The dried inland Lake Chilwa in Zomba District, eastern Malawi, October, 2018. Drought is one of the adverse effects of climate change. Photo: Amos Gumulira/AFP

Climate change is perhaps the epitome of a ‘wicked problem’. On the one hand, it is a relatively abstract concept, the concrete reality of which is difficult to communicate. On the other hand, its felt effects are already very real in terms of increased flood, fire and drought frequency. These negative impacts tend to land on those who can least afford it, and who had the least to do with creating the problem in the first instance. The problem is ‘wicked’ in the sense that it has multiple inter-connected causes and creates a significant collective action problem when it comes to solving it. Solutions must be multi-faceted, as there is no silver bullet.

In November, the United Kingdom will host the 26th annual United Nations (UN) global climate summit – called COPs – or ‘Conference of the Parties’ in Glasgow. COP26 (delayed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic) has a unique urgency and could prove to be one of the most important conferences of our time. Most experts agree that the window for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees is rapidly closing, and the decade out to 2030 will be the most critical to achieving this target.

In 2015, at COP21, the landmark Paris Agreement was born. Under the Paris Agreement, countries committed to developing national action plans known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which outline their individual contributions in terms of policies and measures to achieve the Agreement’s global targets. This year, countries are expected to present their updated NDCs for the next five years. However, over 70 countries are yet to submit their updated NDCs and of those who have submitted, many have presented even less ambitious targets than they did in 2015.

The latest assessment report (AR6) by the International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) indicates that unless major reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions are achieved in the next two decades, we will experience a global average temperature increase of 3 degrees or more (above pre-industrial levels) in the second half of the century. This would be catastrophic. In this scenario, Africa will be the biggest loser.

As Youba Sokona, vice-chair of the IPCC, stated on the release of AR6: “All of Africa, in general, is vulnerable, given the level of development. The entire continent is highly exposed to climate extremes, at a relatively high level of vulnerability, which amplifies the problems that the continent is experiencing, including poverty, limited infrastructure, conflicts and urbanisation in development.”

Over the coming weeks, GGA will engage a variety of experts on climate change challenges facing Africa, adaptation costs and strategies, and how to ensure a just transition to low carbon economies on the continent. More specifically, we will be looking to identify what African leaders should be prioritising ahead of COP26, what commitments we would like to see from the international community, and the role that public and private sector stakeholders can play in supporting these initiatives.

COP26: What’s at the top of the agenda?

- Securing global net-zero by 2050

States are being asked to set ambitious 2030 emissions reduction targets to secure net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 to keep the global target of 1.5 degrees warming (above pre-industrial levels) within reach. To deliver on these targets, the UN is calling on countries to:

- Accelerate the phase-out of coal

- Curtail deforestation

- Speed up the switch to electric vehicles

- Encourage investment in renewables

- Adaptation

The latest report by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) outlines widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere due to global temperature increases. These changes, in turn, will amplify average temperature increases, shifts in seasons, and generate a higher frequency of extreme weather events regardless of whether we reach the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Accordingly, COP26 has mainstreamed the importance of supporting countries and communities to develop adaptation solutions that are contextually practicable to their ecological, social, and economic systems to respond to the already-occurring impacts of climate change, as well as prepare for future impacts. These measures can include everything from the building of flood defences, setting up early warning systems for cyclones and switching to drought-resistant crops.

- Mobilising financing

In 2009, at COP15, developed nations agreed to raise $100bn in climate finance per annum by 2020 to support developing nations cope with the rising impacts of climate change and move to lower carbon economies. The OECD’s third assessment of progress towards the goal found that climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries for developing countries totalled $78.9Bn in 2018 – the highest amount since 2009. The COVID-19 pandemic and global financial recession would likely have seen this amount drop substantially over the past two years and will be a central focus of discussions at COP26. Sufficient climate finance is critical to effecting a truly just transition to renewables and a net-zero growth path.

- Delivering on promises

In 2018, parties adopted detailed rules and procedures for implementing the agreement, known informally as the Paris “rulebook”. This rulebook puts the guidelines of the Paris Agreement into place and tells countries how they should work together to achieve a low-carbon and climate-resilient future. This includes guidance on developing NDCs as well as reporting standards for countries that provide financial, technological, and capacity building-support for other countries. While the Rulebook was adopted in 2018, there are still several parts outstanding which will be the focus of discussions.

What should be Africa’s priorities at COP26?

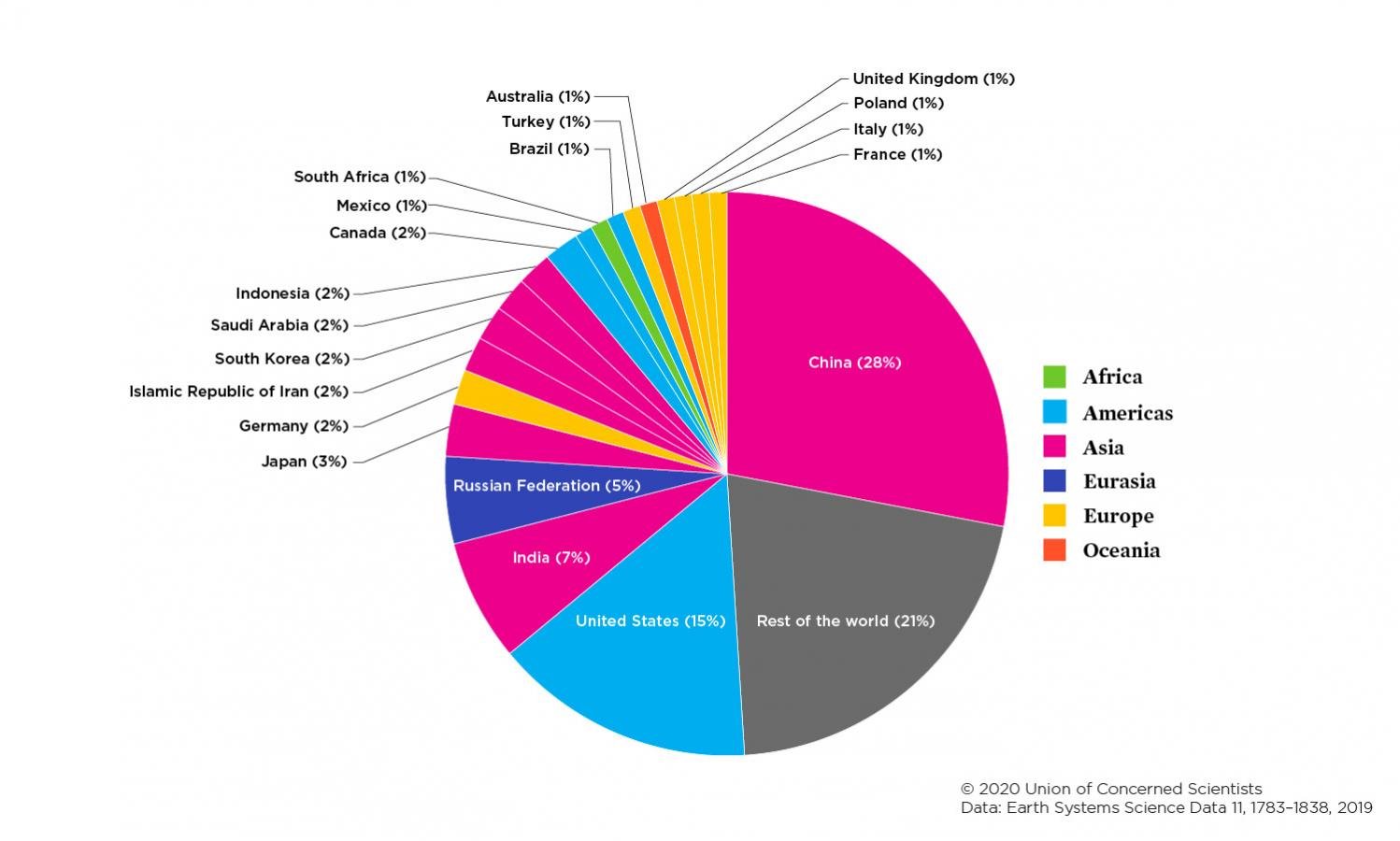

Africa deserves extraordinary attention at COP26: while the continent contributes just 4 percent of global total greenhouse gas emission, its socio-economic development is threatened more than any other region by climate change. Preventing further vulnerability alongside taking responsibility for mitigation and adaptation initiatives will require concisely articulating the continent’s needs on core issues and smart negotiations by our leaders. These include, among others, the following:

- It is crucial that developed nations do not shift their climate responsibilities, particularly regarding their cumulative GHG emissions, to developing nations, and must lead with clear targets for reaching net-zero by 2050. As indicated in the chart below, developing countries (aside from China) account for a small proportion of GHGs.

- According to the UN’s Environment Programme(UNEP), the annual adaptation costs in developing countries, currently estimated at $70 billion, will rise to $300 billion by 2030 and $500 billion by 2050. Developed nations must not only make good on their commitment of $100bn in financial support per annum, but this figure should be seen as the floor and not the ceiling in climate development funding to ensure that net-zero ambitions are not jeopardised.

- Africa also needs additional support for the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI), anAfrican-led initiative to generate at least 300 gigawatts of power from renewable energy by 2030, and the African Adaptation Initiative (AAI), aimed at strengthening adaptation action across the continent.

The COVID-19 pandemic and rising debt have weakened developing nations’ capacity to tackle the climate crisis despite shouldering most of the burden of its impact. Developed nations have a moral responsibility to play a greater role in assisting African states to adapt to climate change and to transition to low carbon economies. Simultaneously, this presents an opportunity for the continent to forge a new growth trajectory based on inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Stephen Buchanan-Clarke is a security analyst with several years' experience working in both conflict and post-conflict settings in Africa, primarily on issues of peace and security; transitional justice and reconciliation; democratisation and governance; and preventing and countering violent extremism. He currently serves as head of the Human Security and Climate Change (HSCC) project at Good Governance Africa and is a co-editor of the Extremisms in Africa anthology series.