October 11 is the United Nations International Day of the Girl Child, a day to commemorate young women and girls globally and highlight the obstacles they face in fulfilling their potential. As part of the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) plan of action for people, planet and prosperity, the UN identifies four priorities: social security; education, health and nutrition; gender equality; and youth empowerment. Similarly, the African Union’s Agenda 2063 has put in place a strategic framework that targets inclusive and sustainable development.

Africa is home to about 308 million young women and girls, who constitute a crucial part of the continent’s population, according to the African Child Policy Forum’s (ACPF) 2020 ‘African Report on Child Wellbeing’. According to World Bank population data, African girls between the ages of 0 to 19 account for roughly 52% of the region’s total female population in sub-Saharan Africa. These numbers are especially concerning when noting projections from UN Women, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Pardee Center for International Futures, which indicate that about 62.8% of the world’s women and girls living in extreme poverty are found in sub-Saharan Africa as of 2022.

But the broad lack of human rights and the daily challenges that African girl children face continue to be negated, and fall to the periphery of policymaking and budgetary focus. As the ACPF report notes, ultimately, social and cultural attitudes and beliefs inform norms that define opportunities like access to education and healthcare, nutrition, security, economic opportunity and even how young women and girls spend their time. Thus, conventional laws and policies, preferential social norms and practices determine the quality of life of young women and girls at every stage of their lives and require deep interrogation.

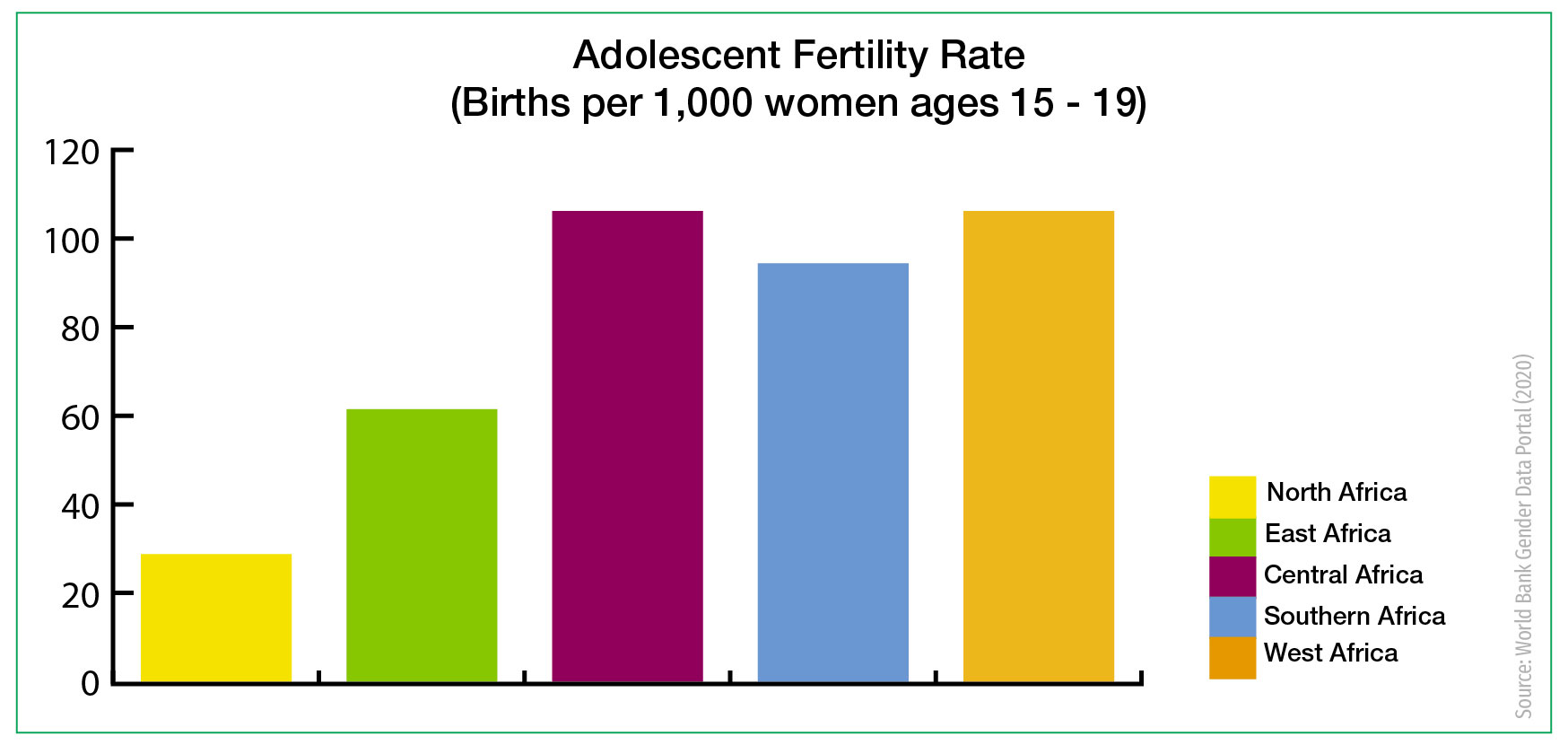

Figure 1: Adolescent fertility rate

And while African governments and international human rights organisations recognise the value of African women and girls to society, and their commitment to improving gender equality has resulted in efforts toward bridging key access gaps, the realities that girl children on the continent face continue to demand greater prioritisation.

For a start, adolescent marriage, pregnancy and the health of newborns remain pertinent issues across the continent, while high fertility rates among adolescent girls continue to pose a developmental challenge.

According to data from the World Bank’s Gender Data Portal and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF’s) ‘State of the World’s Children’ 2021 report, West Africa and central Africa have the highest rates (more than 1,050 births per 1,000 women and girls aged 15 to 19), followed by southern Africa (Fig 1), which has an average of 940 births per 1,000 women and girls of the same age group. East Africa follows with 610 births (per 1,000 women and girls aged 15 to 19) and, last, North Africa with 280 births per 1,000 women.

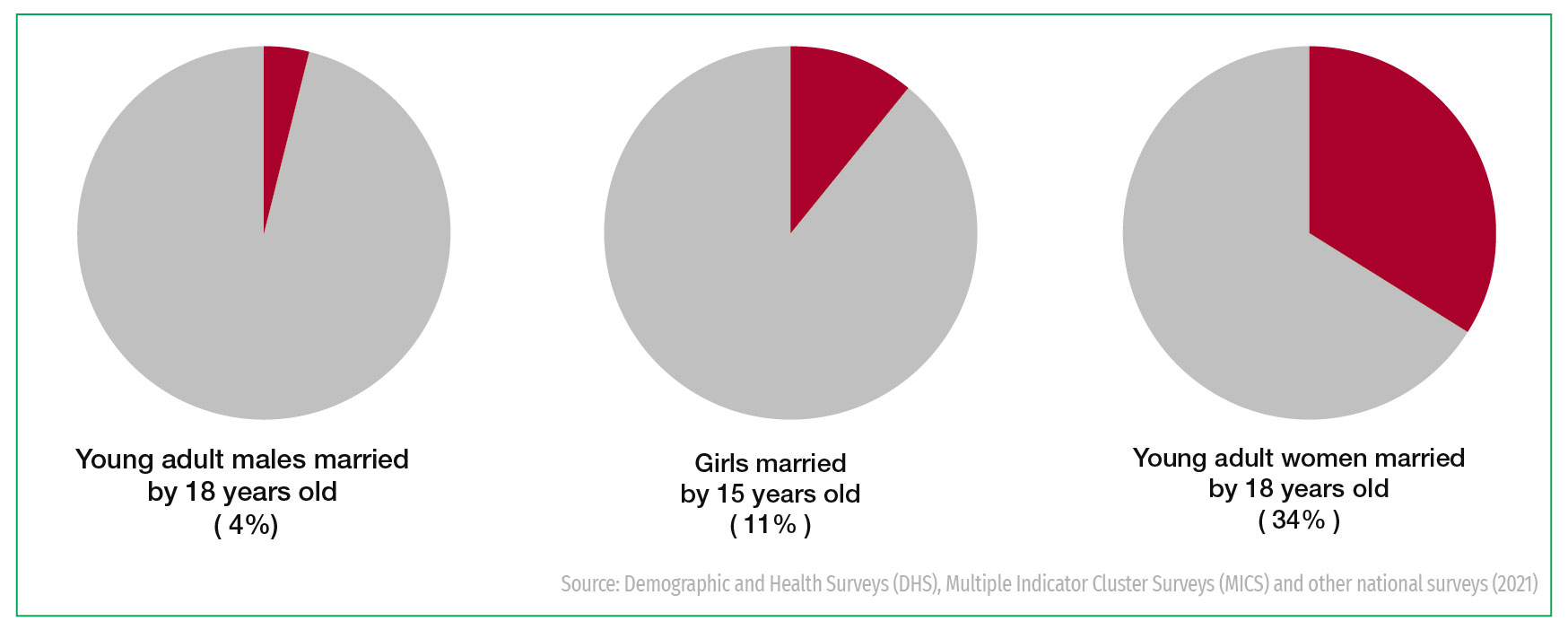

Figure 2: Child marriage

Adolescent pregnancy occurs most frequently in Niger (with an adolescent fertility rate of 177.46%) followed by Mali (with 162.35%), Chad (151.56%), Equatorial Guinea (149.11%), and Angola (142.82%). These high adolescent fertility rates indicate the increased likelihood that these young African women and girls will give birth more than once during adolescence. Subsequently, they correspond with regional averages of child marriages, which also remain high across the continent. The central African region records the highest incidence of child marriage, followed by West African countries (Fig 2). In Niger, 76% of women aged 20 to 24 years old are married or were in a union before they were 18 years old, followed by the Central African Republic (CAR) and Chad with 61%, and Mali with 54%.

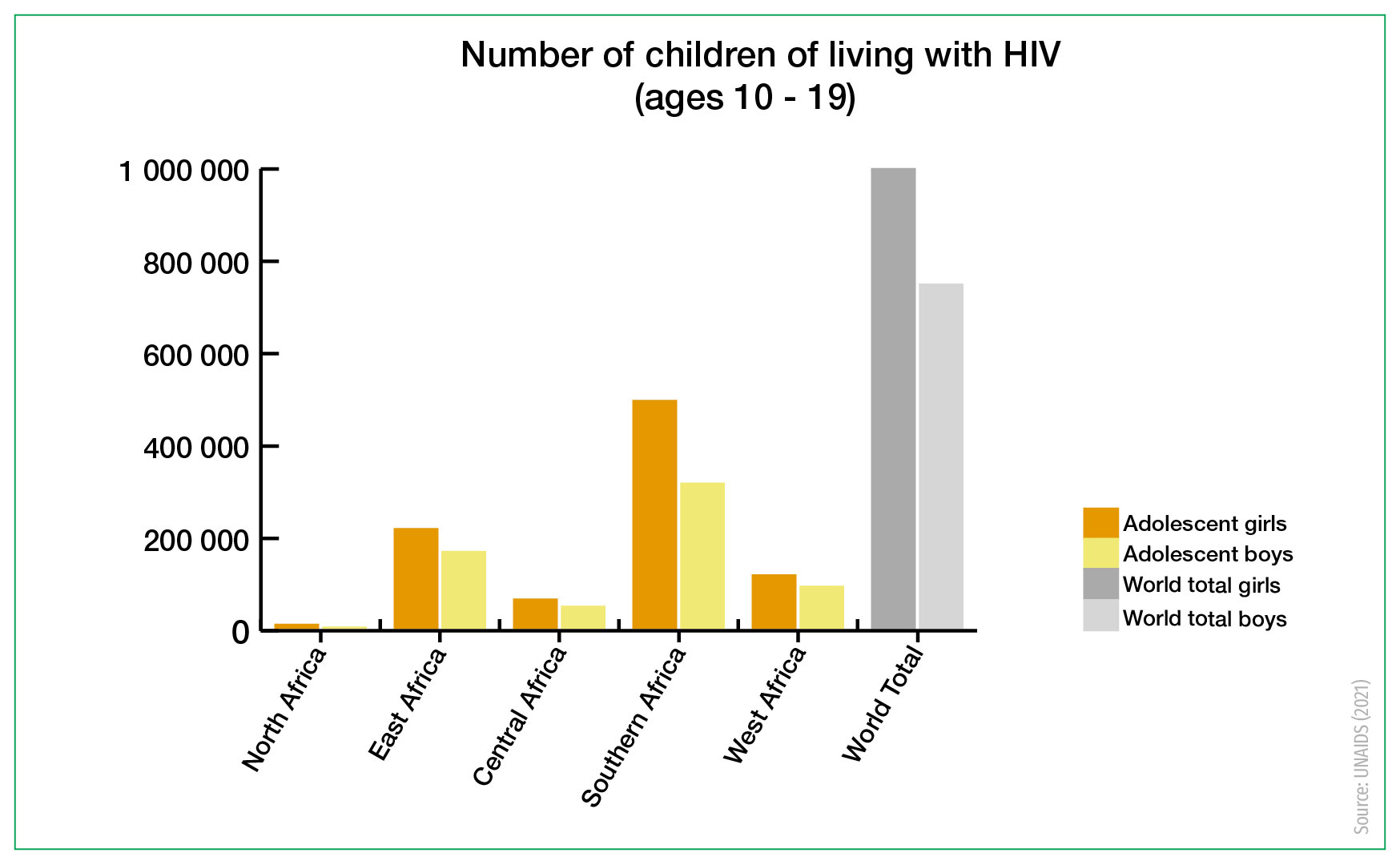

The numbers also reveal that Africa’s adolescent girls have a higher risk of sexual and reproductive health complications and are more likely to be excluded from or have access to healthcare. According to World Bank and UNICEF data, there are more African girls living with HIV than boys across the continent (Fig 3). Three in every five new HIV infections among 15-19-year-olds are young women and girls. Moreover, seven in every 10 adolescent girls do not have comprehensive knowledge about HIV and reproductive healthcare, placing them at greater risk of victimisation due to a lack of education.

Figure 3: Children living with HIV

Southern Africa remains the region with the highest number of infected adolescent girls, followed by East Africa, West Africa, and, lastly, central Africa. The prevalence of HIV-infected adolescent girls remains highest in South Africa, with an estimated 230,000 girls living with HIV, followed by Mozambique, where there are an estimated 82,000 girls living with HIV.

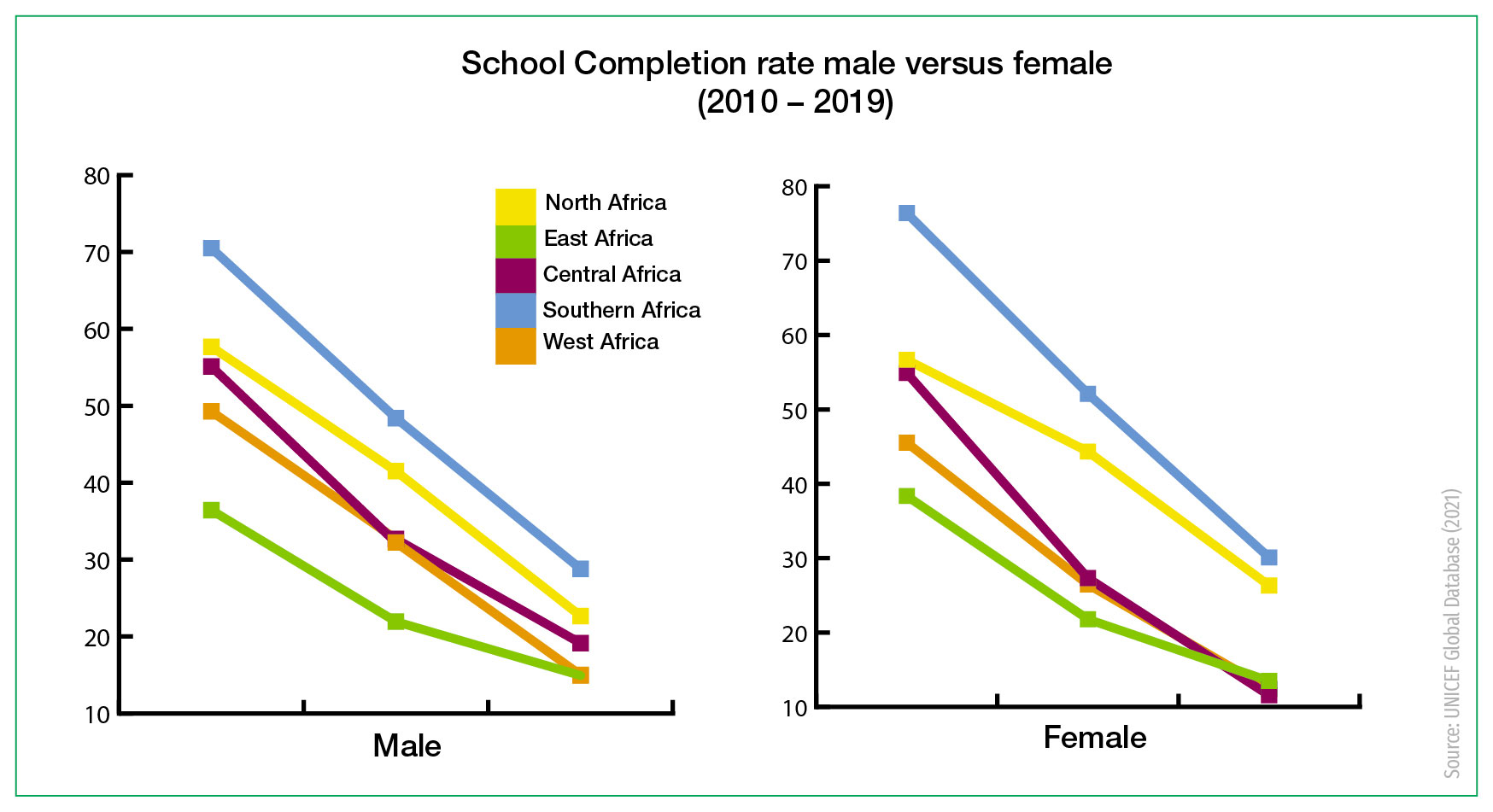

Africa’s young women and girls are also less likely to complete school, according to the data, and are more likely to spend most of their time engaged in unpaid domestic work when compared to their male counterparts. Inequitable access to schooling disproportionately affects girl children at all stages of education. Out-of-school rates for adolescent girls of primary school-going age remain high, and are above world averages in East Africa, central Africa, and West Africa. In particular, more than 50% of young women and girls in Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, and South Sudan are out of school at primary level (Fig 4).

Figure 4: School completion rates

By upper secondary schooling level, there is a drastic increase in out-of-school rates across all regions of the continent. North Africa is the only region to report an out-of-school rate of less than 20% by upper secondary level. When it gets to upper secondary schooling level, Chad (85%), Ethiopia (75%), Guinea (76%), Malawi (76%), Mali (79%), Niger (89%), and Tanzania (88%) all record out-of-school rates above 75% for adolescent girls. Similarly, school completion rates for East Africa, central Africa, and West Africa show significant decreases in adolescent girls between primary and secondary levels.

Social roles and gender norms also place a greater burden on young women and girls, making them less likely to pursue individual interests, education, and career goals. Domestic work and household chores are largely considered a woman’s responsibility and girl children are tasked with either fulfilling it (in the case where the mother is absent or unable to) or helping the older women fulfil these roles. These attitudes and expectations reveal an added disadvantage that adolescent girls in Africa face. Adolescent girls engage in three times more domestic work than their male counterparts, leaving them with less time to focus on their schooling and placing them at greater risk of domestic and sexual violence and health consequences.

Across the continent, the prevalence of violent discipline in childhood remains high – a critical issue regardless of gender. Benin (91%), CAR (90%), Egypt (93%), Ghana (94%), Liberia (90%), and Togo (92%) have the highest rates of violent discipline (including psychological aggression) experienced by children aged 1-14 years by close family members or teachers, UNICEF ‘State of the World’s Children’ (SOWC) data indicates. Moreover, while both young boys and girls are exposed to violent discipline, young women and girls are disproportionally at risk of exposure to sexual violence before they turn 18. Young women and girls are 10 times more likely to experience sexual violence at home or school in childhood in Rwanda, roughly four times more likely to experience sexual violence at home or school in Uganda, and two times more likely to experience sexual violence at home or school in Kenya and Mozambique when compared to their male counterparts in similar environments.

For young women and girls who live in poverty and who do not have access to sufficient and safe infrastructure, the consequences of this burden of domestic work have serious implications on their health and security. Aside from the demand on and threat to their physical health and safety (for example their safety when having to walk far distances to fetch water or smoke inhalation when cooking around open flames), the psychological and emotional burden, exposure to household and sexual violence and their inability to protect themselves significantly impacts their mental health. The ACPF reports that young women and girls exposed to multiple forms of violence are between two and seven times more likely to experience mental illness when compared to those young women and girls who are not exposed to violence in the home or school.

Despite the sobering realities of the lived experiences and challenges faced by young African women and girls outlined here, the commitments of African governments to improving the health and well-being of its 308 million girls remain in opposition to the norms, attitudes, and practices that permeate social and cultural spaces. As the ACPF makes clear, the exclusion of young women and girls from key decisions about their healthcare, schooling, priorities, and interests, and the low investment in securing child protection by many African governments remains a key barrier to achieving the inclusive and sustainable development set out in both the AU’s Agenda 2063 and the UN’s SDGs 2030.

Achieving greater participation and recognition of the autonomy of young African women and girls demands that the confrontation of patriarchal and cultural gender norms, which ultimately limit girls’ engagement in matters relevant to their everyday lives, must be intensified. For African governments’ commitment to sustainable and inclusive development to be actualised, societies need to place a greater emphasis on centralising and listening to our young African women and girls.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.