Good Governance Africa (GGA) expresses deep concern over the lack of inclusive governance in Eswatini, which casts a shadow over the credibility of the forthcoming elections on 29 September.

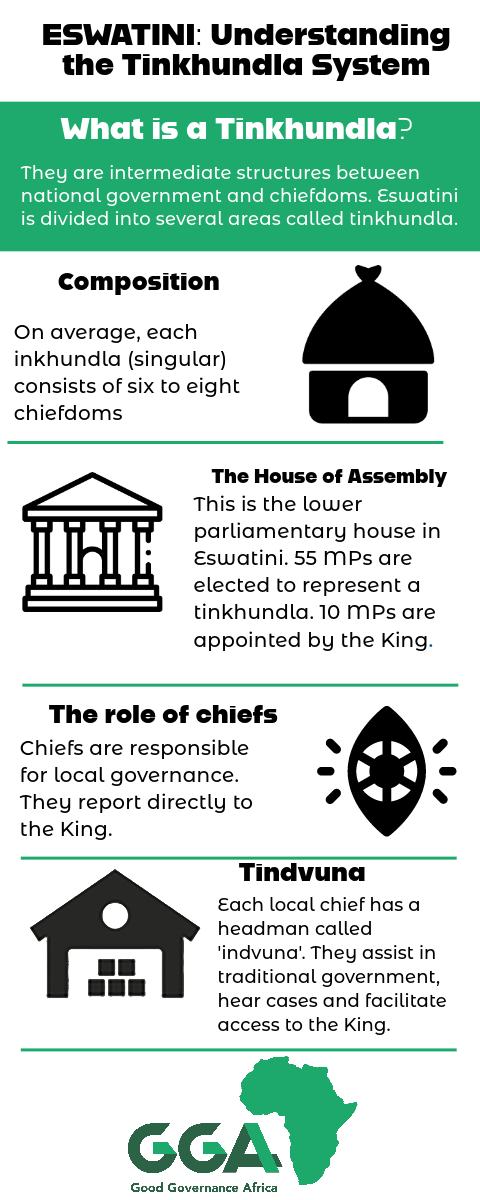

King Mswati III rules the country as an absolute monarch through a questionable ‘traditional’ tinkhundla system of governance, and political parties are banned in terms of the constitution, raising concerns about political freedom and representation.

King Mswati III arrives at the annual royal Reed Dance at the Ludzidzini Royal Palace on August 28, 2016, in Lobamba, Eswatini. Photo by MUJAHID SAFODIEN/AFP

Chris Maroleng, International Chief Executive Officer, says the structure of Eswatini’s political system would matter less if the country had high levels of economic and social development, but “instead, it brings into sharp focus that under this system of governance, the King gets to do as he pleases, and the Treasury is the King’s purse”.

The juxtaposition between King Mswati III’s estimated wealth of around $200 million and the economic challenges faced by the majority of his subjects is stark. The country had a GDP per capita of just $4,018 in 2021, an unemployment rate of 40%, and 69% of the population living below the poverty line. This is particularly galling given the ruling family’s tenuous claim to royalty.

Under the tinkhundla system, local chiefs, appointed by the King, oversee administrative regions.

The Parliament (or Libandla) is bicameral, consisting of a lower chamber (the House of Assembly) and an upper one (the Senate). Some members of both chambers are elected, while others are appointed by the king, a system Maroleng describes as a mere pretence at democracy.

“The absence of political parties and the influence of the monarchy are barriers to free and fair elections. While we respect that the country’s electoral process seeks to incorporate elements of its rich cultural heritage, GGA stands for democracy, human rights, the rule of law, accountability, and transparency. All these values need to be adopted in Eswatini, instead of the persistent, profligate rule by a king who is known for excess,” Maroleng added.

GGA has also noted with alarm the violence that has occurred in the past in Eswatini under security legislation introduced in 2022. The narrowing of democratic space continues to undermine the credibility of the elections and the system of governance in Eswatini as a whole.

Encouragingly, there appears to be a sea change among the younger population in their attitude towards the absolute rule of the king. This shift is a beacon of hope for the future of Eswatini.

In conclusion, there clearly exists a strong need to create and strengthen institutions that will assist in upholding the rule of law and that will broaden democratic practices in the “participatory-based system” that Eswatini citizens deserve.