Towards the end of last year, President Cyril Ramaphosa overcame his most difficult political battles. The parliamentary section 89 report on the money stolen from his Phala Phala farm that could have led to an impeachment process was set aside and he was re-elected as president of the ANC at the party’s 55th national conference in December.

Switch up: President Cyril Ramaphosa is likely to make changes to policy and to the executive branch of the government. Photo: Rajesh Jantilal/AFP

His victory places him at the apex of political office, both in the ANC and as head of the state. In the recent past, ANC presidents have had a hard time concluding their second terms. Neither Thabo Mbeki nor Jacob Zuma finished their second terms. If Ramaphosa can consolidate the new national executive committee (NEC) and the yet-to-be-elected national working committee and stay clear of corruption allegations, he might see his second five-year term to completion.

He is likely to make several changes not only in terms of policy but also regarding the composition of people he will appoint to govern alongside. Since Ramaphosa won’t be up for re-election at the 56th ANC national conference, he may choose to seize the opportunity of focusing on implementing meaningful policies in government.

After the 55th national conference, at which Paul Mashatile was elected as deputy president, there has been a growing expectation of a cabinet reshuffle. Mashatile’s victory has left the incumbent deputy president David Mabuza’s position uncertain.

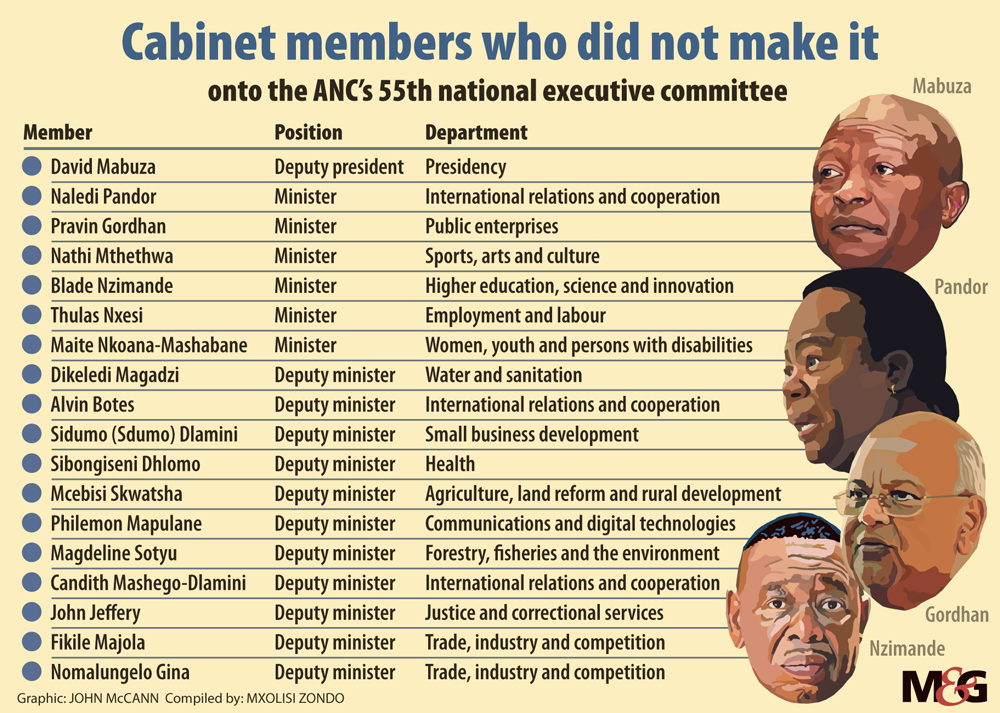

Alongside Mabuza are several other ministers and deputy ministers, which include Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan, Employment and Labour Minister Thulas Nxesi, International Relations and Cooperation Minister Naledi Pandor, and Sports, Arts and Culture Minister Nathi Mthethwa, who were not elected into the party’s NEC.

Key departments such as the Department of International Relations and Cooperation and the Department of Trade and Industry have more than one minister who did not make it into the NEC. Although serving in the NEC is not a requirement to be appointed to the cabinet, Ramaphosa will have to think long and hard about what he wants to do with these cabinet members.

He will also have to keep in mind growing calls for change in the substance of the country’s political leadership, which would introduce a more efficient and competent executive. South Africans are simply tired of an indecisive and directionless government that is incapable of addressing the country’s critical issues of unemployment, inequality and poverty and failing to drive its own development agenda set out in the country’s National Development Plan Vision 2030.

Delivering the ANC’s January 8 statement, Ramaphosa declared 2023 as “the year of decisive action to advance the people’s interests and renew our movement”. To realise this, he will need to appoint cabinet members who are capable of addressing South Africa’s socioeconomic problems.

He will also need to decisively deal with those who have not delivered on the party’s mandate and have not advanced the people’s interests.

The moment calls for Ramaphosa to be cutthroat in selecting a fitting A-team to do the job. He has an opportunity to lead an NEC and cabinet that shares a development vision and is capable and ready to lead. As such, the new cabinet could be one that truly serves the people, led by a leadership that will prioritise service delivery and good governance. The ball is in the president’s court.

The cabinet reshuffle comes as the country is experiencing stage six blackouts as implemented by Eskom. These blackouts have served as nothing but a disruption to the country’s economy and an introduction of a “new normal”.

On 12 January, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa announced the approval of an 18.65% electricity tariff increase effective from April 2023.

The hike is harmful to consumers who are already struggling with the price of electricity (and rising food costs) and imposes an additional constraint on businesses that are still recovering from the economic effects of Covid-19, along with the general economic difficulties.

Additionally, the expected high cost of electricity as of April is likely to result in negative revenue collection for municipalities, especially in those that are already struggling with illegal connections and financial arrears.

The Eskom situation must be one of the most important considerations when Ramaphosa appoints his new cabinet. If the power utility is to remain in the public enterprises department, the ministry needs a leadership with the political will to create an environment of transparency and accountability.

Leading up to the cabinet reshuffle, Ramaphosa has some difficult choices to make: whether to keep Gordhan as the public enterprises minister, considering the problems state-owned enterprises have had under his leadership and his absence from the NEC. Ramaphosa also needs to decide whether a separate energy ministry is necessary to better address South Africa’s energy needs but this may be problematic in light of an already bloated public service.

The ruling ANC has also taken a knock in the polls because of its poor performance in governing the country. Regaining public confidence will require more tangible solutions to Eskom’s woes than mere 11th-hour politicking by the ANC.

With mounting economic difficulties across the board such as slow growth, interest rate hikes, increased consumer price inflation and perpetual load-shedding, these calls may morph into criticism expressed at the ballot box if Ramaphosa chooses a cabinet that South Africans do not believe can address these problems.

The president’s selection of who he chooses to govern with him leading up to the 2024 general elections will not only define the fate of the ANC but also that of the country.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian on 27 January 2023.

Mxolisi Zondo is a Researcher in the Governance Delivery and Impact programme at Good Governance Africa. He holds a BA Honours in International Relations and a Bachelor of Political Science from the University of Pretoria (UP). He is currently pursuing his Master of Arts Degree in Diplomatic Studies at UP. His dissertation looks at the extent to which South Africa’s involvement in peace missions on the African continent serves the country’s national interest. Before joining Good Governance Africa, he worked as a Public Policy Intern at Frontline Africa Advisory. He has also worked as an Assistant Lecturer and Research Assistant at the University of Pretoria.