Recommendations to the Zimbabwean government

- Commit to a new, inclusive pathway for a mediated, citizen-centred national dialogue to align with and enact the principles set out in the Zimbabwe Constitution of 2013, to resolve the current constitutional crisis and legitimacy question. Comprehensive legal, political, and economic reform is critical.

- Commit to the drafting and passing of a comprehensive electoral law consistent with the 2013 Constitution that guarantees the independence of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC), allows for the appointment of an independent ZEC chair from outside of Zimbabwe, and prevents government from interfering with the work of the commission.

- Ensure a comprehensive delimitation exercise, extend the voter registration process, and ensure there is a transparent and comprehensive verification process to develop a credible voters’ roll. This would include allowing independent interested stakeholders from civil society, the media, and opposition parties access to inspect the voters’ roll prior to elections.

- Promote a free and fair election campaign environment for all players, and actively guard against voter intimidation by establishing a special body to investigate complaints of political violence and allow external independent observers early access to all voting stations prior to election day.

- Restore independence and citizen trust in the county’s public institutions through, for example, the institution of an independent and impartial judicial committee tasked with restoring judicial independence and making recommendations for complete judicial reform, to eradicate judicial corruption, ensure the independence of judges and improve the functioning of the courts.

- End partisanship in the police force, starting with undertaking investigations into allegations of human rights violations against the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) and other security sector agencies, and ensuring those responsible for such abuses are held accountable under the law.

Introduction

On March 16, 2013, following a nationwide referendum which saw a turnout of more than half of those eligible to vote (3.3 million), a new draft constitution for Zimbabwe was approved by an overwhelming majority (95%) of participants.

The document provided a progressive new framework for how Zimbabwe should be governed. It cites respect for the “supremacy of the Constitution”[1] and “the rule of law” [2] among its founding principles and cornerstone values of a democracy, and contains strong provisions relating to media freedoms[3]; the separation of, and limits on, power[4]; the independence of the courts and judiciary[5]; the devolution of power down to the provincial level[6]; and how and when elections should be run.

Many of the major challenges facing Zimbabwe today would likely be resolved if the 2013 Constitution, which has the support and consensus of the Zimbabwean people, was effectively enacted. However, over the last eight years, Zimbabwe’s government has failed to develop or bring into alignment subsidiary legislation to enact the progressive principles enshrined in the constitution and even passed legislation clearly designed to undermine or reverse them.

On coming to power in 2017, Emmerson Mnangagwa, in his inaugural address as president, hailed a “new beginning” for the country, whereby “the Republic of Zimbabwe renews itself by a government who will work towards ensuring that the pillars of democracy in our land are strengthened and respected.”[7] However, under his tenure, Mnangagwa has deepened Zimbabwe African National Union—Patriotic Front’s (ZANU-PF) disregard for constitutionalism and accelerated the party’s systematic efforts to capture or undermine key rule of law institutions.

The Mnangagwa regime has compromised the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and public prosecutors, packed the courts with loyalists, and harassed and imprisoned dissenting voices. It has transformed the country’s police and military into openly partisan and largely unaccountable arms of the ruling coalition, thus limiting horizontal accountability and consolidating a limited access order for a small politico-military elite.[8]

Since November 2017, the arrest and intimidation of opposition figures and media members has become commonplace. Incidents of gross human rights violations are rarely investigated. Constitutional amendments clearly designed to retain or entrench power of the executive and undermine the opposition are routinely pushed through, with limited citizen participation or any meaningful consultative oversight.[9]

Over the last year, Good Governance Africa (GGA) has held a series of thematic discussions on the current political and economic crisis facing Zimbabwe, the implications of which negatively affect not just the nation’s citizens but the wider southern Africa region. This policy briefing presents some of the key insights and takeaways from engagements with a range of stakeholders from Zimbabwe’s government, civil society and academia pertaining to constitutionalism and the rule of law. Its objectives are to:

- Provide a brief definition of the concepts of constitutionalism and the rule of law.

- Highlight key violations of these principles under the Mnangagwa regime.

- Provide recommendations for building constitutionalism and rule of law in Zimbabwe.

Defining constitutionalism and the rule of law

Constitutionalism and the rule of law are two interrelated ideas sometimes used interchangeably. However, generally speaking, constitutionalism as defined by legal philosopher Wil Waluchow is the idea that “government can and should be legally limited in its powers, and that its authority or legitimacy depends on its observing these limitations”.[10] This includes constitutional devices and procedures such as the separation of powers between the legislature, executive, and judiciary; due process for those charged with criminal offences; the respect for individual rights; among others, usually enshrined in a written constitution.

There are a range of literatures on the rule of law and how it arises, and several rule-of-law indices have emerged in policy literature used to assess country and institutional performance.[11] The World Justice Project, for example, defines rule of law as a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment that delivers:

- Accountability – The government as well as private actors are accountable under the law.

- Just laws – The laws are clear, publicised, stable and fair, protect fundamental rights, including security of persons and property.

- Open government – The process by which laws are enacted, administered, and enforced is accessible, fair and efficient.

- Accessible justice – The laws are upheld, and access to justice is provided by competent, independent, and ethical law enforcement officials, attorneys or representatives, and judges who are sufficient in number, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.

Why are these important?

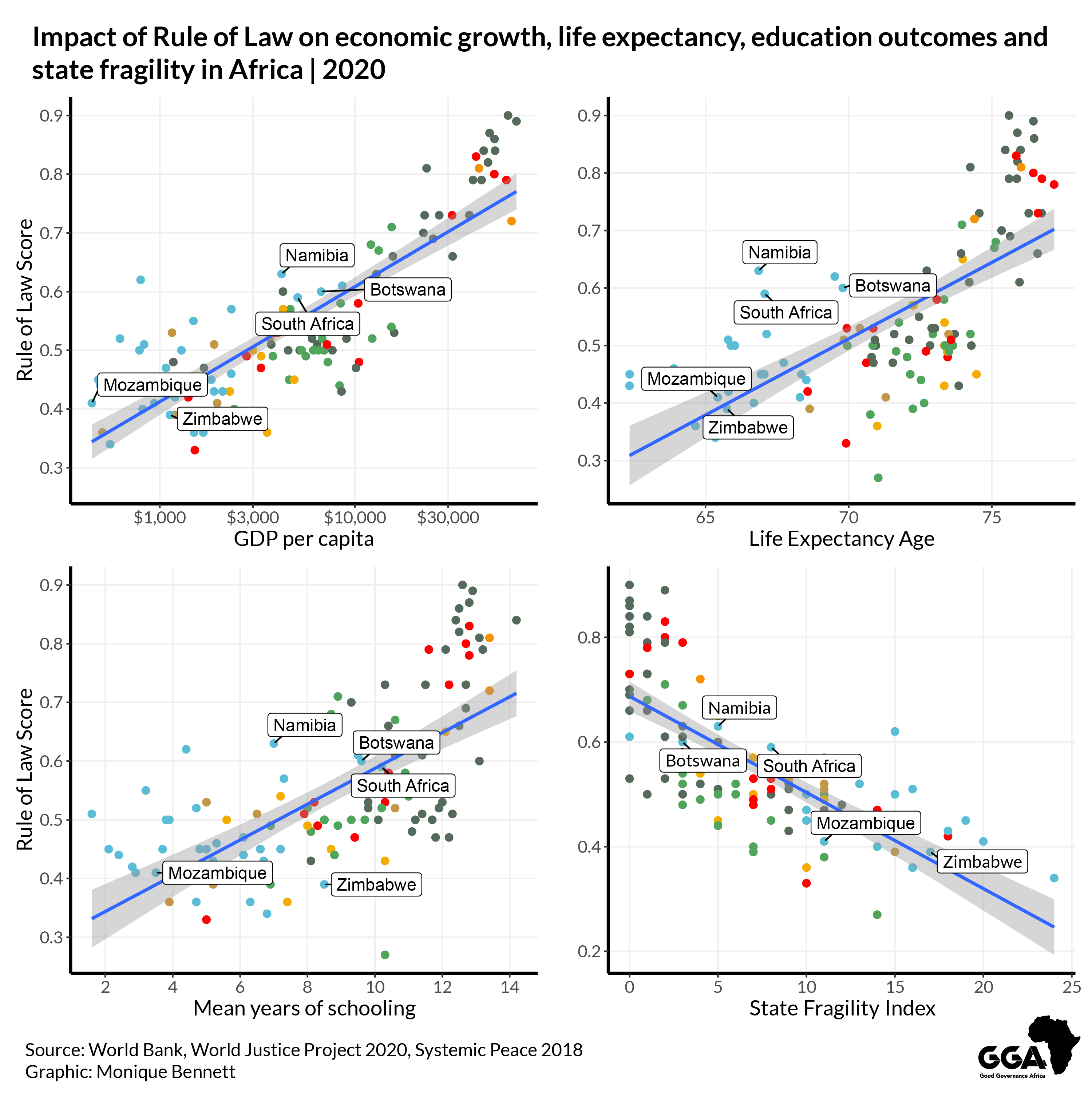

Constitutionalism and respect for the rule of law are fundamental to good governance and the building of fair and equitable societies. Accordingly, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance lists amongst its primary objectives to “promote and enhance adherence to the principle of the rule of law premised upon the respect for, and the supremacy of, the Constitution and constitutional order in the political arrangements of the State Parties.”[12] Moreover, research shows that adherence to the rule of law strongly correlates with higher economic growth, greater peace, less inequality, improved health outcomes and more education. It is, evidently, a prerequisite for building a peaceful and prosperous future for Africa.

How the Mnangagwa regime violates key principles of constitutionalism and rule of law

Renowned legal scholar Louis Henkin identifies several key principles of constitutionalism and rule of law, including:

- Popular sovereignty.

- The supremacy of the Constitution and rule of law.

- Political democracy.

- Separation of power.

- Civilian control of the military force.

- Police governed by law and judicial control.

- An independent judiciary.[13]

The following section provides examples of violations against these principles, all of which are enshrined in the Zimbabwean Constitution. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list, but rather captures key issues highlighted during discussions.

Popular sovereignty

At the core of constitutionalism is the principle of popular sovereignty: that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, through their elected representatives.[14] This principle is recognised in Zimbabwe’s constitution which undertakes to respect global standards of democratic systems, and in its founding values and principles calls for multipartyism; regular, free and fair elections; and the orderly transition of power.[15]

Mnangagwa’s assent to the presidency, by military coup in 2017, followed by a widely disputed 2018 election, marred by allegations[16] of vote rigging, intimidation of the opposition, gerrymandering of constituencies and other abuses, is in direct contravention of the country’s constitution and antithetical to the principle of popular sovereignty. This crisis of legitimacy at the core of the Mnangagwa regime remains unresolved. Studies show that coup governments rarely usher in democracy.[17] Rather, new authoritarian regimes emerge which practise higher levels of state-sanctioned violence.[18] This has become the case in Zimbabwe, where the Mnangagwa regime has shown an increasing willingness to use violence as a means of consolidating power for a political and military elite. This legitimacy crisis can only be resolved through a free and fair election, failing which it will continue to pose serious challenges to rebuilding constitutionalism and rule of law in Zimbabwe.[19] However, given the low likelihood that the ZANU-PF would be willing or able to undertake the necessary reforms that would allow for a truly free and fair election to take place (and which could lead to the party losing power), Zimbabwean academic Dr Ibbo Mandaza argues that a new national conference on Zimbabwe initiated at the national level, but facilitated by regional actors and scaffolded by members of the international community, is necessary.[20]

The supremacy of the constitution and rule of law

Good rule of law requires that the status of any given law be clear, publicised and stable. Similarly, laws should protect fundamental rights, including the security of persons and property, and be formulated and administered in accordance with the spirit of the constitution.[21]

Zimbabwean scholars Hofisi and Masunungure (2020) argue that the phenomenon of rule by law rather than rule of law has become a defining feature of post-independence governance in Zimbabwe, stating that… “whenever the country’s constitution was deemed to be a hindrance to the maintenance and exercise of power it was amended”.[22] Similarly, in a critique of the key legislative framework guiding civil liberties in Zimbabwe, scholars Mapuva and Mapuva-Muyengwa argue the enactment of legislation by ruling elites to restrict the political landscape[23] in their favour has been ongoing for decades, and cite the NGO Bill (2004), Private Voluntary Organisations (1996), Urban Councils Act (1996), Public Order and Security Act (2002), Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (2005), and the Interception of Communications Act (2007), among others, as examples.[24]

More recent examples include the Constitutional Amendment Act No.2, 2019, which came into effect on 07 May 2021 and has been criticised for weakening democracy and “the promotion and protection of human rights in Zimbabwe, particularly those of a civil and political nature.”[25] Current Bills in passage through the National Assembly which will be directly or indirectly used to shrink the country’s democratic space include the Patriotic Bill, which a consortium of civil society organisations in Zimbabwe have stated “serves a single purpose, which is to criminalise free speech, and ultimately control, intimidate and stifle citizens’ democratic rights and fundamental freedoms as enshrined in the Zimbabwe Constitution Chapter 4 Bill of Rights”.[26] Similarly, the Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill, whose Clause 164C criminalises the spread of what the government classifies as “false information online”, punishable with a jail term of up to five years, has been criticised by Transparency International and others as an attempt to obstruct the role of civil society and the media.[27]

Political democracy

According to both the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index and the Varieties of Democracy Index, which measure democratic attributes within a state such as citizens’ ability to influence the political process, Zimbabwe has made slight improvements since 2007 in terms of democratisation, particularly in terms of freedom of expression. However, since coming to power in 2017, despite promises of democratic reform, President Mnangagwa’s regime has launched a crackdown on political opposition to ensure complete and continued control over the nation.[28] This has included widespread voter intimidation[29] and the arrest and torture of opposition supporters.[30] There has also been systematic decimation of the opposition MDC-Alliance through the unconstitutional recall of its MPs to make way for a pliant opposition, the MDC-T.[31] In this bid to ensure a two-thirds majority in parliament, this unconstitutional move has disenfranchised more than a million MDC-Alliance voters from the 2018 election.[32]

Separation of powers?

Governance based on the doctrine of separation of powers between the executive, judiciary, and legislature safeguards a nation against abuse of power by rulers who may want to pursue their own interests at the expense of those they govern.[33]

The Mnangagwa regime has used various strategies to advance a process of authoritarian consolidation and dissolve the separation of powers between branches of government. Opposition legislators have been expelled from parliament, allowing ZANU-PF majority control of the house of assembly. This has enabled the passing of legislation with little to no resistance. This has included, for example, the passing of legislation such as the Constitutional Amendment Act No.2 which amends 27 provisions within the constitution, centralises power in the executive and expands the powers of appointment of judges. In terms of the independence of the judiciary, various reports have shown judges and judicial officers being coerced or bribed to ensure favourable rulings for ZANU-PF affiliates and even sitting magistrates expressing public support for ZANU-PF and seeking to stand for local elections in contravention of the constitution.[34]

Civilian Control of the Military force

The unconstitutional November 2017 military-assisted coup, which installed President Mnangagwa, represents the further evolution of Zimbabwe’s military establishment into an autonomous political actor operating almost completely outside of any civilian control, despite constitutional obligations to remain apolitical.[35] The militarisation of politics in Zimbabwe is not new, dating back to the liberation struggle and worsening throughout Mugabe’s tenure, as ZANU-PF increasingly came to rely on the military establishment to ensure its survival. However, some scholars, such as retired Zimbabwean army lieutenant and Zimbabwean scholar Professor Martin Rupiya, have noted a semblance of professionalism in the military in the country’s early years of independence where the military were largely confined to the barracks.[36]

Over time, the use of the military as a political tool to intimidate and vanquish opponents, enable looting, and gain control of key economic sectors has transformed the country into a military dictatorship.[37] The dominant role the military plays in Zimbabwe’s politics is most clearly demonstrated by the November 2017 coup, which was triggered by Mugabe’s attempt to side-line or fire senior military figures such as army chief Constantino Chiwenga and Emmerson Mnangagwa, as well as the cancellation of a diamond mining contract with Anjin Investments[38] in which the military was a key stakeholder.[39] As Zimbabwean researcher Enock Ndawana (2020) has noted, the departure of President Mugabe is largely due to pressure from the military, which remains the key factor in determining who rules Zimbabwe today.[40] As such, the Zimbabwean military will continue to obstruct efforts to return the country to a state of constitutionalism and rule of law as long as it remains embedded within the country’s political and economic landscape.

Police governed by law and judicial control

The police play a key role in safeguarding the rule of law and maintaining the security of a nation’s citizens. Multiple studies over the past decade have highlighted the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP)’s abandonment of its constitutional mandate in favour of blatantly partisan policing.[41] Under President Mnangagwa, ZANU-PF has continued to transform key rule of law institutions, such as the ZRP, into arms of the party.

Since 2017, the ZRP has frequently been accused of unlawful police action, the intimidation of civilians, human rights activists, the organised legal profession, trade unions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

As Human Rights Watch notes, the human rights situation has continued to decline under Mnangagwa’s presidency.[42] State security agents have frequently been found violating fundamental human rights and freedoms enshrined in chapter 4 of the 2013 Constitution, including committing violent assaults, arbitrary arrests, abductions, and torture against the media, opposition politicians, and citizens deemed “dissidents”.[43]

Notably, in July 2020, police arrested prominent journalist Hopewell Chin’ono and Transform Zimbabwe Party leader Jacob Ngarivhume after they called for nationwide anti-corruption protests.[44] Over the course of 2020, gross human rights violations by state security forces against 70 critics were recorded. There is a general lack of accountability as authorities continually fail to investigate allegations of human rights violations.[45]

An independent judiciary

Section 164 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe specifically entrenches judicial independence and states that courts must apply the law and Constitution “impartially, expeditiously and without fear, favour or prejudice”. However, under the Mnangagwa regime, there is evidence of continued judicial capture and undermining the independence of the courts. Research shows various strategies used by the government to bring the judiciary under its control, including a combination of public attacks, threats and intimidation, and financial inducements to make judges more malleable to the ruling coalition’s aspirations.[46]

In addition, government continues to push through legislation designed to further undermine the independence of the judiciary. The adoption of the Constitutional Amendment No.2, 2019 has been widely criticized as a direct threat to judicial independence. The Bill was unconstitutionally amended and fast tracked through the National Assembly before being enacted and coming into force on 07 May 2021.[47] The Bill gives the executive essentially full discretion in the appointing of judges, after recommendations are received from the Judicial Service Commission, including the appointment of the Prosecutor-General without subjecting him or her to public interviews.[48]

Further to this, the Bill also extends the term limits for judges, allowing them to serve until they are 75 rather than 70 years old. This was widely viewed as an attempt by President Mnangagwa to retain the services of chief justice Luke Malaba (a key Mnangagwa ally and loyalist) who recently turned 70.[49] Following two consolidated urgent applications by Musa Kika, Young Lawyers Association of Zimbabwe (YLAZ) and Fredrick Mutanda, the High Court declared that the extension of tenure was not applicable to the incumbent Chief Justice and other superior court judges, in line with section 328(7) of the Constitution. The court noted that “extending any term limits of public officers prescribed in the Constitution would not apply to anyone currently in office when the amendments came into effect.”[50] While this should be seen as a victory for efforts towards judicial independence, following the ruling, the Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs made public threats against lawyers in civil society and the judiciary and the government of Zimbabwe went on to file two separate appeals in response.[51]

Conclusion

As the above insights have demonstrated, the fundamentals of Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution, a landmark foundation agreed to by the Zimbabwean people and on which a new country was to be built, have been widely violated by the ZANU-PF government. This is a matter of deep local and international concern. All interested actors need to now coalesce around this Constitution and work towards a national settlement that realigns Zimbabwe with the Constitution, and reverses the destructive manipulations that the ruling party has entrenched in the eight years since it was enacted.

[1] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) . Act, 2013. Chapter 1. Section 3a.

[2] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) . Act, 2013. Chapter 1. Section 3b.

[3] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20). Act, 2013. Chapter 4. Section 61 & 62.

[4] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20). Act, 2013. Chapter 1. Section 3.

[5] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20). Act, 2013. Chapter 8. Section 164.

[6] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20). Act, 2013. Chapter 14. Section 264.

[7] Mnangagwa, E. Presidential Inaugural Address. National Sports Stadium, Harare, Zimbabwe. Filmed 24 November 2017. Video of address, 37:27. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6h7L9LilBA

[8] Van Bavel,B., Ansink, E., Van Besouw, B. (2016). Understanding the economics of limited access orders: incentives, organisations and the chronology of developments. Journal of Institutional Economics. Vol 13,1.

[9] See, for example, Veritas’s “Constitution Watch 1/2021” on the fast-tracking of Amendment No. 2. Available http://www.veritaszim.net/node/4929

[10] Waluchow, W. “Constitutionalism”. The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

[11] Hadfield & Weingast (2014) , in a review of rule of law literature, find that most fall into two categories. The first assumes rule of law is the product of governments with an effective monopoly on the legitimate use of force. The second assumes it is indistinguishable from other cultural order-producing process which precede institutions. See: Hadfield, G.K.,Weingast, B.R. (2014). Microfoundations of the Rule of Law. Annual Review of Political Science. 17:21-42. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135226

[12] Organization of African Unity (OAU). African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. (“Banjul Charter”), 27 June 1981.

[13] Henkin, L., (1979). The Rights of Man Today. Routledge: New York. (As cited in Michael Rosenfield ed., Constitutionalism, Identity, Difference and legitimacy, Theoretical Perspectives. Durham: Duke University Press.

[14] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Popular sovereignty”. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 26 Aug. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/popular-sovereignty. Accessed 22 June 2021.

[15] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) . Act, 2013. Chapter 1. Section 3. Sub-Section 2a,2bii,2c.

[16] Transparency International. (2018). 2018 Annual State of Corruption Report (Electoral Integrity in Zimbabwe. https://www.tizim.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/TIZ_2018_AnnualStateofCorruptionReport.pdf

[17] Svolik, M. W. (2014). Which Democracies Will Last? Coups, Incumbent Takeovers, and the Dynamic of Democratic Consolidation. British Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 715–738. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000550

[18] See Derpanopolous, G., Frantz, E., Geddes, B., Wright, J. (2016). “Are coups good for democracy? “Research & Politics. January 2016. doi:10.1177/2053168016630837

[19] Generally speaking, ‘Free’ means that all those entitled to vote have the right to be registered and to vote and must be free to make their choice between party or candidate without fear of reprisal. ‘Fair’ means that all registered political parties and/or candidates have an equal right to contest the elections, campaign for voter support through the holding meetings and rallies. For a detailed account on the processes, principles, and procedures needed to ensure an election is “free and fair” see Elkit, J., Svensson, P. (1997). What Makes Elections Free and Fair? Journal of Democracy. 8(3):32-46. DOI:10.1353/jod.1997.0041

[20] Mandaza, I. (2021). “A Paradigm shift from false expectations of reform in a securocrat state, to a conference to resolve it.” 04 March. https://gga.org/a-paradigm-shift-from-false-expectations-of-reform-in-a-securocrat-state-to-a-conference-to-resolve-it/

[21] World Justice Project. “The Four Universal Principles”. Available https://worldjusticeproject.org/about-us/overview/what-rule-law, Accessed 22 June 2021.

[22] Hofisi, S., Masunugure, E. (2020). “Rule by law or rule of law?” Zimbabwe Governance Report. Good Governance Africa. July 2019. https://gga.org/author/sharon-hofisi-and-eldered-masunungure/ Accessed21 June 2021.

[23] As argued by political scientist Joakim Ekman (2009), in recent decades, several countries have “moved away from outright authoritarianism into regimes that combine democratic and non-democratic characteristics where formally democratic political institutions, such as multiparty elections, mask the reality of authoritarian domination.” From this perspective, rather than solely relying on brute force, Zimbabwe’s political elite have used ostensibly “democratic” institutions, such as the legislature, judiciary, and multiparty elections, to consolidate power while masking a process of authoritarian consolidation. Ekman, J. (2009). Political Participation and Regime Stability: A Framework for Analyzing Hybrid Regimes. International Political Science Review. Vol. 30, No, 1,7-31. www.jstor.org/stable/20445173. Accessed 28 June 2021.

[24] Mapuva, J.,Muyengwa-Mapuva, L. (2012). A Critique of the Key Legislative Framework Guiding Civil Liberties in Zimbabwe. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2012, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2184686

[25] Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition. (2021). Joint Civil Society Statement on the Consitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.2) Bill. The Zimbabwean. Published 29 April. https://www.thezimbabwean.co/2021/04/joint-civil-society-statement-on-the-constitution-of-zimbabwe-amendment-no-2-bill/

[26] Ntali, E. (2021). “Patriotic Bill An Attempt to Silence Civic Space: CSOs. All Africa. April 2021. https://allafrica.com/stories/202104280847.html

[27] Transparency International. (2020). Zimbabwe: Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill Would Restrict Anti-Corruption Watchdogs. 11 September. https://www.transparency.org/en/press/zimbabwe-cyber-security-and-data-protection-bill-would-restrict-anti-corruption-watchdogs-1

[28] Mnangagwa, E. (2018). “Emmerson Mnangagwa: ‘We Are Bringing About the New Zimbabwe.” New York Times. 11 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/11/opinion/zimbabwe-emmerson-mnangagwa.html

[29] Gavin, M., Moss, T. (2018). “Zimbabwe’s Upcoming Election Is a Political Charade.” Foreign Affairs. 25 July. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/zimbabwe/2018-07-25/zimbabwes-upcoming-election-political-charade

[30] Mutsaka, F. (2020). “Zimbabwe continues to arrest critics, says opposition party.”IOL. 03 August. https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/zimbabwe-continues-arrests-of-critics-says-opposition-party-67470535-8302-4faa-bae9-0f0aff2a6cee

[31] In February 2018, Nelson Chamisa took over as Zimbabwe’s main opposition party the Movement for Democratic Change – Tsvangirai, after the death of former leader Morgan Tsvangirai to cancer. This party subsequently became known as the MDC-Alliance (MDC-A). However, beginning in March 2020, the courts began to pave the way for a minor political party, the MDC-T, led by Mnangagwa ally Douglas Mwonzora, to challenge the leadership of the main opposition party, the MDC-A. This culminated in the courts recognising Mwonzora’s group as the legitimate MDC and Chamisa’s party being evicted from the party headquarters by the police. Since then, Mwonzora’s faction has recalled multiple legislators elected on Chamisa’s MDC-A ticket, thereby disenfranchising voters. MDC-T senators have also sided with Zanu-Pf on critical constitutional amendments on the senate flaw thereby helping the ruling party achieve two-thirds majority. See: 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practises: Zimbabwe. US State Department. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/zimbabwe/ Accessed: 27 June 2021.

[32] Mandaza, I. (2021). “Zimbabwe: Stop expecting the impossible – take action at national, regional and international level – now”. Daily Maverick. 08 March. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-03-08-zimbabwe-stop-expecting-the-impossible-take-action-at-national-regional-and-international-level-now/

[33] Fombad, C.M. (2014). Strengthening constitutional order and upholding the rule of law in Central Africa: Reversing the descent towards symbolic constitutionalism. African Human Rights Journal. Vol 2, No.2.,412-448.

[34] See, for example: Transparency International. (2019). 10th edition of the Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) – Africa. https://www.transparency.org/en/gcb/africa/africa-2019 Accessed 27 June 2021 ; Verheul, S. (2021). From ‘Defending Sovereignty’ to ‘Fighting Corruption’: The Political Place of Law in Zimbabwe After November 2017. Journal of Asian and African Studies. Vol 56, 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620986587; Chifamba, M. (2020). “Zimbabwe: Mnangagwa’s capture of judiciary a red flag for state failure.” The Africa Report. 23 November. https://www.theafricareport.com/51602/zimbabwe-mnangagwas-capture-of-judiciary-a-red-flag-for-state-failure/

[35] Nyakanyanga, S., Fabricius, P. (2017) “Zimbabwe: Army in control of state institutions but insists not a coup”. Daily Maverick. 15 November. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-11-15-zimbabwe-army-in-control-of-state-institutions-but-insists-not-a-coup/

[36] Rupiya, M. (2017). “Retired Army Lt, Martin Rupiya reacts to Zimbabwe developments. Youtube. 03:44, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DMCIzH8gQvk

[37] International Crisis Group. (2017). Zimbabwe’s “Military-assisted transition” and Prospects for Recovery. Briefing No 134. 20 December. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/southern-africa/zimbabwe/b134-zimbabwes-military-assisted-transition-and-prospects-recovery

[38] Matimaire, K. (2021). “Zimbabwe: Army-Linked Anjin Grabs Richest Diamon Claim. All Africa. 21 January. https://allafrica.com/stories/202101150292.html

[39] See Beardsworth, N., Cheeseman, N., Tinhu, S. (2019). Zimbabwe: The coup that never was, and the election that could have been. African Affairs. Vol 118, 472, 580-596. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz009

[40] It is important to note that the military in Zimbabwe is not homogenous nor fully united and there exists significant levels of resentment within certain quarters within military ranks at the high levels of corruption of the leadership.

[41] Mugari, I.,Obioha, E.E. (2018). Patterns, Costs, and Implications of Police Abuse to Citizen’s Rights in the Republic of Zimbabwe.” Soc. Sci. 7, no. 7: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7070116

[42] Human Rights Watch. (2020). Zimbabwe: Events of 2020. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/zimbabwe Accessed 21 June 2021.

[43] The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) . Act, 2013. Chapter 4. Part 2.

[44] GGA has provided extensive coverage and analysis on the events preceding and following the #ZimbabweanLivesMatter movement, which can be accessed here: https://gga.org/category/centres/sadc/governance-reports/zimbabwe-governance-report/

[45] See GGA’s extensive coverage of these protests and their outcomes, including Mashingaidze, S. (2020) “#ZimbabweanLivesMatter: Can South Africa get it right this time?” Zimbabwe Governance Report. Good Governance Africa. 16 September. https://gga.org/tag/july-31-citizen-protests/

[46] Mavhinga, D. (2017). “Zimbabwe Constitutional Court May Lose its Independence”. Human Rights Watch. 27 July. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/27/zimbabwe-constitutional-court-may-lose-its-independence

[47] Veritas (2021) “Constitution Watch 1/2021.”Available http://www.veritaszim.net/node/4929 . Accessed 22 June 2021.

[48] Mutlokwa, H. (2021). “A Failed State in the Making: How Zimbabwe’s Constitutional Bill No.2, 2019 constrains judicial independence.07 May. https://verfassungsblog.de/a-failed-state-in-the-making/

[49] Samaita, K. (2021). “Zimbabwe’s judges threatened after failure to extend chief justice’s term”. Business Day. 17 May. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/world/africa/2021-05-17-zimbabwe-minister-threatens-judges-after-failure-to-extend-chief-justices-term/

[50] Southern African Litigation Centre. (2021). “SALC Statement on Judicial Independence, Separation of Powers and the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe.” 20 May. https://www.southernafricalitigationcentre.org/2021/05/20/salc-statement-on-the-judicial-independence-separation-of-powers-and-the-rule-of-law-in-zimbabwe/

[51] Southern African Litigation Centre. (2021). “SALC Statement on Judicial Independence, Separation of Powers and the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe.”

Bibliography

Beardsworth, N., Cheeseman, N., Tinhu, S. (2019). Zimbabwe: The coup that never was, and the election that could have been. African Affairs. Vol 118, 472, 580-596. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz009

Ekman, J. (2009). Political Participation and Regime Stability: A Framework for Analzying Hybrid Regimes. International Political Science Review. Vol. 30, No, 1,7-31. www.jstor.org/stable/20445173. Accessed 28 June 2021.

Elkit, J., Svensson, P. (1997). What Makes Elections Free and Fair?Journal of Democracy. 8(3):32-46. DOI:10.1353/jod.1997.0041

Mandaza, I. (2021). “A Paradigm shift from false expectations of reform in a securocrat state, to a conference to resolve it.” 04 March. https://gga.org/a-paradigm-shift-from-false-expectations-of-reform-in-a-securocrat-state-to-a-conference-to-resolve-it/

Mandaza, I. (2016). Zimbabwe in transition: the political economy of the state in Zimbabwe: the rise and fall of the securocrat state. SAPES Trust. Monograph series, no. 25. https://www.worldcat.org/title/zimbabwe-in-transition-the-political-economy-of-the-state-in-zimbabwe-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-securocrat-state/oclc/991584164

Hadfield, G.K.,Weingast, B.R. (2014). Microfoundations of the Rule of Law. Annual Review of Political Science. 17:21-42. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135226