Last month, Minister of Electricity Kgosientsho Ramokgopa proposed to delay the decommissioning of Eskom’s coal-fired power stations. This comes amid ongoing challenges to end South Africa’s energy crisis and rolling blackouts (load-shedding). The country is now on what appears to be semi-permanent “stage 6” load-shedding, which means that less than half the country’s installed capacity is available at any given time. Without power, the economy has ground to a halt, and even the delivery of basic public services such as clean water has been jeopardised.

If Ramokgopa’s proposal is executed, it will stand in direct contrast to commitments made in the Energy Crisis Action Plan and the R8.5 billion climate-finance deal agreed to last year toward a Just Energy Transition and threatens an already critical health crisis in the Highveld Priority Area (HPA).

The towers of the coal-fired Rooiwal Power Station are seen on the outskirts of Pretoria, on October 13, 2021. Photo by Michele Spatari/AFP

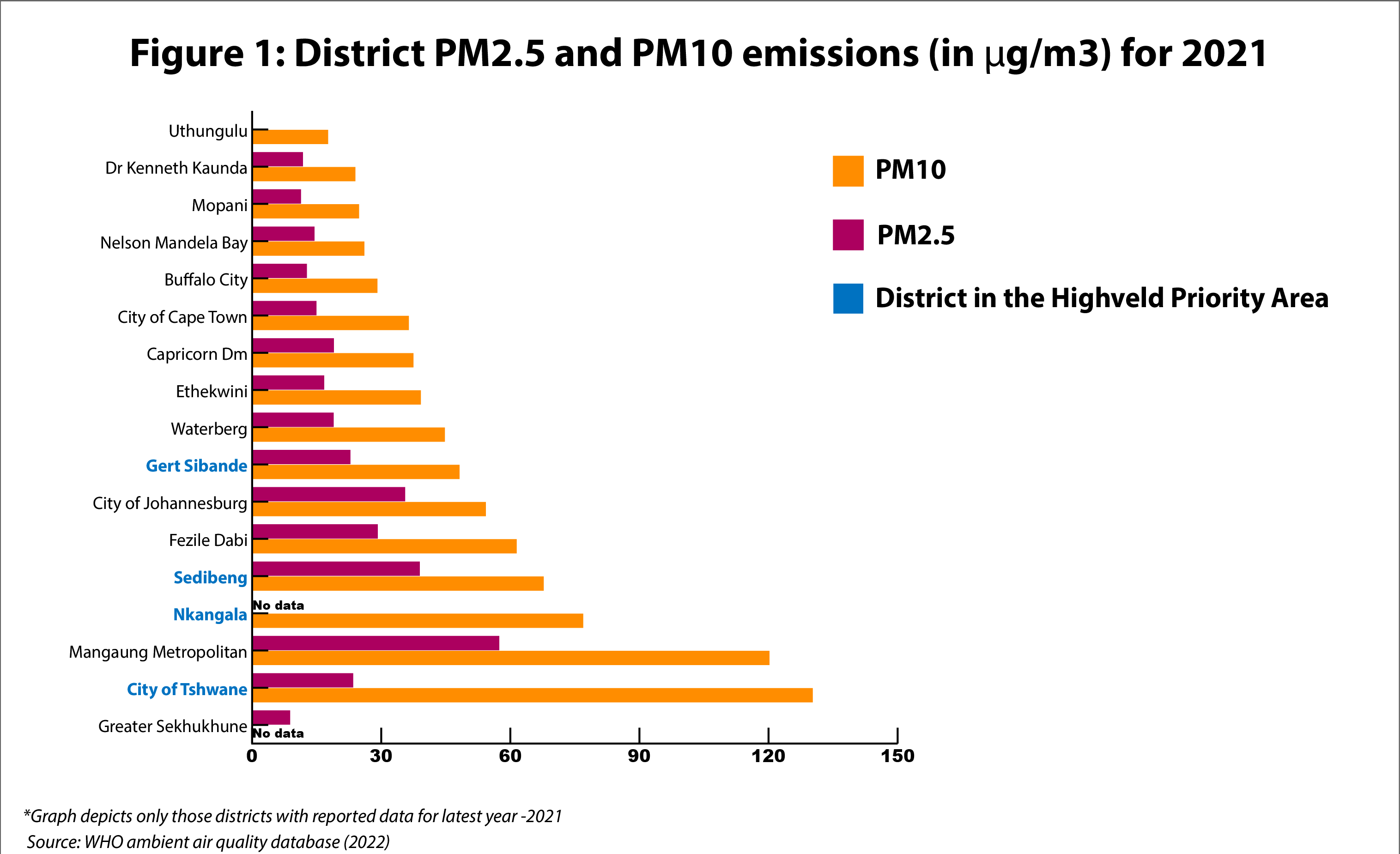

Annually, air pollution caused by South Africa’s coal operations results in the deaths of thousands and compromises the health and livelihood of people living in the Mpumalanga highveld and densely populated regions of Ekurhuleni, Tshwane and Johannesburg. Those living in the Waterberg district in Limpopo and the Free State are also negatively affected (Figure 1).

According to an independent expert study conducted by Dr Mike Holland in 2017, the impact of air pollution from Eskom’s coal power stations alone includes over 94,000 cases of asthma symptom days in children, more than 9,500 cases of bronchitis in children, nearly 2,800 cases of chronic bronchitis in adults, 2,400 hospital admissions, and a loss of one million working days each year.

According to reports from the Centre for Environmental Rights (CER), air pollution from coal-fired power stations results in thousands of cases of bronchitis and asthma in adults and children, the estimated costs of which are over R30 billion annually, through hospital admissions and lost working days.

On speaking with CER representatives about the developments in the country’s energy crisis action plan and the ANC’s recent proposal they said:

It is disappointing to observe that the impact of air pollution on communities and the fact that there is a public health disaster in Mpumalanga, is not being appreciated and considered in crucial decision-making and the rights infringements of residents are being perpetuated. The plan promotes the untenable narrative of a trade-off between lives and electricity. The CER and other organisations have been working on air-pollution-related health issues in the Priority Areas and have been presenting modelling on the health impacts of air pollution from industries like Eskom, as well as the effect of this on the fiscus to both the government and industries for decades. – Ntombi Maphosa, Attorney at the CER Pollution and Climate Change.

Despite recognising the socio-economic consequences associated with the closure of coal plants, insufficient efforts to expedite the implementation of renewable energy only delay and even threaten to exacerbate these concerns. It has been projected that, at current PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, there will be more than attributable to air pollution between now and 2050. If all the country’s coal mines were shut down tomorrow, 90 000 people would go without immediate income, which is one of the government’s key concerns. However, almost 10 times that number of people could avoid unnecessary early death in the scenario where coal-fired power was phased out.

Outgoing executive director of the CER and member of the Presidential Climate Commission, Melissa Fourie has noted: “These numbers should make us lie awake at night. Air pollution from coal and other fossil fuels is an acute public health crisis in SA. We are knowingly causing harm to the lives, health and development prospects of hundreds of thousands of people, including children — some even before they are born.

- “As a country, we owe a debt of restorative justice to the people who have suffered and continue to suffer the health consequences of our reliance on coal and other fossil fuels. This should be a major consideration in the design and prioritisation of interventions in the just.”

The proposal also follows the state’s leave to appeal the Deadly Air court judgement about air pollution in the Mpumalanga Highveld granted by the Pretoria High Court last month. The landmark judgement (by) was first passed in March 2022 in which the Pretoria High Court declared the air quality in the HPA a violation of residents’ constitutional rights to a safe environment that does not pose a threat to their health and well-being. The judgement ordered the state to enforce the Highveld Priority Area Air Quality Management Plan to meet air quality standards in the Mpumalanga Highveld region.

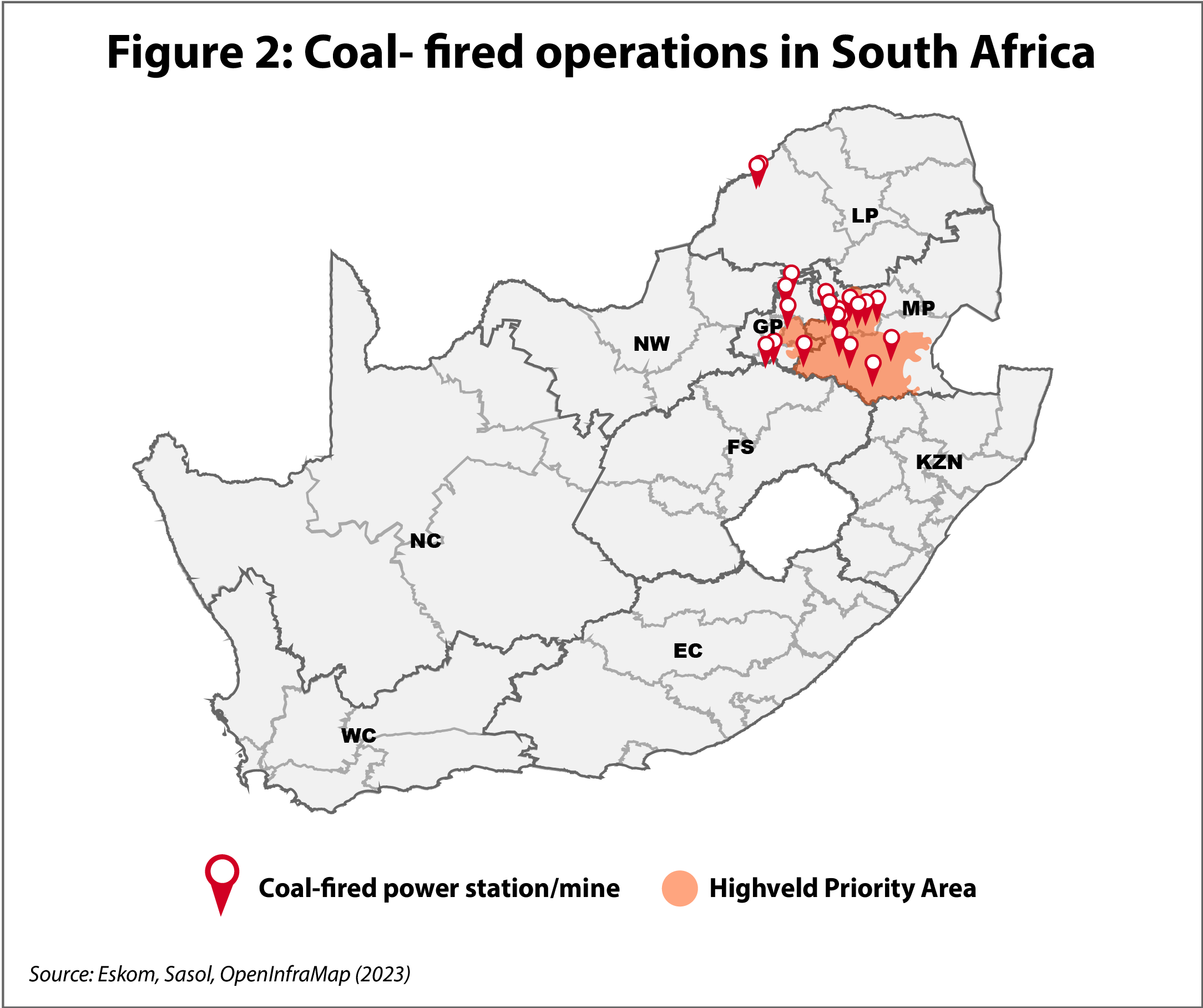

Currently, the state utility operates 15 coal-fired power stations, 12 based in Mpumalanga. Moreover, energy company Sasol Ltd operates 5 coal mines (Bosjesspruit, Impumelelo, Shondoni, Syferfontein and Thubelisha collieries and Twistdraai export operations) at their Sasol Secunda complex in Mpumalanga and is reported to be one of the top polluters in SA, after Eskom (Figure 2). Additionally, 33 coal-mining operations are reported to be active in the same region according to the Minerals Council South Africa.

According to the CER, new data published by Urgewald and Reclaim Finance showing investment flows into oil, gas and coal companies revealed that the top three investors in companies in South Africa have combined share and bond holdings of USD 13.5 billion in fossil fuels companies.

The top institutional investor in SA was reported to be the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) with roughly USD 7.4 billion invested in coal, oil and gas companies. The GEPF was followed by asset management company the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) with a reported USD 3.4 billion invested in fossil fuel companies. The report revealed that in third position is Anglo-South African asset management business Ninety-One, investing over USD 2.7 billion.

Ranking in fourth was Coronation Fund Managers with an estimated USD 782 million and in fifth position was international banking and wealth management group Investec reportedly investing over USD 629 million into oil and gas projects in the country. In comparison, the USD 8.5-billion the country managed to secure from international partners following the COP26, in Glasgow to fund its decarbonisation plan represents only half of the USD 15 billion generated from just five investors.

The report also reveals that top companies investing in fossil fuel companies unsurprisingly include Sasol (with a total invested of USD 8 810 million) and Eskom (at USD 8 008 million) ranked first and second respectively. They are followed by Exxaro Resources (USD 2 327 million), Transnet (USD 1 192.4 million), Thungela Resources (USD 894.6 million) and Grindrod (USD 169.5 million).

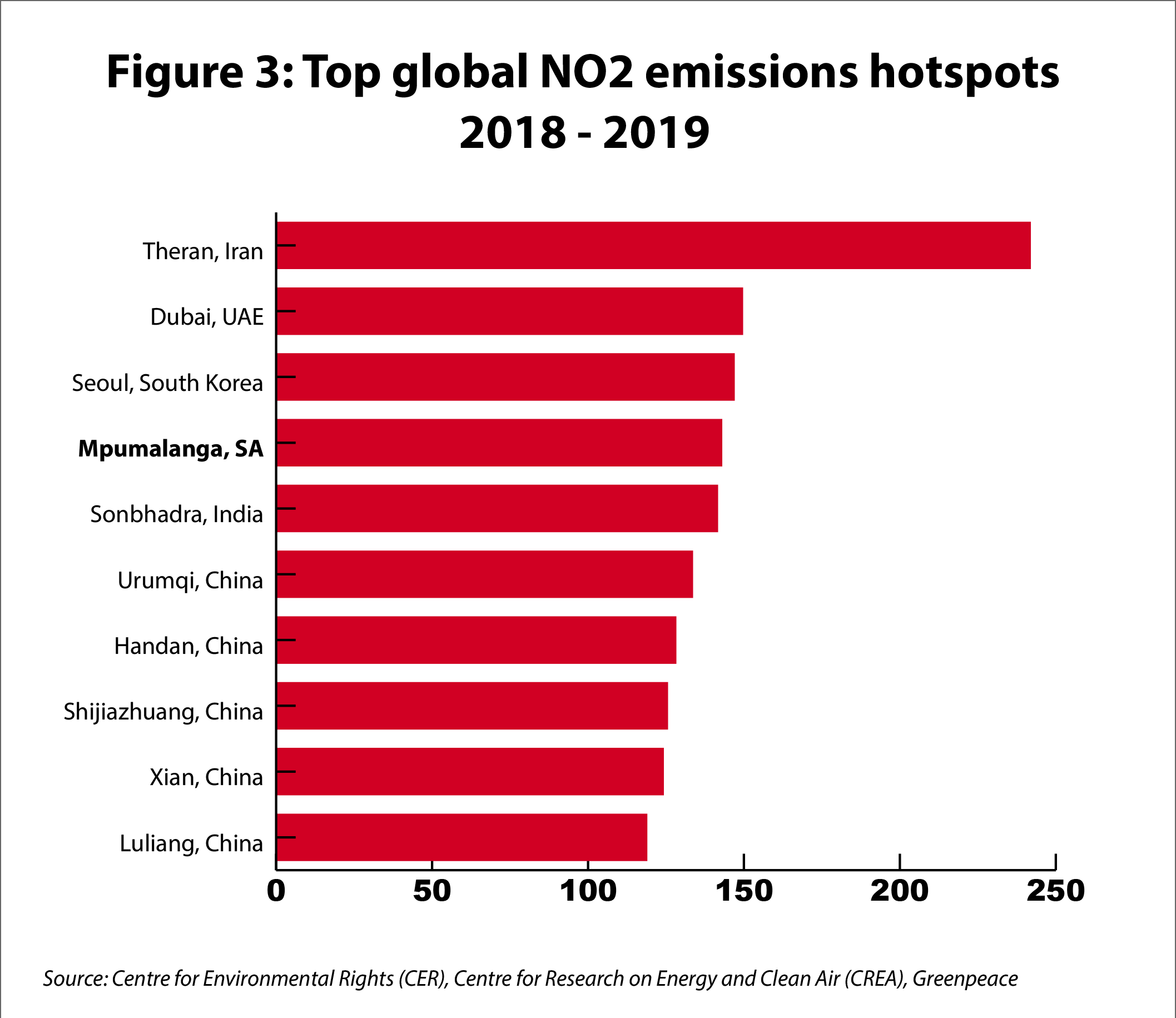

Eskom’s coal-fired power stations remain the primary culprits of the health crisis in these regions with their operations resulting in high levels of particulate matter, sulphur dioxide, and nitrous oxides (Figure 3) that often surpass health-based ambient air quality standards.

On the matter, the Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment’s (DFFE) application for a leave of appeal, based on a narrow legal issue relating to the interpretation of section 20 of the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act (AQA), acknowledges the responsibility of his department to manage the crisis but reveals its enthusiasm to alleviate the health problems arising from air pollution to be underwhelming and inadequate.

Meanwhile, Sasol Limited’s – whose Secunda facility is known to be one of the biggest GHG emissions globally – decarbonisation strategy and 2050 net zero ambitions remain too vague and fail to take any real climate action. The company has also brought forward several applications to postpone the implementation of minimum emission standards (MES) and avoid accountability for MES compliance.

When reached out to for comments, neither Sasol nor Eskom responded.

The health implications of air pollution are severe and wide-ranging and are in breach of residents’ section 24(a) Constitutional right to an environment that is not harmful to their health and well-being. Minister Ramakgopa’s proposal poses a direct challenge to the commitments made toward the Just Energy Transition ambitions and continues to exacerbate an already critical health crisis.

Unless the state commits to decarbonisation efforts, the country’s health and economic potential will continue to be compromised. Policymakers need to stop creating false dichotomies between pollution and livelihoods. Mining and burning coal are devastating the health of the nation, while livelihoods derived from these activities are invariably compromised by direct health impairments. Therefore it behoves the state to make different energy choices.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.