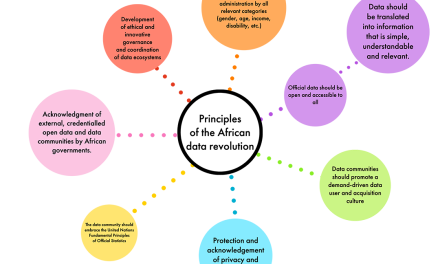

Benyera proposes that data centres dealing with African online users be based on the continent, and that legislation bring these under the control of local companies, to achieve what he terms data sovereignty.

He also proposes that users charge big tech corporates such as Facebook and Alibaba for the use of their data. This “digital right” must be added to the notion of human rights, in a world divided into the digitally privileged and the digitally deprived. He proposes a reinvention of African nationalism shorn of the excesses of post-independence elites.

But whether these measures will allow us to escape this coming dystopia remains to be seen. Benyera’s book is heavy with repetition, assertion and often inadequate expositions. It fails to satisfactorily explain many of its central arguments, but its overall message is not unconvincing, and it paints a frightening picture of our future on the continent. Let’s hope he is wrong.

[activecampaign form=1]

Yunus Momoniat is a researcher and writer at South African History Online and an occasional political commentator.