What do young people in Africa find acceptable when it comes to health and social interventions? This should be a key question of interest for policymakers, intervention developers, and service providers concerned with the well-being of this population and the continent.

Africa can be considered the world’s youngest continent, as young people under the age of 25 account for almost 60% of its population. These young people have the potential to thrive and contribute positively to future African societies and economies. But many face considerable health and developmental challenges, such as unemployment, poverty, environmental stressors, exposure to violence, COVID-19 and other health challenges, and poor access to healthcare.

This also has a gender dimension since young women and girls are often disproportionately affected by these challenges, with the recent Covid-19 pandemic having worsened these gender inequalities, as argued by Bright Opoku Ahinkorah and colleagues in their recent article, ‘Pandemic Worsening Gender Inequalities for women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa’. If we are to come close to achieving Africa’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and meeting the Africa Agenda 2063 vision, we will need to develop and scale up more effective health, education, and economic interventions and services, that are suited to the needs of adolescents and youth.

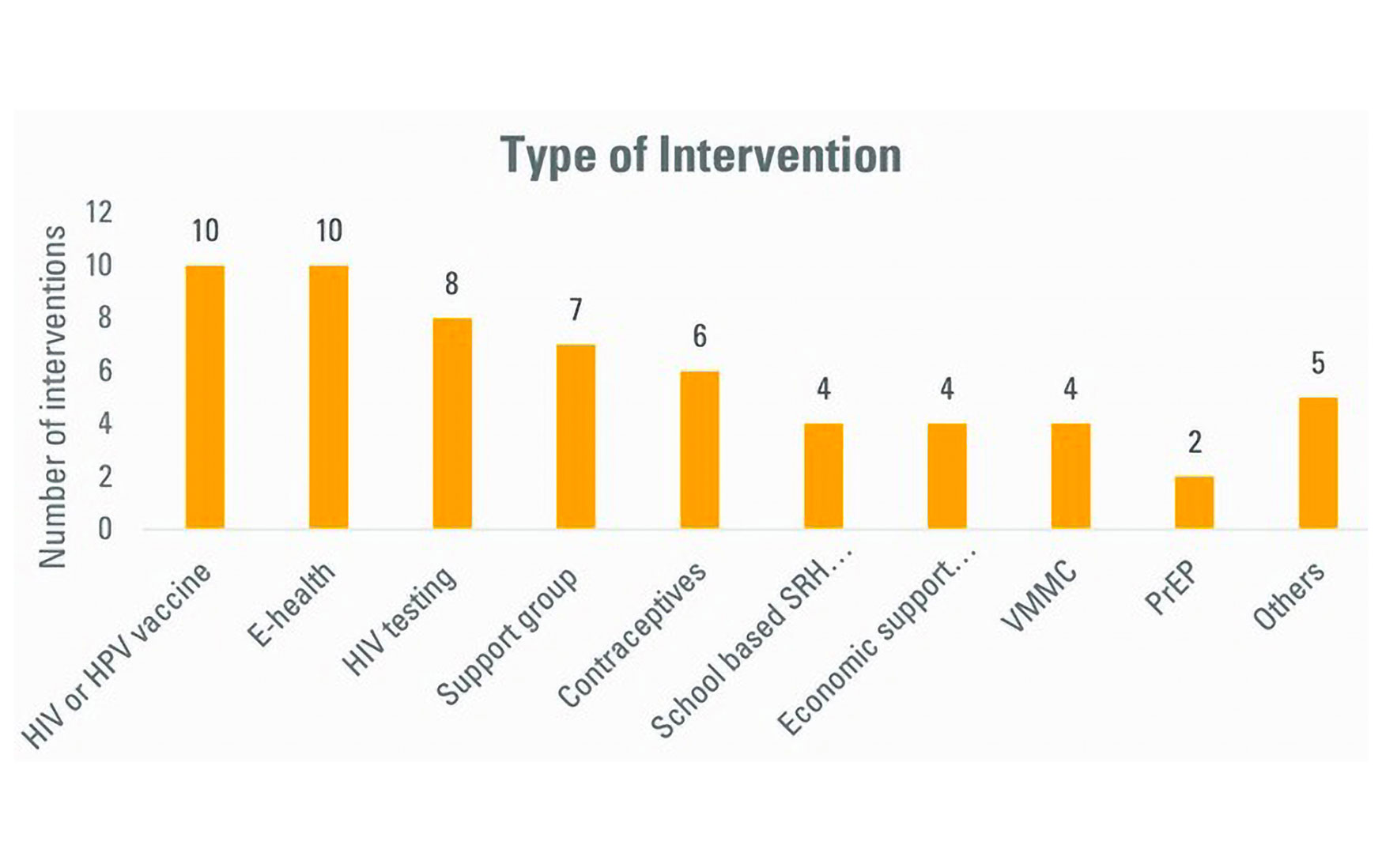

Figure 1: Types and numbers of interventions assessed for acceptability with young people in Africa (2010-2020). Figure taken from: Somefun OD, Casale M, Haupt Ronnie G, et al. Decade of research into the acceptability of interventions aimed at improving adolescent and youth health and social outcomes in Africa: a systematic review and evidence map BMJ Open 2021;11: e055160

But making services and interventions available is only half the battle won. It will also be important for young people to find these interventions acceptable so that they will choose to access or participate in them, and not drop out once they do. Interventions that young people find appropriate, based on how they feel and what they think about these, are simply more likely to be taken up and to work. This too may have a gender dimension as what may be acceptable to young men versus young women could differ.

So, what do African adolescents and youth find acceptable? When I and colleagues working in an international adolescent research hub in 2020-21, looked to the literature to answer this question, we realised that there wasn’t much research about this in Africa. There also weren’t any sources aggregating findings from studies across the continent. So, we systematically reviewed all studies conducted in Africa and published over the past decade (2010-2020), that assessed the acceptability of interventions with adolescents and youth aged 10-24. We included all types of interventions that aimed to improve outcomes outlined in the SDGs.

As we describe in a recently published mapping review paper, we found 55 studies evaluating 60 interventions for acceptability. Most of these studies were carried out in southern and East Africa, mainly South Africa and Uganda. Most were linked to SDG goal 3, ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being, and the majority focused on HIV and sexual and reproductive health (SRH).

Based on their mode of delivery, 10 interventions could be categorised as HIV or HPV vaccine interventions, 10 as e-health interventions, eight as HIV testing interventions, seven as support group interventions, and six as contraceptive interventions (see the diagram below). There were also programmes for voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

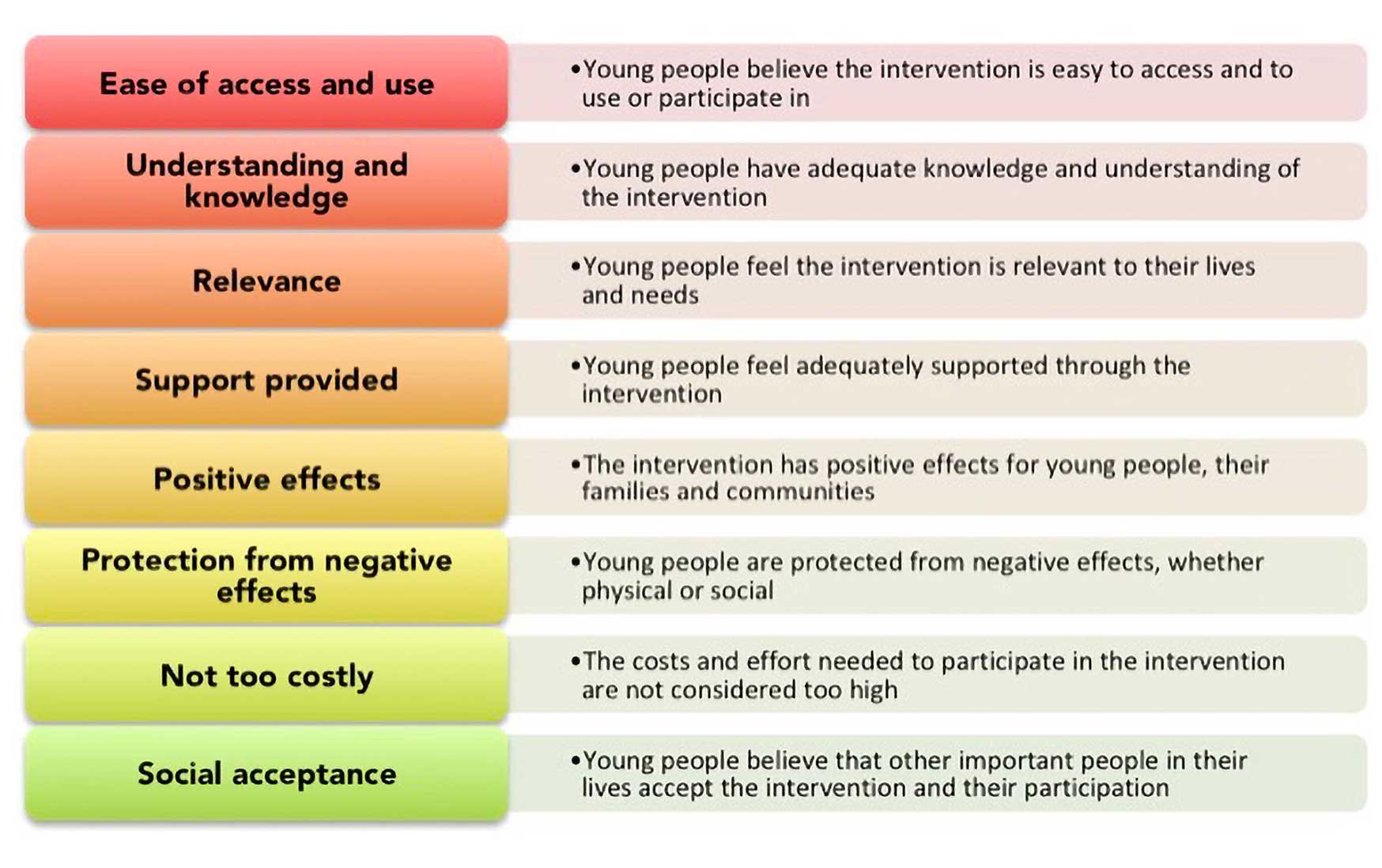

Figure 2: The diagram above highlights the reasons most frequently provided by young people to explain why they found these (mainly SRH) interventions acceptable or not, as described further in our review paper.

Young people needed to feel that the available products and programmes would be easy for them to access and use, for example in the case of injectable contraceptives or contraceptives available in school-based clinics. They also felt it would be important to understand what interventions consisted of and how they worked. For example, some youth wanted to better understand how vaccines worked for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections. These young people particularly appreciated the sexual and reproductive health (SRH)- and HIV-related knowledge provided by programmes. This would also be important to allay the myths and misconceptions unfortunately still held among youth, such as beliefs that condoms could cause AIDS or that vaccines were part of a conspiracy to cause infertility and death.

It was also important for young people to feel that interventions were relevant to their needs and context. For example, many adolescents responded well to the mode of delivery and content of e-health interventions, where they felt they could relate this content to their own lives. Some young people felt that interventions were not acceptable if they clashed with the broader social, cultural, and religious norms and practices within their families and communities.

Examples included the belief that using condoms or being vaccinated was a sin, according to the doctrines of their faith, or that their ancestors could become angry with them for using “western medicine”.

Additionally, having experienced or anticipated positive effects of interventions was closely linked to acceptability. In some cases, this referred to the interventions doing what they set out to do, such as reducing sexual risk behaviour. However, at times this extended to broader perceived social effects, such as emotional support provided through programme mentors and support groups, and potential longer-term social relationships that could develop. Feeling supported through and throughout the intervention was very important to young people.

Blandine Mekpo, a midwife at a maternity ward in Bohicon in southern Benin, provides information about AIDS to pregnant women.

A further theme that came up often, for vaccines, contraceptives, and cash transfers, was the potential positive effects on young women’s autonomy in relationships and decision-making, and their consequent ability to better protect themselves.

Conversely, anticipated, or experienced negative effects were seen as an obstacle to acceptability. Some youth expressed concerns that condom promotion, vaccine programmes, and PrEP could further encourage risky sexual behaviours, such as early sexual debut and multiple partnerships. Some mentioned fear of pain and side effects, for example, related to vaccines or circumcision. Others worried about undesirable social effects such as being stigmatised after (intentionally or unintentionally) disclosing their HIV status or other confidential information.

Privacy and protection from stigma were overall very important to young people. The privacy linked to e-health interventions, HIV self-testing, and mobile clinics, for example, was appreciated by some youth. At the same time, there were concerns about a breach of privacy through e-health interventions, for example where phone sharing was necessary. One suggestion raised was to work with pre-agreed coded messages and protect the clinic’s or provider’s identity.

Adolescents and youth were more likely to find interventions acceptable if they didn’t feel that the related costs, or efforts needed to participate, were too high. For example, concerns were raised around the cost of purchasing condoms, sending SMS messages for e-health interventions, and buying HIV test kits.

Some young people also spoke about barriers to accessing certain interventions, which could exclude some youth and worsen inequality in their communities. One example given was mobile phone ownership as a prerequisite for participating in e-health interventions.

Lastly, the social dimension of acceptability emerged from our work, since many young people were influenced by their perceptions of whether other important people in their lives would accept the intervention or their participation in it. For example, for young women, family members and friends could be strong motivators for the uptake of vaccines and family planning benefits, while peer participation could encourage young men to opt for VMMC.

Students from the University of the Witwatersrand explain the HIV self-testing kit, in Hillbrow, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Some gender-related dynamics emerged from our review. For instance, a few studies suggested that young men were more likely to see vaccines or PrEP as an opportunity to stop condom use and engage in multiple sexual partnerships. One study showed that the acceptability for HIV testing at schools and VMMC was higher among females, while another showed higher acceptability of the HPV vaccine among males.

However, we should be cautious about drawing gender-based conclusions from these findings, since the available evidence is thin. Only 14 studies in our review disaggregated results by (male versus female) gender and only six highlighted gender differences in acceptability findings. None of these studies adopted a broader conceptualisation of gender or worked with minority groups of young people.

Our review work identified several factors that intervention developers and implementers should pay attention to if they want to increase the acceptability, uptake, and efficacy of programmes and services among young people in Africa.

Our findings suggest that it is important to strengthen young people’s knowledge of interventions and how to interact with them, but also to engage with the broader context that shapes their perspectives and decisions. One way to achieve this is to involve adolescents and youth – and potentially other key stakeholders – early in the design, planning, and scale-up of interventions, and at various stages of the intervention life cycle. However, our work also revealed that, unfortunately, very few studies do this and hardly any provide opportunities for meaningful youth engagement. There is a clear opportunity here to offer young people a real “seat at the table” to share ideas and solutions that will improve their lives, as argued by the Youth Transforming Africa (YTA) Network and World Bank Group.

Peer educators compete to inflate condoms during a ‘condom olympics’ presided over by self-declared ‘Africa King of Condoms’, Stanley Ngara, during a World AIDS Day commemoration in Nairobi, in December 2021.

eHealth interventions are worth a special focus in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the digital revolution in which young people are protagonists. Our findings highlight the opportunities and risks of these types of interventions, and multiple potential reasons for their low and high acceptability. Service providers and programme developers should focus on finding ways to enhance potential positive aspects of digital or hybrid interventions – such as lower access costs, privacy, and relevance to young people’s lives – while managing and minimising potential risks, such as unequal access to connectivity and devices, management of confidential information and lack of in-person interaction.

There is also clearly a need to better incorporate gender in the conceptualisation and assessment of intervention acceptability among young people. This is crucial because health access, risks, and behaviours often have a gender dimension. For researchers and practitioners, this should mean working with different gender groups, and, where possible, disaggregating findings by gender.

This should also mean paying further attention to gender norms, relations, and power asymmetries as key social factors shaping intervention acceptability. Moreover, future studies should adopt a broader definition of gender, and work with key and often marginalised minority groups of young people, such as LGBTQIA+ youth or young people living with disabilities. This is important because minority youth populations in Africa are more likely to experience stigma and other barriers when trying to access health and social services.

By better understanding what drives and hinders the acceptability of interventions among young people broadly, and specific high-risk groups within this population, researchers and practitioners will be more equipped to address their needs. This will enable them to improve the opportunities for a new generation of young men and women transitioning into adulthood.

Marisa Casale is an Extraordinary Professor at the University of the Western Cape’s School of Public Health (SOPH) and an Associate Member of Oxford University’s Department of Social Policy and Intervention. She is currently leading a work package focused on translating evidence into impact, within the UKRI GCRF Accelerating Achievement for Africa’s Adolescents Hub.