Tragic events have recently befallen South Africa – scenes that most of us would like to forget but cannot unsee. Like the riots that broke out in the UK 10 years ago, or the storming of the US Capitol in support of Trump, the orchestrated looting and violence of July 2021 has left many South Africans feeling anxious and powerless.

Analysing the issues

At Good Governance Africa, we set out to read between the lines of what transpired, and continue to do so. We began by interrogating the competing narratives, noting that there was probably some truth to each but that we should be wary of simplistic assertions. The situation truly is complex.

Fault lines in security and intelligence

GGA’s first piece analysed the internal fault lines within the intelligence and security apparatus. We addressed the question of how likely the coup narrative was to be true. The problem is that it simply cannot be verified. There were too many contradictions from various spokespeople within the security structures for us to wholeheartedly digest the idea that the state successfully thwarted a coup, and that the rest of us just couldn’t see it.

The failure of ANC governing strategy

Our second analysis reveals the deep failure of the ANC’s governing strategy. A deep historical dive into the party’s inability to adapt to a changing world, for a host of reasons, suggests a conclusion that the party has to recover its centrist approach and become more pragmatic in the best sense of that word. For the sake of the country it is governing, it needs to become more capable, competent, and strategic.

Protest: lack of services, lack of jobs

Our third analysis showed that the frequency of violent service delivery protests has been growing across the country since 2000. However, frustration with a lack of service delivery, combined with economic marginalisation and disenfranchisement, does not fully explain the riots, given their geographic concentration. It is not as if service delivery has been disproportionately worse in KZN and Gauteng than in other provinces. Governance at the local level is permeated with malfeasance basically everywhere. Nonetheless, grievance clearly provides rationale for violent protest, if not legitimation.

Absence of good governance

None of these analyses are comforting. The bottom line is that the state was caught unawares by a well-coordinated insurrection. From our ongoing analyses, the distilled wisdom is that the chaos can largely be explained by a dire absence of good governance.

Governance is about who gets what, when and how. Essentially, it has to do with the authoritative allocation of resources. The state’s primary responsibility is to govern capably, to allocate resources equitably and efficiently. If it does not, failure ensues, and sinister insurrections gain traction.

In this final piece, we reflect on the state of governance in South Africa, and how institutions can be built and strengthened to render us more robust to destabilising attacks. More importantly, we examine what steps need to now be taken to set us on the road towards inclusive, broad-based development.

South Africa: the quality of governance

The rule of law is an equilibrium state in which no one is above the law. In its ideal and most stable form, everyone is equal under the law and has access to the law. Justice is delivered on the basis of the facts, consistent and rational judicial precedence, and is given credibility by a court system that is competent, professional and independent.

Judicial independence from the executive branch of government is the key to sustaining the stability of the rule of law. This speaks to a related, critical element of a constitutional order – the separation of powers. Regardless of the political landscape, the critical principle that maintains order is that the executive, judicial and legislative spheres of the state remain separate and relatively independent from each other. On this model, the executive is held to account by parliament, with the courts only intervening on rare occasion.

The 1996 constitution is South Africa’s governance manifesto at the highest level. It holds that South Africa is “one, sovereign, democratic state founded on … the supremacy of the constitution and the rule of law …”. South Africa’s electoral system has, however, produced one-party dominance, which was not the original expectation or intention. Proportional representation should lead to a multiplicity of parties competing at the polls, but the ANC’s dominance has left other parties competing for minority votes.

An unfortunate, unintended consequence is that the ANC holds a majority in parliament. Executive desires are rubber-stamped by the majority in the two chambers – the National Assembly and the Council of Provinces. That the courts have had to rule against members of the Executive so frequently is precisely because the intended bulwark of parliamentary accountability has not worked as expected. It has not helped either that the main opposition party’s recent infighting has undermined its electoral credibility.

One-party dominance has had other negative impacts on the country too. Ideally, the state should be crafting and implementing policy and legislation that creates an enabling environment for businesses (especially small and medium sized ones) to flourish. It has not done so. One of the reasons for why RET propaganda has gained traction is that South Africa’s political settlement is characterised by an oligopolistic elite bargain. The dynamics of this equilibrium mean that the majority of South Africans have been excluded from enjoying the minor economic gains that have been made since 1994.

At a basic level, to break the oligopolistic bargains that characterise our political settlement and generate the benefits of free enterprise, the state should provide the following at a minimum: infrastructure that supports broad-based economic growth; education and healthcare that build a highly competent workforce; protection of property (intellectual and physical); and coherent policies that enable businesses to flourish and compete.

The South African state has fallen short on these basic governance requirements. In broad brushstrokes, multiple factors have colluded to crowd out inclusive economic development. It is useful at this stage to locate these factors inside a basic theoretical framework.

Institutions and development

A robust body of research on political economy has shown that institutions matter for development. Institutions that uphold the rule of law and equip citizens to hold the state to account, for instance, typically produce more optimal economic outcomes than their institutionally weak counterparts. Arguably the most useful definition of institutions is that they are the social systems – beliefs, values, norms and cultures – that motivate regular human behaviour. This definition avoids narrowing institutions down to either the ‘rules of the game’ or a basic set of organisations. They are systems that generate incentives. In other words, we should think of institutions as equilibria rather than rules.

If institutions incentivise good governance and provide credible deterrence against looting, unproductive rent-seeking and grand corruption, economic dynamism can take root, which provides the foundation for inclusive development. How to craft these institutions (or strengthen those we have that have been weakened) and make them resilient to distortion is the question that now confronts us as a nation. We cannot begin this work unless we have accurate diagnostics, which requires a brief overview of our history since 1990.

The post-apartheid settlement

Nelson Mandela was released from prison in February 1990. A more powerful signifier that an oppressive era was over is hard to imagine. In the following four years, more lives were lost (largely confined to KZN) than in the entire preceding period of Apartheid combined. The April 1994 elections, however, signalled not only an avoidance of civil war, but a new political dawn.

A new constitution was drawn up by 1996. Constitutions are best understood as commitment devices – they shape the institutions of a nation and can both reverse past trajectories and lay the foundations for a new future. Ours is among the best in the world, a commendable document that enshrines our national aspirations and beliefs, as indicated earlier. But having a great constitution is only the first step; a necessary but insufficient condition for generating inclusive development.

The political settlement was complicated. Members of the new ruling coalition inherited a set of institutions that had been shaped by colonialism and reinforced by apartheid. Under colonialism, infrastructure was designed for the extraction and export of raw material with little opportunity for local value addition. Mining and finance dominated the economy, creating a highly oligopolistic structure with deep path dependence functionally crowding out competition. In the apartheid era, the National Party’s elite bargain was essentially a toxic marriage of government-protected businesses (largely through the Broederbond) and legislation designed to disenfranchise most citizens. Alongside this mix, the colonial dominance of the large mining houses and finance firms continued.

The ‘homelands’ legacy

The migrant labour system, which evolved in the late 1890s when South Africa (or, rather Cecil Rhodes) struck gold, was entrenched through the imposition of a ‘colour bar’ on the mines of the Witwatersrand just after the turn of the century. This prevented skilled black workers from attaining jobs that they were highly competent to perform. Not only were they dispossessed in this way, but they were also forced away from their families left behind in rural areas (and neighbouring countries) for months on end. As a nation, we are nowhere recovering from the effects of this rendering apart of the social fabric.

Migrant labour has, ironically, been perpetuated since 1994, partly because of the path dependence mentioned above – the minerals, energy, and finance complex (MEFC), combined with exclusion from the political settlement, generated and sustained deep inequality. The other part of the reason is connected to the history of land dispossession.

In the early part of the 20th century, under apartheid, expropriation was made worse when the political strategy evolved to create independent ‘homelands’ or ‘Bantustans’. The aim of so-called ‘Grand Apartheid’ was to literally separate South Africans into their tribal homelands. Traditional authorities proved malleable allies in subverting indigenous political organisation to advance apartheid ends. Land under tribal authority was ‘communally’ owned. In other words, allocation to local citizens was at the discretion of the chief. Our constitution recognised the seriousness of the problem, which is why section 25C calls for security of tenure to be restored to those living under insecure communal tenure in the former homelands. Without secure property rights, no economy can truly flourish. Some scholars and political entrepreneurs attempt to deny this, but this basic fact is confirmed by literally thousands of economic studies.

Today, it is estimated that roughly 20 million South Africans live in the former homelands, though estimates vary on this.

A Faustian bargain

Not a single piece of legislation has been enacted to give effect to section 25C. A highly inadequate attempt was made in 2003 through the Communal Land Rights Act (CLARA) but it was opposed by the very communities the act was purportedly meant to benefit and was struck down. The upshot is not only that insecure tenure continues, but the Faustian bargain struck between traditional authorities and the incumbent ruling coalition continues to wreak havoc on our political economy. Insecure tenure continues to drive productive young men to the mines and other urban opportunities, reinforcing past patterns of social disruption.

Moreover, unscrupulous mining companies sometimes take advantage of the loose and highly personalised environment in some former homelands to strike deals with local chiefs at the expense of affected communities and the biodiversity that is often their foundation for ecotourism. They have also, in collaboration with ‘community trusts’ established development accounts (D-accounts) that have essentially acted as slush funds for traditional authorities and local politicians. Most citizens living in these former homelands continue to suffer highly inadequate basic education and constitute a large portion of social welfare recipients.

By 2012, in one disastrous incident, the ill effects of migrant labour combined with the ineptitude of one large mining company to fulfil its social obligations. Marikana proved a vivid picture of South Africa’s fault lines. The discrepancy between rock drill operator and CEO earnings was another glaring picture of inequality, an aortic valve of our national problem.

No clear, consistent economic planning

Migrant labour and land dispossession are of course not the only governance problems, and it is overly simplistic to reduce all explanations for South Africa’s woes to the existence of an MEFC. The government’s prolonged absence of a coherent economic plan (that does not contradict preceding ones), supported by business-enabling policies, is the other side of the coin.

After 1996, the government set out to reduce the country’s external debt and to implement an economic action plan known as Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR). GEAR was underpinned by fiscal austerity (reducing the wage bill in a bloated public sector), floating exchange rates, and labour unhinged from unions demanding higher real wages alongside declining productivity. The big idea was to signal fiscal discipline to the global market as a foundation for attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI was meant to grow employment (and consequently the tax base) and fund redistribution to redress past injustice.

The plan had its deficiencies, especially given its assumptions about a free labour market, but the South African economy did relatively well nonetheless until the global financial crisis (GFC) hit in 2008. Our subsequent failures, however, have had less to do with the aftermath of the GFC and more to do with dynamics within the ruling coalition and its resultant misgovernance.

The tragedy of misgovernance

In 2007, Thabo Mbeki was ousted by the very man he thought he’d seen the back of – Jacob Zuma. Zuma brought with him to the ANC structures the Zulu vote that had essentially been the domain of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) until then. The importance of this for shaping internal ANC dynamics since then has probably been underplayed in the national discourse – not least because the ANC’s long fight against apartheid was built on preventing ethnic division. The ANC tends to be very sensitive, it not denialist, when signs of ethnic activism do emerge within its own ranks.

Yet the post-GFC dynamics within the ruling party, with Jacob Zuma at the helm -whose policies and appointments were often shaped by a barely disguised ethnic chauvinism – almost brought the country to its knees. State capture, grand corruption and the enablement of looting at every level of government has caused severe socio-economic distress. The headline data paints an abominable picture:

Youth unemployment

Youth unemployment (age 15-24) ballooned from 51.7% (already high) in 1996 to 60.8% in 2003. In 2008, it declined to a low of 44.8% and has subsequently risen to 63% in the first quarter of 2021. Frustration over this lack of access to economic opportunity is a deep vein of resentment into which the likes of the RET brigade and one of its fanatics, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), can easily tap.

An unemployed graduate in a demonstration at Church Square in Pretoria on 14 August 2020. Photo: Phill Magakoe/AFP

Fiscal stress

Since 2016 our national debt to GDP ratio (what we owe to creditors as a proportion of our overall wealth) has shot up from 51.47% to 77.06% in 2020. Statista (a data company) projects that the figure will be 94.9% by 2026. With a dwindling tax base and stagnating economy, it goes without saying that this is unsustainable. We will end up spending more of our budget on servicing debts than on investing in health and education, and human and physical capital formation (infrastructure). Tax revenue as a share of GDP hovers consistently at around 20% (22.6% in 2020), which is too small to sustain our population of roughly 60 million people.

Inequality

Globally, and in South Africa, inequality (especially since Pickety’s big book on the matter was released) is singled out as being fundamentally responsible for unrest, violent protest and all that is wrong with our society. The evidence is clear that unequal societies do poorly on just about every development indicator.

In 1996, the income share held by the highest 20% of income earners in South Africa was 65.9%. By 2000, that figure had decreased to 62.6%. By 2005, it had risen to 71% only to drop again to 68.7% by 2008. The last World Bank figures available from 2014 show that the income share held by the highest 20% was 68.2%. The income share held by the lowest 20% of income earners was a trivial 2.4%.

More broadly, 80% of the country own 31.8% of the wealth between them. The tail is extremely fat. As of 2020, according to Astons, the richest 1% of South Africans earn 9.3 times as much as the average citizen. We were said to be the world’s most unequal country with a Gini coefficient of 0.63 (where 1 is the most unequal and 0 the most equal) in 2014. However, a caveat must be added here: the Gini coefficients of several upper-middle-income countries are not reported.

A narrow tax base

In the South African context, this wealth gap is especially challenging. The wealthy (our narrowing tax base) fund our growing social welfare requirements (currently 18 million people). In 2019, only 6.6 million people were expected to submit tax returns (a thin 31% of the 22.1 million registered taxpayers). In other words, only 10% of the country’s population is paying tax. And an even smaller percentage (5.8% of the total population) provide 92% of all personal income tax (the other 4.2% only earn enough to contribute 8% of the total amount). To further diminish our prospects, the total public sector wage bill is at 12% of GDP, too large to sustain; it is 42% higher than the total personal income tax received by the revenue service in 2020.

But these taxpayers, who own the top 20% wealth-share, also earn a significant sum more than the average citizen. This one fact is an important source of relative deprivation, which underlies much post-apartheid pain. It also fuels a narrative that the political freedom wrought in 1994 will be meaningless until economic inequality is overcome.

Addressing inequality

Inequality is not so easily addressed, however. Redistribution is a blunt instrument. It is painfully obvious that the factors which drive inequality must be reversed. But this is easier said than done. Redistribution without growth is unsustainable, so growth is clearly part of the answer. However, growth without structural transformation is likely to be meaningless, as gains will accrue to the already-wealthy at the expense of the uneducated and unemployable.

What is largely missing from the public debate at this stage is a deep focus on the relationship between governance and long-run inclusive development. The global evidence is clear that democracy causes economic growth. In other words, political and governance changes associated with democratic orders drive economic success. One reason is a positive feedback loop: economic success grows the middle class, which is then able to insist on better governance performance from its political authorities.

South Africa’s middle class is paper thin, though, and highly indebted. And even if it was politically unified against the corruption evident in the ruling coalition, many members of this sector of society sense that they exist in a relatively choiceless democracy.

Misgovernance: tallying the cost

There are many lenses through which the post-GFC episode of South Africa’s economic collapse can be understood. But one which perhaps most starkly illustrates the relationship between governance and growth is electricity.

In a nutshell, South Africa had an opportunity in 2008 to start transitioning away from fossil-fuel based electricity (dirty coal). Had the state created an enabling environment for investments into renewable energy and sustainable transport, our economic record might have looked far different. Instead, the state actively suppressed its very own remarkable success vehicle in the form of the REIPPP – the renewable energy independent power producer programme. The declining costs of renewables over time are well-documented. It would have been eminently sensible to expand the programme while decommissioning expensive coal-fired power plants.

Instead, in 2012 (after having failed to invest as suggested above), the state set about building Medupi and Kusile, two of the world’s biggest coal-(and-money)-burning megaprojects. A decade later, cost overruns and ineptitude mean that they are still not generating at full capacity. They also produce electricity that is more than double the cost of solar power per kilowatt hour. To add tragedy to farce, an explosion at unit 4 of Medupi this week has caused “extensive damage” to the generator.

In 2013, Zuma attempted a nuclear deal with Putin’s Rosatom, which thankfully was never signed off. The argument was that we needed baseload power. It is more likely that Zuma needed Putin’s cash to pay his personal tax bill. Putin is probably still after Zuma for the lost deal. Perhaps this partially explains former president Zuma’s reported ill health.

As if that was not enough, Eskom – the state-owned enterprise now in debt to the tune of about R500 billion (roughly 50% of the value of the entire country’s national budget) – became the primary looting vehicle for the ‘Zupta’ regime. In one instance, Eskom advanced a prepayment of R1.68bn to a Gupta-owned company, for doing nothing productive.

Under Zuma, the ANC’s failures in relation to one of the most basic factors in any modern economy, electricity, have cost the country enormously. The consequent damages to the economy from Covid-19, looting and violent unrest have not been fully tallied. The lag effects will erode our potential for inclusive growth for many years to come.

Zuma’s long Stalingrad strategy of abusing the law to stay out of jail finally came to an end in July this year, when he was jailed for defying the Zondo Commision of Inquiry into state capture. At the time, we said that Zuma’s incarceration was good news for South Africa. We said this because the sentence, handed down by the Constitutional Court, signified that the rule of law has been upheld at the highest level.

Growth and the Narrow Corridor

One of the reasons why countries characterised by constitutional orders grow is because investors know that their property is secure, and their investments will be honoured. The fact that the stock market hardly reacted to the looting and violence in South Africa shows that investors still believe – despite the shocking lack of governance on display – that South Africa is a solid prospect for long-run returns. Additionally, at least to some extent, they have factored the costs of current fragility into their decisions.

What generates sustainable economic dynamism? One promising theory here is articulated in the idea of a Narrow Corridor. Essentially, countries that get onto the pathway of inclusive development have a dynamic and mutually reinforcing relationship between state capability and citizen strength. If the state is overly powerful and citizens are suppressed, then long-run growth is jeopardised. China is an example of this. If the citizens are powerful but exist in a relatively stateless society, or a context characterised by state ineptitude, that country will find it challenging to generate inclusive long-run development. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one such (albeit imperfect) example.

GGA’s Governance Coefficient

Inspired by this theory, GGA has built a ‘Governance Coefficient’ to prise open the black box of governance. To provide some quantitative rigour to the narrow corridor concept, our Governance Coefficient locates countries in relation to ‘government effectiveness’ and ‘citizen voice and accountability’.

Subscribers to our website will see that the Governance Coefficient displays countries by colour in terms of GDP per capita size. Technically, improvement in the two governance variable scores should correlate with an increased GDP per capita. Some exceptions prove the rule, especially in oil-wealthy developing countries, where GDP per capita is high but the rents accrue only to members of the ruling elite.

The static 2019 version of our Governance Coefficient indicates that most European countries, along with North America, are firmly within the narrow corridor. Singapore and China have effective governments, but citizens are relatively powerless. The theoretical prediction is therefore that they will be in for a hard landing at some point.

In 1996, South Africa scored relatively well on both counts. Since then, it has been a mixed bag. By 2019, our position had worsened considerably and GDP per capita remains low at $6001. We scored 0.67 (on a scale running from -2.5 to 2.5) on citizen voice and accountability (down from 0.84 in 1996), and 0.37 on government effectiveness (down from 1.02 in 1996).

The rule of law and development

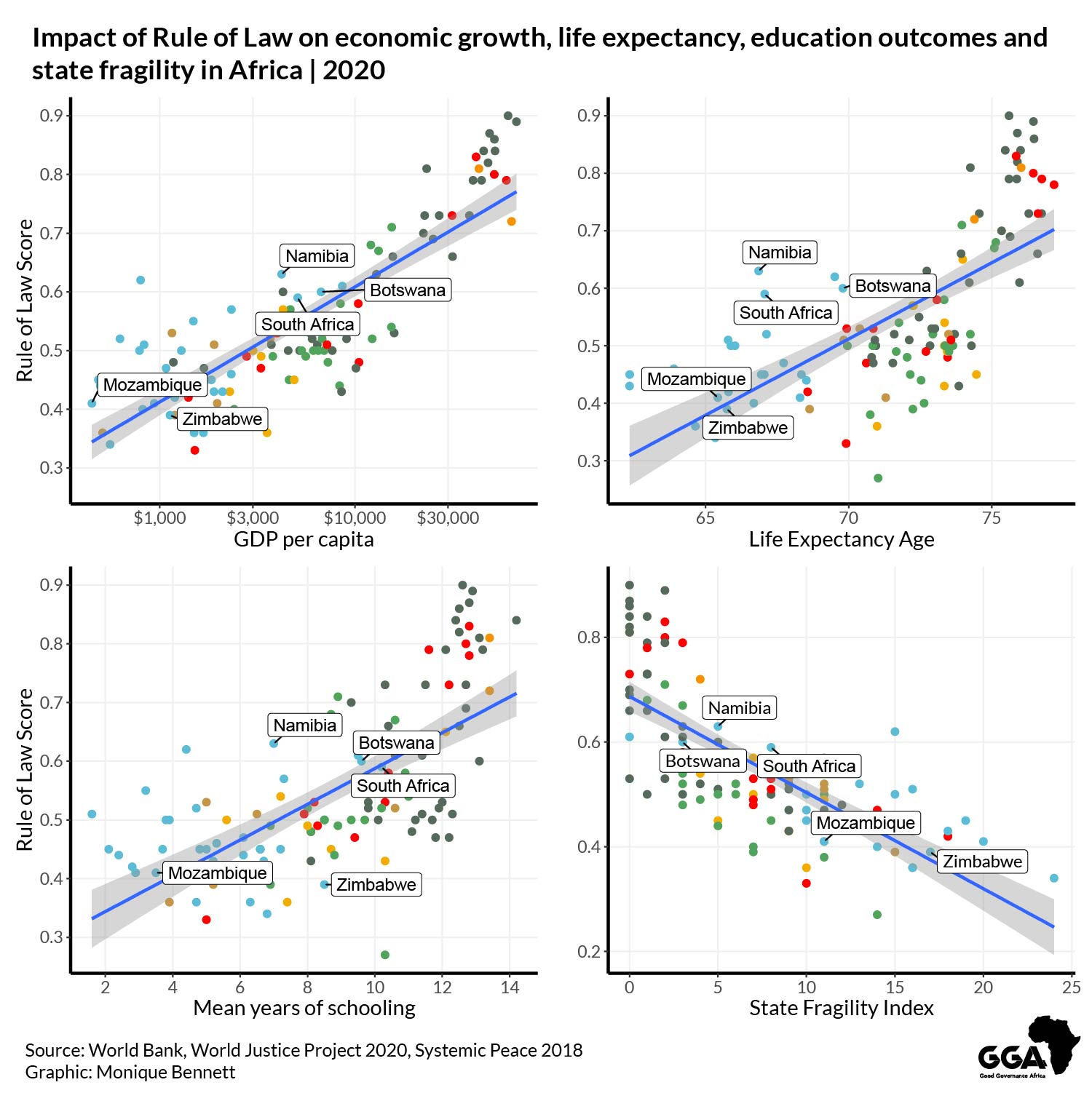

GGA also collates and conducts research into other factors that influence the quality of governance. The graphs below are derived from our research in these areas, and they illustrate other relationships between the rule of law and indicators of development prowess. The graphs show that life expectancy, GDP per capita, and mean years of schooling achieved are all positively related to governance under the rule of law. States that fail to achieve or uphold the rule of law, however, experience greater fragility.

Correlation is not causation, but the econometric evidence strongly suggests a causal relationship between governance and growth, with the former driving the latter and not the other way round. Focusing on building strong and coherent political institutions, in other words, will reap economic rewards and generate a mutually self-reinforcing virtuous cycle.

Lessons for South Africa

The lessons of these reflections for South Africa are not simple but it is worth offering some in closing.

Amid the violence that unfolded last week, the Zulu king (now somewhat famously) remarked that the Zulu nation was committing suicide. Zuma said nothing condemning the violence and was apparently quite happy for his henchmen to threaten this kind of unrest if their man was ‘touched’. If it is indeed the case that intelligence about the planned post-jail insurrection did not reach the people whose job it was to pre-empt and prevent it, then questions must be asked about where loyalties lie across the intelligence and security apparatus. If it did reach them and they didn’t respond, even more questions must be asked.

A cabinet reshuffle will not immediately solve the problem, either. President Ramaphosa has to allocate his political capital carefully. He has had to spend a fair amount of it to ensure that Ace Magashule was suspended from the ANC earlier this year, for example. This was no small feat given the tiny majority with which Ramaphosa won the ANC general elective conference of 2017.

We should also remember that Ramaphosa has made significant progress in restoring the very institutions of the state that should have ousted Jacob Zuma when obvious signs of corruption first appeared (such as the judge’s ruling of a generally corrupt relationship between Zuma and Shabir Shaik). Ramaphosa has appointed a new head of the National Prosecuting Authority, the Hawks and a new head of police intelligence, replacing their incompetent and dubitable predecessors. A few thorns in his side remain, though, especially the Zuma-appointed public protector and a defence minister who openly contradicts him. The courts have found the public protector’s recent cases against Ramaphosa laughable, but she remains in her post.

Here are some crucial lessons to be drawn from the mayhem of July:

Executive decisiveness

First, President Cyril Ramaphosa needs to exercise more boldness in firing incompetent ministers from his cabinet, especially those who contradict him in public and have failed to perform in crisis moments. As difficult as this may be considering the delicate political calculus at play within the ANC, the country requires bold leadership. The ANC itself – as argued previously by GGA – requires a strategic shake-up and to start adopting new ideas that will see South Africa into a more promising future.

Defending the rule of law

Second, South Africans need to band together to defend the rule of law against the insurrectionist bandits who would see it toppled. The evidence is clear that the rule of law is key to effective development, and this applies especially with regard to the behaviour of members of ruling elites. For example, the rule of law defends societies against the kind of personalised deal-making that became normalised under the ‘Zupta’ regime. Countries without the rule of law are unlikely to transition into the narrow corridor where economic dynamism becomes entrenched through a virtuous politico-economic cycle.

Security capability and consistency

Third, the leadership of the ruling coalition must eradicate the contradictions within the security and intelligence apparatus that have evolved through both looting and factionalism.

Government effectiveness, citizen voice

Fourth, government effectiveness and citizen voice and accountability must both be radically improved to set South Africa onto a new growth trajectory. These two must grow together to achieve what Acemoglu and Robinson have called the ‘red queen’ effect, in which the state grows in sophistication and effectiveness, while citizens grow in their ability and power to hold such a state to account. The ‘red queen’ (from Alice in Wonderland) is essentially running to stand still. It is in the sweet spot of capability and accountability that economic dynamism can flourish.

Pledging to Good Governance

In concluding, South Africa’s active citizenry has banded together against the bandits who would see us reduced to ruin. Amidst executive-branch incompetence at running an effective state, the judiciary has stood firm against members of the political elite whose rule was at least partially responsible for fomenting government incapacity. These are two positive factors to draw from these recent events, and both point to the need for citizens to pledge to seeing Good Governance become a reality for our nation.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.