The 2022 Census report paints a gloomy picture of the development of post-apartheid South Africa. This is notwithstanding the undercount of the current latest Census report; 30% of homes and 31% of individuals were not part of the overall data sample.

This suggests that a significant number of South Africans and households were not reached due to myriad issues that may have led to limited access. Nevertheless, South Africa’s census data is essential for research analysis, forecasting, and policymaking. If the findings are any indication, South Africa has made some progress towards its development goals, but there is still a long way to go.

Unemployment and women’s empowerment

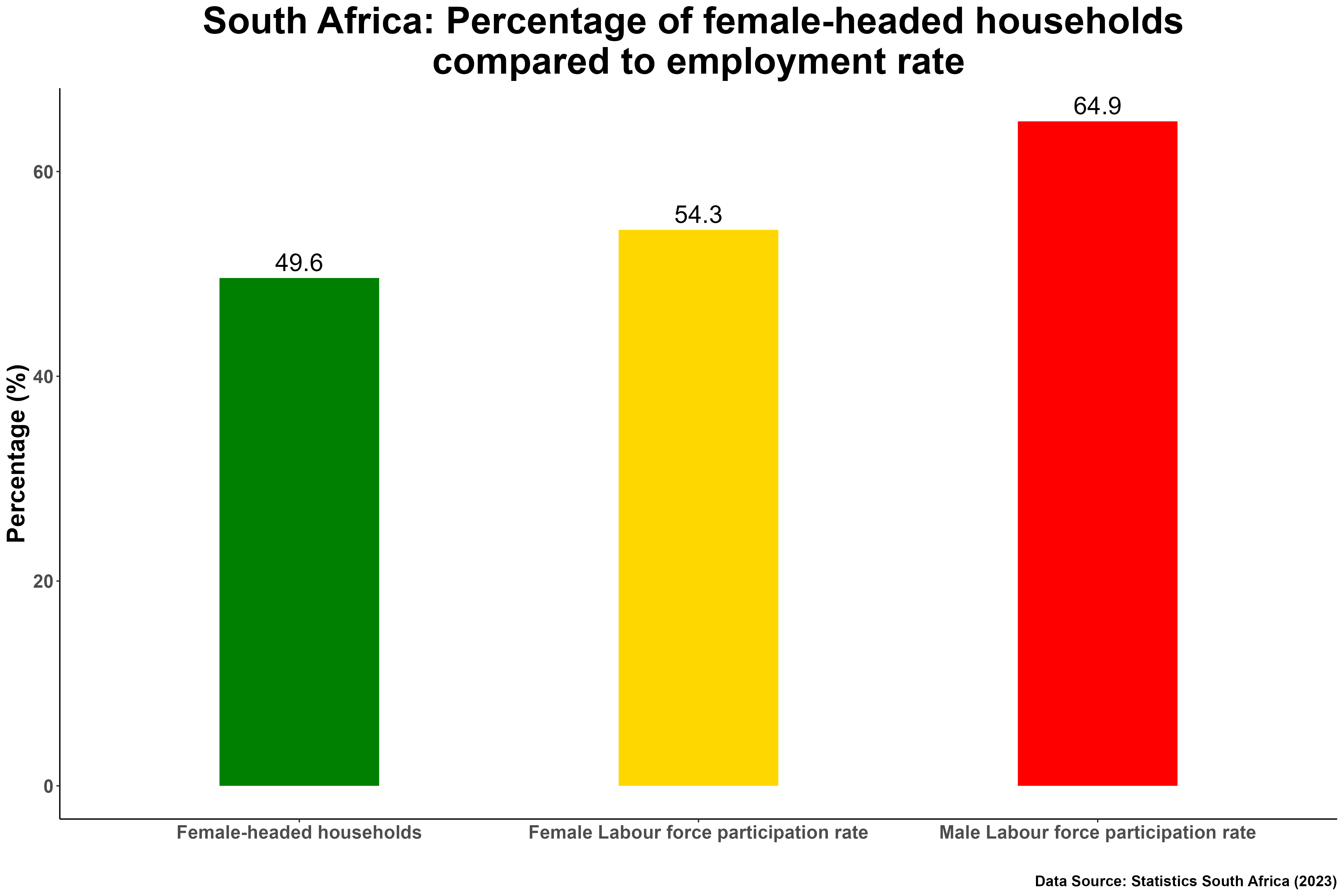

According to the Census, women headed more than 42.2% of all South African households. Households are essentially defined as homes that share resources. Therefore, for a better understanding of the implications of 42.2% of all households being headed by women, the figure must be juxtaposed against the number of employed women in South Africa. The labour force participation rate for women was 54.3% in the second quarter of 2023, while the rate for males was 64.9%, a difference of 10,6 percentage points, according to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey produced by StatsSA.

As far back as 2011, the National Planning Commission, whose Deputy Chairperson was the current President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, identified that young people and women are excluded from opportunities that would lead them to live the lives they would like. Even then, women comprised the largest percentage of poor individuals in South Africa. Accordingly, the National Development Plan (NDP) envisioned the upliftment of women in society, with a particular focus on education, employment, and overall economic participation.

Twelve years later, women’s participation in the labour force is 54.3% compared to 64.9% of their male counterparts. This gloomy picture worsens when considering the NDP’s vision of reducing unemployment to 6% by 2030. According to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS), South Africa’s unemployment rate had decreased by 0.3% in Q2:2023. In the expanded definition of unemployment, the current percentage of unemployed South Africans is 42.1%, with the official percentage also dropping by 0.3% to a total of 32,6%. This is just seven years away from the achievement of the NDP’s Vision 2030.

Where is the employment social compact?

The latest census should remind South Africa’s social partners, such as government, organised labour, organised business and community organisations as represented in the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac), to finalise the social compact that President Ramaphosa announced in his 2022 State of the Nation Address. As it were, this social compact would mark an attempt between the government and its social partners to formulate a comprehensive social compact to address issues of slow or zero economic growth and rising unemployment.

The goal of bringing South Africa’s unemployment rate down to about 6% by 2030 could only have been accomplished with coordinated efforts and shared commitment from the public and commercial sectors, labour unions, and communities. Social partners represented in Nedlac play a significant role in fostering legislative and policy proposals that promote economic growth, develop strategies for employment opportunities, and maintain a healthy labour market. As an example and refresher, just in 2020, Minister Pravin Gordhan signed an Eskom social compact.

What appears to be a significant reduction in load-shedding and an increase in South Africa’s electricity availability factor may be at least partly attributed to the Eskom compact, along with the strides that have been made by the recently appointed Minister of Electricity, Kgosientso Ramokgopa. This reference is made to indicate that social compacts have always been and continue to be effective in South Africa. Therefore, recognising social partners’ collective responsibility is necessary for tackling South Africa’s socioeconomic problems.

Education remains critical for skills development and wider economic participation

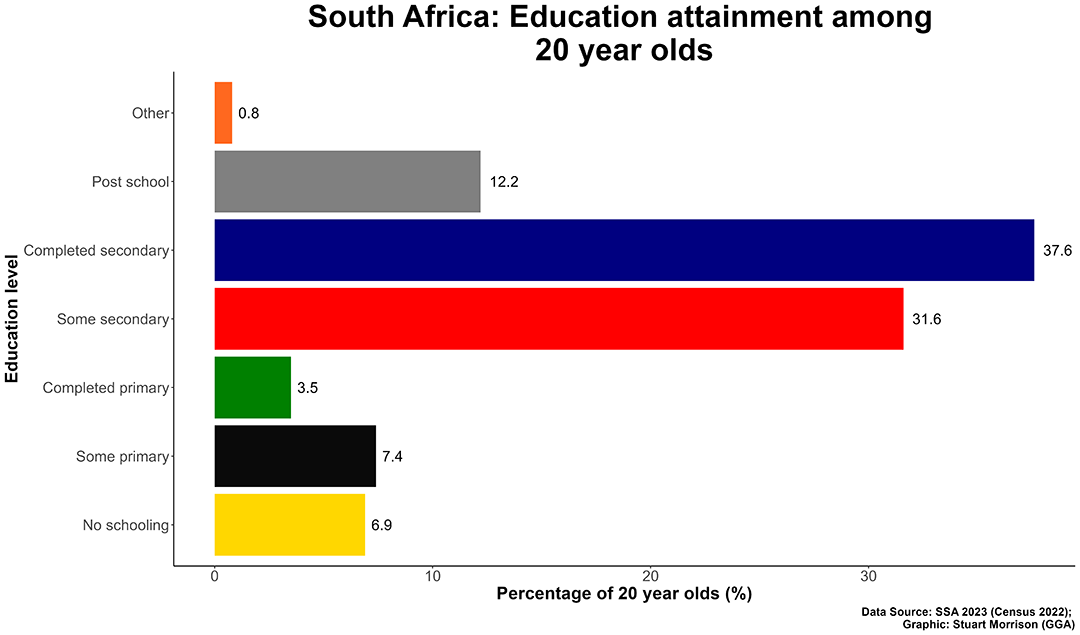

In 2011, the NDP also noted that the majority of black children receive subpar education, if any education at all—particularly higher education and training. Consequently, this contributed to keeping many South Africans from being able to find work in an already challenged economy. Additionally, it limits the potential vibrancy of South African businesses and lowers the earning potential and career mobility of individuals who manage to land employment. The 2022 Census report states that:

“Almost one-third (31,8%) of individuals aged five years and older attended some kind of educational institution. Nationally, 86.8% of these individuals attended primary or secondary schools, while a further 5.8% attended tertiary institutions. Only 2,1% of individuals attended Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges.”

The numbers presented by the census report show that while there may be a higher intake of learners at the level of early childhood development and basic education, the numbers drop significantly when it comes to higher education and training enrolments and, ultimately, graduations.

While the overall concerns about higher education are significant, it is also worth noting that what was highlighted by the NDP Vision 2030 concerning black children and higher education may be progressing in the right direction.

In this regard, the 2022 census report highlights that in 2022, black African students made up 76.4% of all students, which marks an overall increase from 60.2% in 2002.

While the above is appreciated, the overall number of students remains low due to the gradual drop in children’s education careers from early childhood development to high school. Ultimately, this contributes to the apparent lack of an inclusive, skilled and vibrant labour force in the country.

The South African government needs to emphasise basic education, understand the trends that lead to dropouts at the basic education level, invest more resources in dealing with this problem, and ultimately enrol more students in higher education and training.

As the problems at the level of basic education are addressed, this should be accompanied by a deliberate skills revolution that will reconfigure the higher education and training sectors. Understanding the potential contribution of TVET institutions as providers of skilled labourers is necessary in this regard. This would require marking TVET institutions as institutions of choice in the sector, where they are understood as skill-driven institutions and not institutions to turn to when universities reject students.

This must be combined with actively creating a labour-absorbing economy and enhancing proper governance mechanisms to help prevent and deal with corruption that always negatively impacts the poor and limits their access to education and training, ultimately negatively impacting the fabric of the labour force and cohesion between key social partners.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian.

Mxolisi Zondo is a Researcher in the Governance Delivery and Impact programme at Good Governance Africa. He holds a BA Honours in International Relations and a Bachelor of Political Science from the University of Pretoria (UP). He is currently pursuing his Master of Arts Degree in Diplomatic Studies at UP. His dissertation looks at the extent to which South Africa’s involvement in peace missions on the African continent serves the country’s national interest. Before joining Good Governance Africa, he worked as a Public Policy Intern at Frontline Africa Advisory. He has also worked as an Assistant Lecturer and Research Assistant at the University of Pretoria.