Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana’s maiden budget speech appeared to make all the right noises. It referenced the state of the nation address, gave some substance to the ambitions outlined there, and was mildly honest about some of the risks affecting our fiscal future. But it lacked a critical focus on key governance outcomes and a real strategy to address the risks.

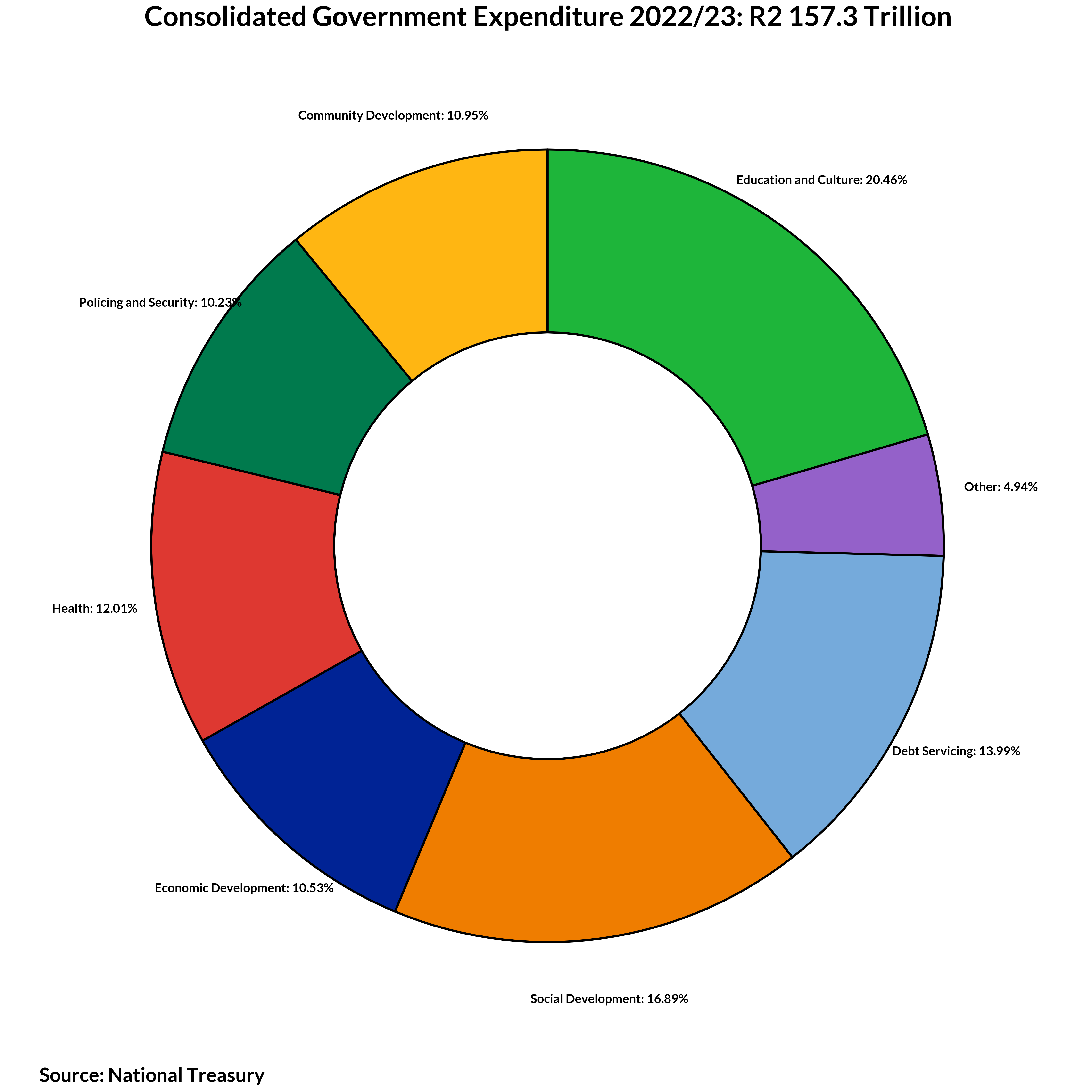

Major problems remain, including growing debt, a shrinking tax base, growing unemployment and a growing public sector wage bill. These problems were either not addressed at all, or tackled without sufficient vigour.

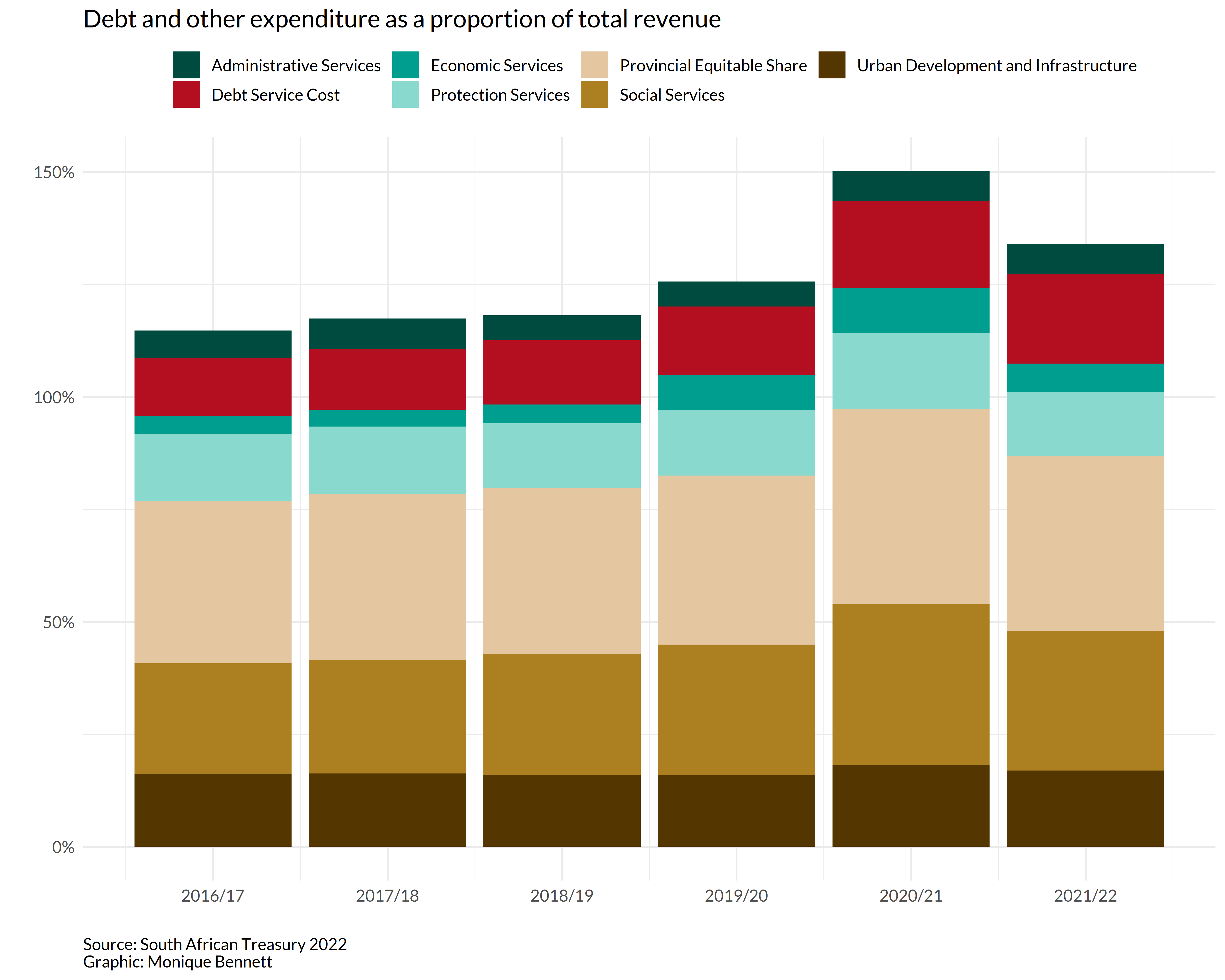

First, the debt burden is more severe than many realise. Ballooning debt servicing requires radical surgery. Recent high commodity prices are temporary and should never be banked on in the long term; the anaemic economic growth expected next year is driven disproportionately by government expenditure and high commodity price forecasts. This is unproductive growth incapable of absorbing labour.

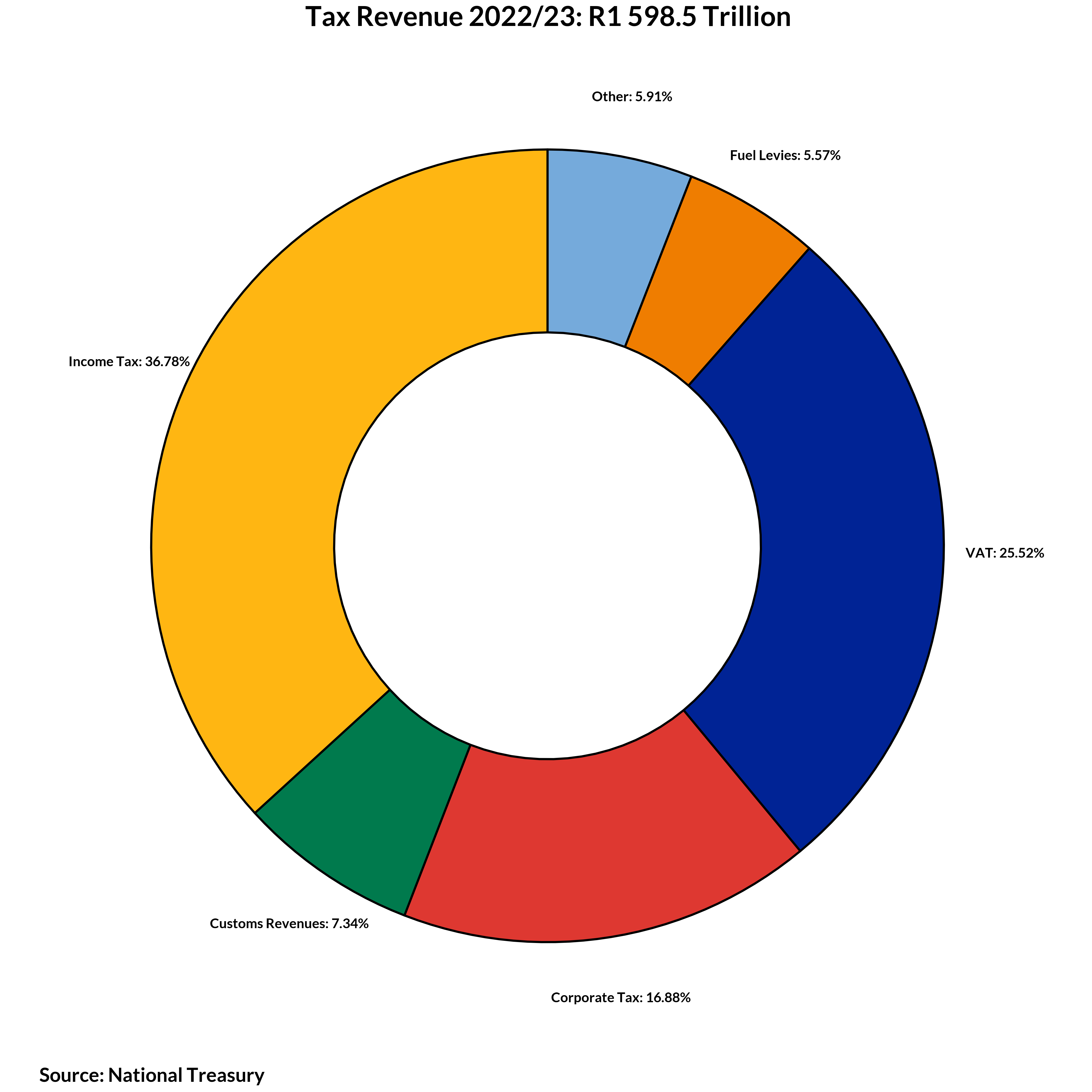

Second, the shrinking tax base is a time bomb. A tiny volume of taxpayers supports growing welfare expenditure without any practicable strategic growth plan. The only viable approach in this respect would be to enable businesses to create jobs. The sole focus on this in the speech related to increased expenditure on infrastructure, reflecting an obsession with government-created employment.

Third, growing unemployment is a calamity that we can’t skirt around any longer. It is worth noting that the official unemployment rate already exceeds the worst unemployment rate (around 33%) registered by any country during the Great Depression of 1929-1934. The unemployment rate of young people, meanwhile, approaching 70%, is more than double that.

Minister Enoch Godongwana addressing the media at the Imbizo Media Centre in Cape Town ahead of the 2022 Budget Speech. (Photos: GCIS)

If the president and the finance minister seriously want the private sector to create jobs, there has to be an urgent and clear plan to remove red tape and create an enabling environment for business. Finances must also be allocated for enterprise development rather than thrown aimlessly at education without substantive returns. Where was the follow-up on the president’s promises that the government would enable business, which would create jobs?

Fourth, the public sector wage bill increase will never settle at an average of 1.8% per annum for the next three years. As a proportion of the budget and relative to the shrinking tax base, the wage bill is cancerous. Despite opposition from the unions and elsewhere, it must be seriously reviewed.

Fifth, Godongwana’s speech gave scant attention to the unprecedented challenge of climate change and South Africa’s commitment to lower carbon emissions. While Eskom’s debt situation received a significant amount of attention, little detail was given as to how to bridge the current energy supply gap, the slow development of renewables, or timelines for retiring coal plants.

Finally, wasteful expenditure due to corruption and incompetence undermines investment potential and destroys the infrastructure on which basic service delivery and economic growth depends. Without functional water and sanitation, for instance, people will die.

How can we stand idly by and watch this unfold? Key corruption watchdog institutions such as the Auditor General and the National Prosecuting Authority must be strengthened. The paltry R1.1 billion increase for the Department of Justice hardly seems sufficient to sustain a prosecutorial campaign against the rampant criminality besetting the state.

How can we stand idly by and watch this unfold? Key corruption watchdog institutions such as the Auditor General and the National Prosecuting Authority must be strengthened. The paltry R1.1 billion increase for the Department of Justice hardly seems sufficient to sustain a prosecutorial campaign against the rampant criminality besetting the state.

Good Governance Africa calls for a stronger focus on the real governance risks that confront us as a country. We encourage an active citizenry that will hold the state to account for its failure to deliver a better life for all.

[activecampaign form=1]