During a previous African Governance Architecture meeting, the African Peer Review Mechanism chief executive Professor Eddy Maloka called for the continent to be robust and frank when dealing with governance matters. He shared his concern about the deteriorating trend in governance in Africa and called on the African Union (AU) to find ways to address this serious matter.

According to studies, Africa is grappling with democratic backsliding. In 1985 there were only three democracies while there were 42 authoritarian regimes on the continent. By 2015, the number of democracies had reached 22. However, democratic backsliding saw the number shrink to 18 democracies compared with 19 authoritarian regimes and 13 hybrid ones in 2020.

This trend appears to have gained a footing in some countries as certain presidents have sought to manipulate their prescribed term limits and alter their constitutions to extend their term in office. This is unfortunate as it threatens to undermine the expansion and promotion of democracy and good governance across the continent. The expansion of democratic norms has been a positive trend that has taken root in many African countries.

While most African countries have presidential term limits crafted into their constitutions, this has not deterred some presidents from seeking to manipulate the legal process.

According to data from the Open Society for Southern Africa (OSISA), between April 2000 to July 2018, term limits were changed 47 times in 28 countries, with at least six failed attempted changes. In 23 cases, spread over 19 countries, the changes strengthened term limits by introducing or imposing stricter temporal boundaries on presidential mandates, but in 24 instances in 18 countries, the temporal restrictions on holding presidential office were removed or loosened.

Term limits remain crucial for the promotion of democracy and good governance as they are important safeguard measures to prevent tyranny and guarantee the peaceful political transition from one elected president to the next. This safeguarding measure and peaceful political transition are the cornerstones of any healthy democratic state.

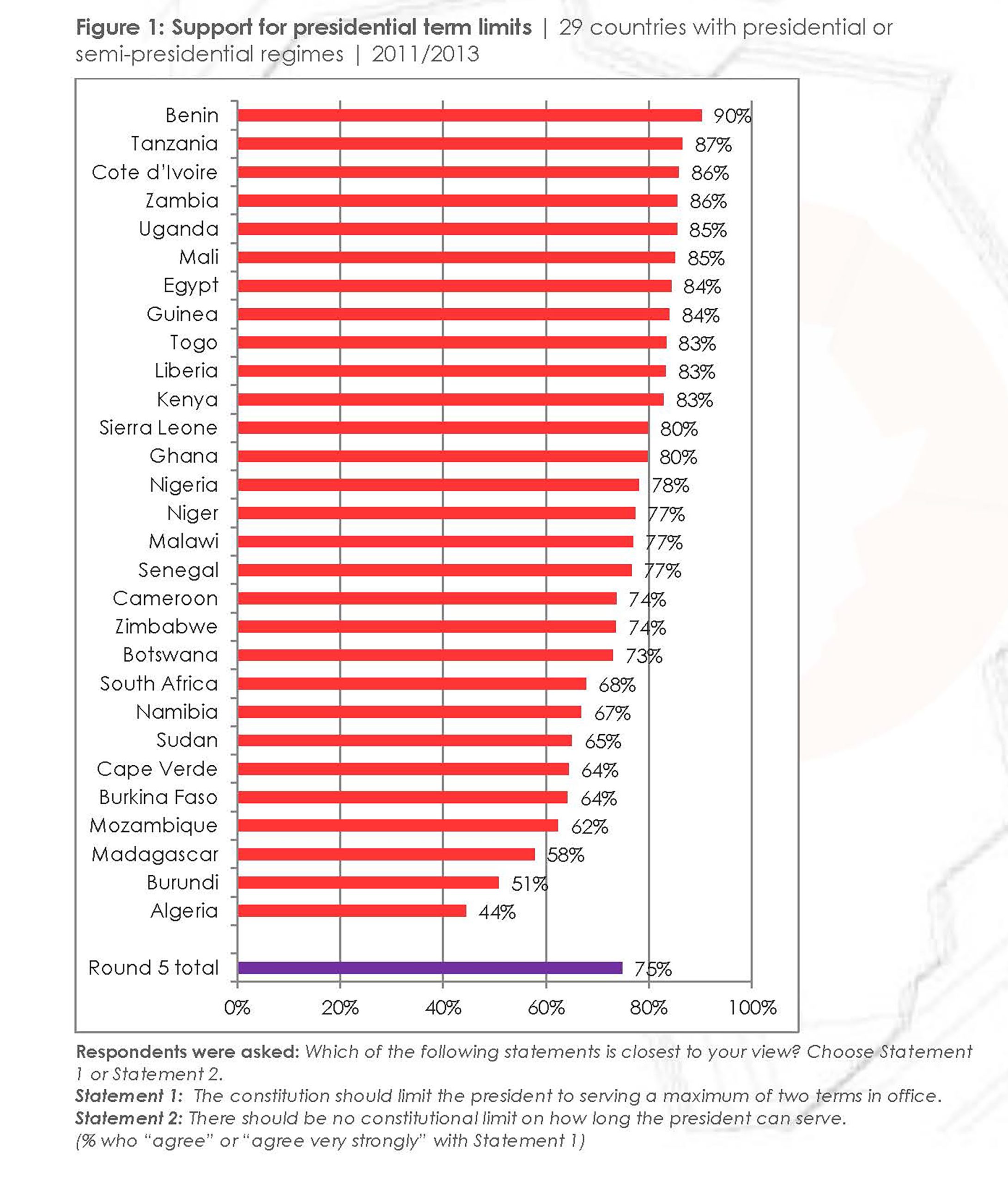

Results from an Afrobarometer survey found that citizens are in favour of presidential term limits. Across 34 countries, an average of 76% favour limiting their presidents to two terms, including a majority (54%) who “strongly” support this rule.

Nevertheless, changes in term limits on the continent have been executed in four different ways which include:

Firstly, the amendments extended the length of presidential terms of office: from five to seven years as is the case in Guinea (2001), the Democratic Republic of Congo (2002), Rwanda (2003) and Burundi (2018); and from five to six years in Chad (2018). Presidential terms were also extended in instances of intra-state conflict and capacity problems when elections were postponed in South Sudan (2015 and 2018) and the DRC (2016).

Secondly, changes increased the number of terms a person may hold presidential office, from two to three terms in the DRC2015).

Thirdly, changes were made to reset the presidential term clock for the incumbent president, as seen in Zimbabwe (2013), the DRC (2015) and Rwanda (2015), where the incumbents had reached their absolute term limits but could argue that a new or revised constitution allowed them to start with fresh mandates unrestricted by previous constitutional limits.

Fourthly, term limits were removed altogether in Guinea (2001), Togo (2002), Tunisia (2002), Gabon (2003), Chad (2005), Uganda (2005), Algeria (2008), Cameroon (2008), Niger (2009) and Djibouti (2010).

Criticism has been levelled at the AU that the organisation does not do enough when presidents tamper with term limits. However, the AU in a pre-emptive measure to deter authoritarian leaders from attempting to alter their term limits, formulated the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance. The Charter, after much campaigning and support from civil society, came into existence in 2012 after the required number of countries ratified it.

The document is important as it has comprehensive provisions for the promotion of the rule of law, the respect for human rights and the holding of democratic elections “to institutionalise legitimate authority of representative government as well as democratic changes of government”. Additionally, it binds signatories to best practices in the management of elections; and crucially acknowledges that unconstitutional changes of government are “a threat to stability, peace, security and development”.

The AU should be commended for committing AU member states to refrain from the “amendment or revision of the constitution or legal instruments, which is an infringement on the principles of democratic change of government” as one of the “illegal means of accessing or maintaining power” by having these phrases included in the Charter.

Nonetheless, some critics have argued that this approach was a compromise following the rejection of a proposal to specifically impose a two-term limit across the continent. If the Charter is to be a true benchmark for African governance, adopted by member states, the AU and the African leaders should be firm and decisive in their response to malevolent leaders who attempt to, and succeed, in altering their constitutions to remain in power after their term has been completed.

The adoption of the Charter has been described as “a new dawn for democracy and the rule of law in Africa”, but if it is to fulfil this mission more should be done in formulating adequate response measures towards leaders seeking to alter their term limits. For this to be the true benchmark for African governance, the AU as the continental governance custodian and its member states should be more proactive, when necessary, in calling leaders who change their constitutions to stay in power to account.

This article has attempted to respond to Maloka’s call by encouraging frank and robust discussions on some of the governance concerns affecting the continent. Evidently, there is a need for deeper analysis and the formulation and implementation of relevant collective policy responses aimed at promoting democracy, good governance, and respect for human rights.

The following are some considerations for African policymakers:

- With several African countries set to head to the polls in 2023, protecting civil rights and democratic processes should be treated as a critical issue by member states and regional organisations in upholding Africa’s democratic gains.

- AU member states should be cautioned against manipulating public crises as a political means to extend their stay in office.

- Sanctions on leaders who unconstitutionally extend their stay in office should be decisive to avoid mixed messages that may inadvertently encourage others to do the same. The AU should be firm on response measures to presidential term abusers with the support of the RECs and member states.

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.