Ersuolo Ermako serves a young customer at his tuck shop in Majakaneg township, near Marikana, 2014. © Graeme Williams

Ethiopian immigrants seek opportunities in South Africa, and a leg up the socio- economic ladder

With an estimated population of nearly 95 million in 2017, Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, second only to Nigeria. More than 80% of the country’s population live in rural areas.

Largely as a result of the political and economic reforms introduced since the early 1990s, the country’s economy has grown dramatically for more than a decade. A massive expansion of infrastructure and social services – such as primary health care and education – has been instituted. Yet most Ethiopians still depend on subsistence agriculture, which is vulnerable to drought.

Amid economic growth and signs of structural change in the economy, the country has been gripped by waves of violent protests over the past two years. After months of protests, the federal government declared a state of emergency throughout the country in October 2016 and the country is still under emergency rule. The causes for the unrest are complex, and include economic and political factors, but youth dissatisfaction and unemployment are among the factors that have fuelled the protests.

With a higher level of population growth and the obvious inability of the Ethiopian economy to absorb the more than one million new entries to the job market every year, international migration has emerged as one important strategy young people use to escape poverty. That is why there has been a significant rise in outward migration from Ethiopia in recent years. The major destinations of Ethiopian migrants are the oil rich Gulf countries, North America, Europe and South Africa.

Remittances from migrants support hundreds of thousands of households in Ethiopia every year. Moreover, in recent years, remittances have become the most important means of securing foreign exchange for the country. The country earned close to $4 billion from remittances, while remittances outperformed exports in 2016, according to the Ethiopian ministry of foreign affairs.

Ethiopian migration to South Africa is a relatively recent phenomenon. It started in the early 1990s and had gained momentum by the 2000s. Migrants to South Africa predominantly come from southern Ethiopia, and the majority of them are young men. No verifiable data on the number of Ethiopian migrants in South Africa is available, as the majority of them are undocumented. Some recent estimates, however, put the number of Ethiopians living in South Africa at about 120,000.

A key driver behind Ethiopian migration to South Africa is poverty. Many of the areas in southern Ethiopia that are most affected by migration to South Africa face population pressures and a shortage of farmland. Another driver of migration to South Africa is peer and family pressure. The success stories of some migrants who have succeeded in changing their economic status after migrating to South Africa have fuelled the desire to migrate. Illegal brokers and traffickers also incite young people to migrate by spreading false or highly exaggerated stories about their glowing prospects in South Africa.

Ersuolo Ermako enjoys a meal with compatriot Ethiopians who have made a home in South Africa’s North West province. © Graeme Williams

Migrants spend substantial sums of money to travel to South Africa. Recent estimates put the price tag of migrating to South Africa at between $4,000 and $5,000. More often than not, parents and close family members cover the cost of migration. Families even resort to selling valued property and taking loans at exorbitant interest rates from illegal lenders.

Almost all migrants to South Africa start their journey by securing a passport from the relevant government department. Once they have their passports, they decide what routes and mode of transportation to take. Generally, Ethiopian migrants get to South Africa by air or overland. Prospective migrants use a range of pretexts to get into the country – business, medical treatment, education or family visits. In recent years, the air travel option appears to be less favoured, due to tighter visa and border entry controls.

The second, and more dangerous, route to South Africa is overland, which involves travelling by vehicle, in some cases boat, and walking long distances on foot. Overland travellers are exposed to different kinds of hardships. The inland journey takes place under the control of strong networks of traffickers living in the countries the migrants pass through, and the migrants are usually smuggled into South Africa.

Ethiopians often en- counter distressing stories in the Ethiopian national media about what can happen during the journey: severe maltreatment by brokers and traffickers, loss of life due to accidents and xenophobic attacks. Yet, migration to South Africa shows no sign of slowing down. Ethiopian migrants to South Africa are often economic migrants, but they usually apply for asylum after their arrival; South African law allows asylum seekers to work and study pending the processing of their applications.

Having arrived, Ethiopian migrants start working straight away. Most commonly, and particularly during their early years, they get involved in street vending in cities, townships and villages. They sell a range of goods, including bed sheets, bed covers and household appliances, offering deals in cash or credit. In townships and rural areas they are known as hoza-hoza traders. The profit margins are said to be attractive, but the street vendors face high levels of risk. They might be denied payment for goods sold on credit, or be robbed or attacked by vigilantes.

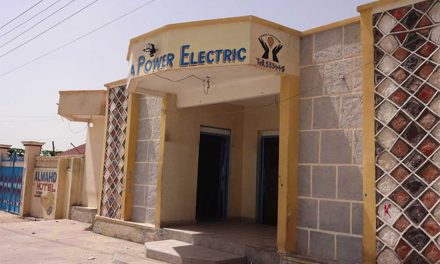

With their increasing knowledge of their environment and as they accumulate sufficient capital, migrants gradually change their jobs from hoza-hoza trading to better-income businesses, including setting up small stores, providing transport services and opening restaurants. Some successful migrants start small-scale import businesses that import merchandise from China for distribution to hoza-hoza and other retailers.

In South Africa, the high rate of unemployment – particularly among the historically marginalised black population – and high levels of migration from other African countries have created resentment against migrants. In recent times, ill feeling among sections of the black population towards migrants has become quite open. Like other African migrants, Ethiopians were victims of the waves of xenophobic attacks in 2008 and 2015.

Migration to South Africa has had both a positive and negative impact on Ethiopians. Household economies have benefited from remittance money, which is used not only to meet daily expenses but also to build household assets. Indeed, some households use remittance money to start businesses, buy business vehicles and build rental homes.

Migration to South Africa has also had a negative impact on Ethiopian society. Aside from the hardships the migrants face en route to South Africa and after they arrive there, the phenomenon is also having an adverse effect on levels of education. Community members and teachers report an increase in the number of young people, especially young men, who drop out of school. They attribute this to aspirations inspired by stories about successful migrations to South Africa.

In recent years the Ethiopian government has begun to take measures to curb irregular migration, especially to South Africa. In particular, it uses the media to educate the public about the risks. The government has also adopted a tougher stance on brokers and traffickers. In 2015, the federal government adopted a proclamation aimed at preventing and stamping out trafficking and migrant smuggling. In the same year, the federal high court found 106 people guilty of human trafficking and sentenced them to between two and 11 years’ imprisonment.

In South Africa too, there has been an effort to revamp the country’s immigration policies. In March 2017, the cabinet approved a white paper on international migration. The new policy could remove the automatic right asylum applicants have to work or study in South Africa. It could also provide for the establishment of border-processing centres for asylum seekers.

Ethiopian migrants in South Africa and their families have mixed feelings about illegal migration to South Africa. On the one hand, they consider migration as a means to escape poverty, an ideal opportunity to get initial capital to launch a new life and support their families. On the other, they say that they live in constant fear and anxiety due to the hardship of the journey and the xenophobia migrants experience in South Africa.

Equally, academic researchers and international organisations, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), express their concern about the dangerous journey to South Africa and the legal and socio-economic status of migrants after they arrive in the country.

While efforts to tighten the loopholes in migration policies are important, it is equally important for South Africa to work with the origin and transit countries to clamp down on the network of traffickers and smugglers. At the same time, it will be important to consider ways of regularising the tens of thousands of Ethiopian migrants who currently live and work in South Africa.