The coffin of African National Congress ( ANC) ward 103 Councillor Minenhle Mkhize in Richmond township, 90 kilometres west of Durban, on 29 January 2022. Mkhize was gunned down in a hail of bullets on 22 January. KZN province has been the epicentre of a recent spike in political killings. Photo: Rajesh JANTILAL/AFP.

South Africa has a history of political violence, including a culture of violent protests and political killings. Historically, the violence is rooted in diverse drivers such as ethnic and tribal differences, and political intolerance. These drivers were fuelled by the ‘Third Force’ of the apartheid regime’s security apparatus, which fuelled the inter-party rivalry between the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). As a result, thousands of lives were lost in the KwaZulu-Natal province (KZN) and parts of Gauteng between the late 1980s before the transition to democracy. More lives were lost in the early 1990s, during and after the first national democratic election.

Political violence is still very much part of the country’s political culture and creates a climate of insecurity, even if it is not on the same scale as in the early 1990s. At the most local level of government, it takes place in various shapes and forms, including scuffles in council chambers, as seen in the Johannesburg and Tshwane Metros in the last few weeks. Political violence is also witnessed in the often violent form of protests and looting, as was seen more vividly in the July 2021 unrest.

Increasingly, it manifests through threats, attempted political killings, and actual assassinations. Moreover, political violence breeds a climate of fear and a culture of intimidation. In 2017, for example, prominent ANC Youth League leader and Umzimkhulu Local Municipality councillor, Sindiso Magaqa, was killed for blowing the whistle on rampant procurement corruption in the municipality. This case, like many others, remains unsolved to date. Worryingly, political killings have been rising in both frequency and intensity, thus highlighting the need to interrogate the root causes of the problem. In the last few weeks:

- On 22 January 2022 – ANC eThekwini Metro ward councillor Minenhle Mkhize was shot dead outside his home in KZN.

- On 29 January 2022 – IFP councillor, the speaker of the Amajuba District Municipality, Reginald Bhekumndeni Ndima, 58, was shot and killed outside his home in Newcastle in KZN.

- On 13 February 2022 – ANC Nelson Mandela Bay Metro councillor Mzwandile “Zwelandile” Booi was shot dead in his vehicle at Kwazakhele in the Eastern Cape.

- On 26 February 2022 – ANC councillor in the Umvoti Local Municipality, Thembinkosi Lombo, was shot dead while walking to a food outlet in KZN.

Political killings mainly target individuals holding political and occasionally administrative positions in government. Presently, they are concentrated in the local municipal landscape, and primarily involve municipal councillors, who have been the target of more than 90% of all political assassination attempts in the past two decades.

The recent uptick in political attacks can be linked to municipal finances as a key source of patronage. The levers of political power at a local level are appealing, as local councillors and political position holders have a significant say in the governance of areas and resource allocation towards service delivery. Because these contexts are characterised by high unemployment rates, the financial benefits and income earned from local government positions often mean the difference between poverty and economic well-being. This consideration also breeds competition over access to such coveted positions, and increases the motivations for competitors to be eliminated.

Through their role, counsellors have a considerable amount of power, directly and indirectly, to have the influence to access municipal coffers through inputs on tenders, contracts for houses, building roads, and the supply of goods and services. This also encourages the involvement of organised criminal elements who want to capture decision-makers in awarding contracts on development projects.

For example, we are seeing the rise of the construction ‘mafias’ in municipalities such as Tshwane, eThekwini and Nelson Mandela Metro; these illegitimate groupings extort fees from new construction and development projects. The failure to comply with instructions, or blowing the whistle on deals, leads to killings. When specific interests are at play, the corrupting influence of power becomes apparent, increasing political tension and the propensity for violence, either between political competitors or with politically aligned entrepreneurs.

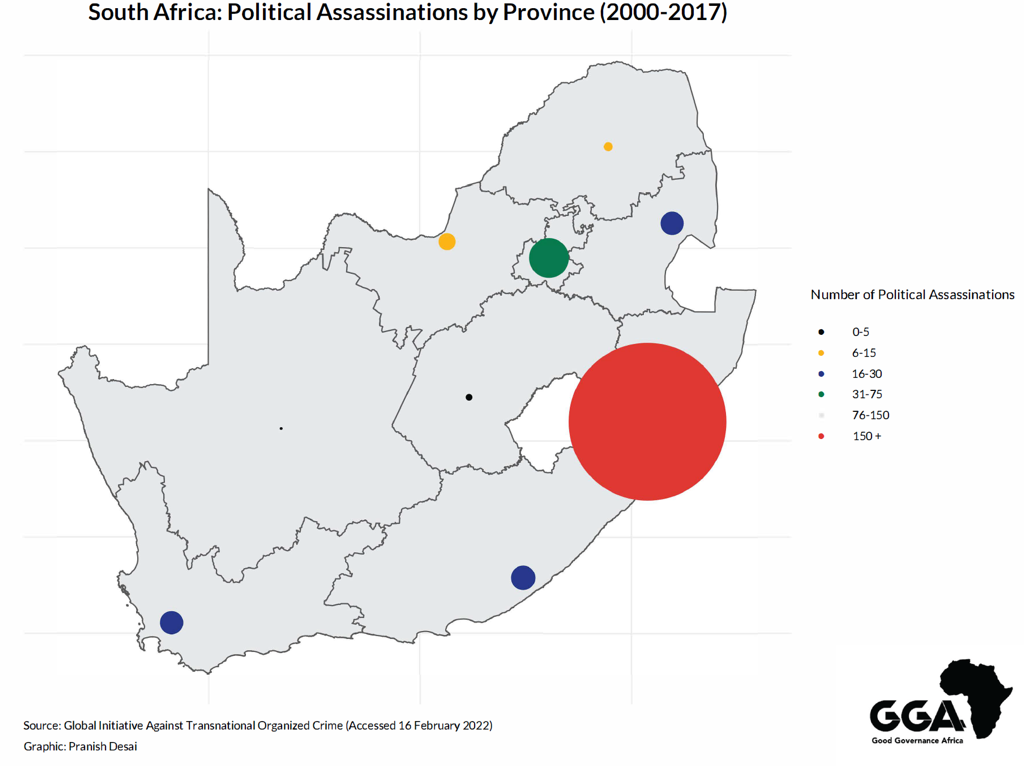

The map above is derived from political assassination numbers reported by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime data. It shows that assassinations are heavily concentrated within the KwaZulu-Natal province. The province remains the hotspot for political violence and occupies a unique position in the country’s violent history. This has been widely documented in the Moerane Commission of Enquiry report. The Commission investigated underlying causes of the murder of politicians in KZN and identified the easy proliferation of illegal weapons, ties to the lawlessness of the taxi violence, and the environment in the infamous Glebelands Hostel as facilitating conditions.

The threats, attempts of violence and assassinations are more common in specific parts of the province and are a growing concern in Pietermaritzburg, the KZN Midlands, and the eThekwini Metro. In the eThekwini metro, where no party enjoys an outright majority following the 2021 local government elections, violence is the result of decision-making in the council hanging in the balance; the killings can trigger by-elections and alter voting patterns towards a particular side, changing decision-making in council.

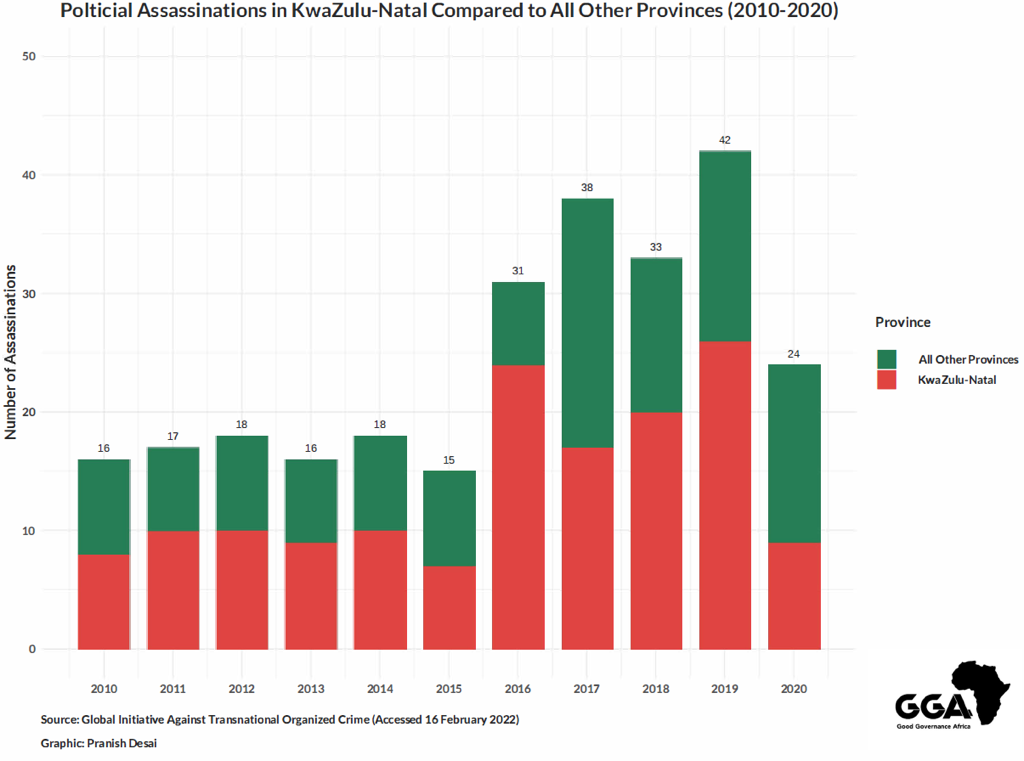

The chart below illustrates the consistent prevalence of political violence within KwaZulu-Natal, especially when compared to the aggregate number of assassinations across all provinces.

The deep-seated battles and internal politics within parties are a part of a growing political culture that generates insecurity in the local landscape. It is no coincidence that political violence becomes more prevalent as the elections draw nearer. This plays out most brazenly at a local level, as party branches are often interlinked with municipal wards. For one, ahead of last year’s local government elections, meetings to elect councillor nominees and ward candidates were marred with violence, with people shot, injured, held hostage, and murdered in multiple regions across the country.

Except for pockets of incidences involving members of other parties such as the DA, IFP, NFP and EFF, the violence predominantly targets ANC members. It can be described almost entirely as an intra-party problem. The ANC will hold its national elective conference in December 2022. Party branches play a crucial role in those elections, which decide the party president, by sending voting delegates. Typically, the branch secretary and chairperson will choose who gets nominated and elected to leadership positions in the party’s provincial and national structures at the conferences.

Given the high stakes involved, and the substantial flow of money and influence, there is a high chance that the frequency of violence and killing will increase in the run-up to the elective conference. The prospect of more conflict is compounded by the evident trend of declining electoral fortunes and fewer majorities for the party. This means fewer opportunities for power and positions, leading to more competition for whatever resources and positions remain. This can also signal a difficulty in conceding and handing power over, from which more violence in attacks and killings will likely follow.

There is little sign that the trend of political killings is reversing. The main problem with this growing political culture is how it brings instability and fragmentation by precipitating leadership changes. The killings create vacuums and political uncertainty by changing how positions are assigned and disturbs electoral leadership processes. It is increasingly likely that political violence could further undermine the democratic nature of the state by eroding trust in the rule of law. The issue is also threatening to erode confidence in institutions of governance, and thus demands urgent attention.

[activecampaign form=1]

Stuart is a Researcher in the Governance Delivery and Impact programme at Good Governance Africa. He holds a Master of Arts degree in Security and Strategic Studies from the University of Pretoria. His dissertation explored the linkages between marginalisation and insecurity, looking at the securitisation of service delivery protests in South Africa. Before joining Good Governance Africa, He was a Junior Research Fellow with the Centre for Law and Society at the University of Cape Town. Before that, he worked as a research consultant at the Institute of Security Studies with the Justice and Violence Prevention Programme and as a Junior Lecturer for the Department of Political Sciences at the University of Pretoria.