To many in the research community, Africa remains an anomaly, as it has experienced less of the coronavirus burden than many other regions in the world. According to the Africa Centre for Disease Control (AU CDC), as of 27 January 2021, at least 40 countries are experiencing a second wave of the pandemic, including all countries in the SADC region. As of 2 February 2021, the confirmed number of Covid-19 cases from 55 African countries reached 3,582,328.

On the continent, South Africa is the outlier, with the highest percentage of recorded active cases of the coronavirus. Based on the available data, South Africa is the epicentre of the pandemic on the continent, and as such the South African Development Community (SADC) finds itself, by extension, in the same situation. SADC member states have experienced a spike in infection numbers attributed to the ‘second wave’ and secondly, to the more recently discovered new variant of the virus known as 501Y.V2. Up until now, more than 50% of all new daily infections of COVID-19 on the continent have been reported in the SADC region.

Factory workers check personal protective equipment for COVID-19 frontline health workers at a factory commissioned by the government in Accra, Ghana, April 2020 Photo: Nipah Dennis/AFP

South Africa’s discovery of the new variant has corresponded with a new surge in infection numbers. Researchers have claimed the new variant is around 50% more contagious, based on the much faster rate of COVID-19 transmission, as it appears the new variant structure enables easier attachment to and infection of human cells.

The alarming increase in new infections in the SADC in the first two weeks of January 2021 saw the total number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases surge to 346 010, accounting for about 22% of the total number of cases registered since the beginning of the pandemic in the region. Concerns are mounting that the higher percentage of regional infections are being driven in part by the new variant which, according to the AU CDC, has so far been reported in three SADC countries. With the faster rate of transmission, it is only a matter of time before other SADC countries record infections related to the new virus variant.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has hampered both social and economic activities in SADC countries to varying degrees, it has also had a detrimental impact on the governance capacity in the region. Since the end of 2020 and the start of 2021, SADC member states have lost ten cabinet Ministers from four countries who succumbed to the coronavirus:

Zimbabwe – Transport Minister Joel Matiza, Foreign Affairs Minister Sibusiso Moyo, State for Manicaland Provincial Affairs, Ellen Gwaradzimba and Minister of Lands, Agriculture and Rural Resettlement Perrance Shiri

Malawi – Transport Minister Sidik Mia and Local Government Minister Lingson Berekanyama

Eswatini – Prime Minister Ambrose Dlamini, Minister of Labour and Social Security Makhosi Vilakati and Minister of Public Service Christian Ntshangase

South Africa – Minister in the Presidency Jackson Mthembu

Unfortunately, unless there is a drastic change in the rate of transmission, it is anticipated the above list will grow as the variant takes hold in all SADC member states. As states remain the chief bearers of the responsibility to govern, there is an inherent expectation of them to provide and implement political, social and economic measures to service the expectations of their citizens. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened this responsibility of the state apparatus, as the normal livelihoods of the citizens may have been disturbed. Thus, citizens have found themselves in a position where they must rely more on the state to formulate policies and provide means to mitigate the devastating effects of the pandemic on their livelihoods. Without a doubt, there is an expectation of the states to formulate and implement adequate policy interventions to address the negative impact of the pandemic, while still providing effective service delivery and maintaining good state-society relations. With a view to attaining these goals, more so in times of crisis, states should continue upholding the rule of law, respecting fundamental human rights and freedoms, be accountable and ensure inclusive and participatory democratic governance.

With the death of several SADC political leaders from Ministries that were tasked with dealing directly with providing goods and services to the society at large, it adds only to the already heavy burden of the state to provide for even the most basic needs of their citizens.

However, as the adage goes: ‘in crisis lies opportunity’. This may be the opportunity for SADC member states whose primary responsibility remains to govern, to reflect on lessons that have emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic. These lessons may require SADC leaders to be open to having deeper, difficult deliberations around the possibility of re-energising the role of the state in good governance practices in the region in particular, and the continent in general. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the limitations states have in adequately addressing emerging challenges such as a pandemic. States have to be more resourceful in developing sophisticated means to address the scourge of inadequate service delivery, which was heightened and on display during the course of the pandemic. If this threat is left to fester, it may increase instability which in turn impacts negatively on governance, peace and security on the continent.

An alarming underlying feature which emerged during the pandemic was the high occurrence and degree of lack of accountability and corruption in both the public and private sectors in the procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE) to curb and manage the threat posed by the pandemic, while undermining effective good governance practices. In the case of South Africa, it is unlawful for public servants to do business with the state, but there have been several high profile public servants accused of abusing their positions or proximity to power to exploit the emergency procurement regulations. This enabled some government officials and their families to rake in the millions through alleged corrupt deals with opportunistic companies that emerged suddenly and diversified into the PPE market. According to Tedros Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organization: “Any type of corruption is unacceptable. However, corruption related to PPE… for me it’s actually murder. Because if health workers work without PPE, we’re risking their lives. And that also risks the lives of the people they serve. So it’s criminal and it’s murder and it has to stop.”

Moving forward, there should be a change in approach in which the SADC as a region seeks to remedy the prevailing trust deficit. Regional leaders should endeavour to uphold the social contract through inclusive and participatory governance with the aim of positively delivering to the citizens. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how the most vulnerable of the population, including women, children, youth and persons with disabilities carried more of the pandemic’s burden. The SADC member states should therefore seize this opportunity in this time of crisis to strengthen their capacity for achieving adequate service delivery, continued respect for human rights, upholding the rule of law, constitutionalism and transparency.

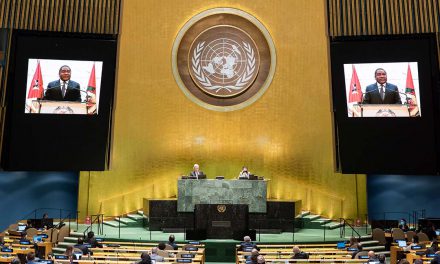

In a recent statement, President Filipe Jacinto Nyusi of Mozambique, in his position as the current SADC Chairperson, strongly encouraged the region to “build on the knowledge and experience achieved in mitigating this pandemic and continue to adopt common and harmonised policies, guidelines, strategies and measures in response to the pandemic.” Let us hope that he is true to his call and the SADC will not miss this opportunity to strengthen its good governance principles. It is imperative going forward that best practices and lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic are formulated into policies and implemented to benefit the citizens of the region.

This article also appeared in the Cape ARGUS.

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.