SDG 10: Reducing inequality

Reducing inequalities between rich and poor will not be easy, but it is vital for ensuring the continent’s stability and development

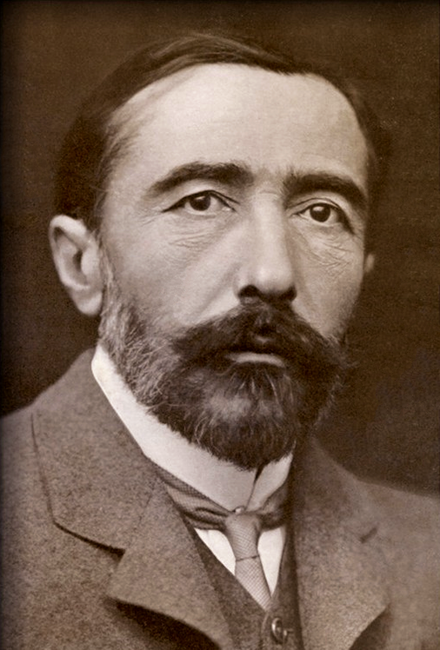

The makeshift shanty town of Makoko, built on stilts on Lagos Lagoon, is a stark demonstration of the extreme poverty divide between rich and poor in Nigeria’s commercial capital. Photo: PIUS UTOMI EKPEI / AFP

By Ernest Harsch

For many Africans on the lower rungs of society, greater social and economic equality would not only help improve their economic and social prospects; it would also open the door to exercising fuller citizenship rights. And, as more people across the continent realise the links between political oppression and social inequality, they are responding with action. This April, hundreds of thousands poured onto the streets of Sudan and Algeria to topple long-entrenched authoritarian rulers, motivated in part by anger over their difficult living conditions, set against the ostentation and blatant corruption of the governing elites. In South Africa’s impoverished black townships, “service delivery” protests are almost daily occurrences, in a country that is among the most unequal in the world. In northern Nigeria, “unemployment, widened inequality [and] hunger” are driving local discontent, notes Dr Muhammad Baffa Sani of Bayero University in Kano. In desperation, a number of youths have joined the notorious Boko Haram terrorist group. Some African leaders, beholden to wealthy and powerful cliques, simply ignore the problem. More of their compatriots, however, are starting to recognise the potential dangers. Boko Haram, for example, faces a “stark choice”, President Cyril Ramaphosa acknowledged in a state of the nation address in February this year, “entrenching inequality or creating shared prosperity”. African governments that are struggling to find the right policies and financial means to reduce inequality are now getting some support from the world community, which has pledged, as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to help reduce inequalities within and among countries. The latter part of that goal – narrowing the disparities between developing and developed nations – has long been part of the agenda of the UN and other international organisations. But addressing inequalities within countries has only recently received much official attention.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the main international financial institutions argued that the solution to African poverty lay in widespread liberalisation, to stimulate economic growth. Some economies did subsequently achieve higher growth, but often with continued – or even worse – poverty, due to liberalisation excesses and slashed social programmes. In 2000, as the tide of thinking then shifted towards concepts of “human development”, the international community adopted the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which highlighted dedicated anti-poverty measures and improvements in social wellbeing. Around the world, millions of people rose out of poverty. Yet according to the UN, as of 2013 nearly half of all people in sub-Saharan Africa still lived on less than $1.90 per day, the international poverty line. Moreover, poverty has proved especially persistent in countries with high income inequality. “Inequality does matter,” argues Arjan de Haan, a social development adviser with the UK’s Department for International Development. “Inequality – particularly in assets and gender – can even reduce rates of growth, hence indirectly limiting poverty reduction.” Conversely, numerous studies have shown that the benefits of growth reach wider sectors of the population in countries with less inequality. Such greater understanding of the role of inequality then influenced the negotiations for the SDGs in 2015. Aside from a range of targets for ending hunger, improving health and education, protecting the environment, strengthening governance, and other goals, the SDGs call for ending poverty (SDG 1) and for reducing inequalities (SDG 10). Based on various measures of income inequality, Africa is considered the second most inequitable region in the world, after Latin America. The contrasts can be striking. The Brookings Institute, a US think tank, reports that the number of African millionaires (measured in US dollar terms) doubled to 160,000 between 2000 and 2015. Meanwhile, between 1996 and 2011, the number of Africans living in poverty grew from 358 million to 415 million.

To measure progress in reducing the gap, one of the targets of SDG 10 projects raising the income growth of the bottom 40% of the population at a rate higher than that of the overall population. According to the UN’s SDG tracker (https://sdg-tracker.org/ inequality), many countries in Latin America and Asia have recently shown improvement in that indicator. But there is too little data on Africa to draw clear conclusions. Of the dozen African countries for which data is available, eight show a higher growth rate for the bottom 40%, with Burkina Faso and Namibia in the lead. Four register lower growth rates, with South Africa and Uganda the worst performers. In 2018, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) released a major study, Income Inequality Trends in sub-Saharan Africa, which included somewhat more comprehensive data drawing on household consumption surveys. Focusing on 29 sub- Saharan countries accounting for 80% of the region’s population, it reported that 17 managed to reduce their degree of income inequality between 1991 and 2011. The remaining dozen, however, registered an increase in inequality over the same period. The report noted some structural factors that contributed to those trends. Countries with higher – and rising – inequality are mainly in southern and central Africa. They have capital-intensive oil and mining sectors with limited employment, or are former settler societies that still have concentrations of large landholdings and other assets. Countries with declining inequality, mostly in West Africa, generally started out with lower levels of inequality and have predominantly smallholder agricultural sectors in which many people benefit from even modest improvements in productivity. At a public rally in March on the anniversary of Namibia’s independence from South Africa, President Hage Geingob cited his government’s anti-poverty commitment.

He said that some 400,000 Namibians were lifted out of poverty between 1994 and 2010, and more would be with wider use of targeted social safety nets, old age pensions and social grants for orphans, vulnerable children and people living with disabilities. He added, however, that “income inequality remains a problem” – in part because it is a remnant of the discriminatory legacy of apartheid rule. South African authorities also often cite the legacy of apartheid, which kept non-whites in segregated urban and rural enclaves, consigned them to the lowest paying jobs and deprived many of access to decent schooling and health care. The political side of that system ended 25 years ago. Nearly 2.3 million South Africans subsequently rose above the poverty line between 2006 and 2015, according to a recent World Bank study. Yet household consumption data from a 2014/15 Living Conditions Survey indicated that inequality has increased since 1994. “While still an important factor, the impact of race falls consistently across time in its contribution to inequality,” observed the World Bank study. Besides continued disparities in asset ownership, the report added that the stark divide in South Africa’s labour market was a major factor in promoting inequality, with many jobless and low-paid, unskilled workers at the bottom and only a few highly skilled earners at the top. President Ramaphosa has acknowledged governance factors as well, declaring that efforts against poverty and inequality “will achieve little unless we tackle state capture and corruption”. (In South Africa, the term “state capture” means, broadly, the dominance of patronage politics and so-called “grand” corruption over state institutions.) Across Africa, there are several other common shortcomings that contribute to inequality.

In some countries, the political or economic dominance of certain ethnic groups has left other groups at a severe disadvantage in gaining access to jobs, markets and assets – or to the quality education that very often helps families at the bottom improve their prospects. In every country, women have lower-paying jobs, fewer land rights, and less access to credit, education, health care and political power. Many different factors influence inequality, and they interact in complex ways. “There is no one ‘silver bullet’ to address [this] challenge,” observes Abdoulaye Mar Dieye, director of UNDP’s Africa bureau. “Multiple responses are required.” Among those responses, he suggests, should be: increasing the productivity of small-scale farmers; reversing urban favouritism in services and economic opportunities; promoting labour-intensive industries; setting minimum wages; and expanding social protection programmes. Analysis by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation shows that if African women farmers had equal access to land, seed, fertiliser and machinery, their productivity could increase by 20-30%, in turn helping to lift 180 million people out of hunger. Tax systems in many African countries are highly unfavourable to the poor. Everyone pays the same amount when customs and value added taxes are levied on consumer goods, although poor people can afford them much less than the rich. The wealthy, moreover, are often better able to evade paying what they owe by hiding some of their wealth or bribing tax officials. To achieve greater tax equity in Kenya, Leonard Wanyama, coordinator of the East Africa Tax and Governance Network, a civil society group, has urged the authorities to crack down on tax evaders and lessen the use of “regressive taxation that burdens the poor”.

In health, experts argue, governments should allocate greater funding to local community clinics, which generally cater to the poor, instead of favouring the urban hospitals that mainly serve those who are better off. They also recommend reducing or eliminating “user fees”, which hit poor people disproportionately. When Uganda abolished user fees in 2001, visits to health facilities increased by 80%, with half that increase coming from the poorest fifth of the population. Deciding on the most appropriate mix of policies should ideally involve direct consultations with local communities. “Kenyans living the realities of inequality… understand the problems,” Njoki Njehu, Africa coordinator for the Fight Inequality Alliance, an international activist network, told Inter Press Service. “The solutions start with us.”

Ernest Harsch is a journalist and academic who has focused on African political and development issues since the 1970s. He has published several books, most recently Burkina Faso: A History of Power, Protest and Revolution (London: Zed Books, 2017), and is a research scholar at the Institute of African Studies at Columbia University in New York.