Why Africans still vote for toxic post-liberation tyrants

Since the end of colonialism, apartheid and white-minority regimes, many African countries appear to have had disproportionally large numbers of psychopathic, narcissistic and just mean-spirited leaders.

All these types of leaders in many cases focus on their own self-aggrandisement, often deliberately sowing societal or ethnic divisions for self-enrichment and looting public resources. In power, they also deliberately cause chaos, confusion and uncertainty – to perpetuate their rule.

African countries, with their high levels of poverty, contestation over legal, cultural and moral codes, and lack of direction, are fertile ground for psychopathic, narcissistic and mean-spirited leaders.

Ravi Chandra, one of the leading psychologists of political leadership, says such leaders are “not beholden to laws or responsible to their relationships, organisation, community or even country as a whole”.

Many African liberation movements, in the fight for independence, pursued armed struggles, engaging in guerrilla warfare or violent protests. Examples include South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC), Zimbabwe’s Zimbabwean African National Union- Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF), Algeria’s National Liberation Front (NLF), Angola’s People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo).

A second group of liberation movements are those that did not fight colonial, apartheid or white minority regimes, but fought brutal first generation, post-colonial dictatorship. Examples of these include the National Resistance Army, under the leadership of Yoweri Museveni, who fought Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, one of the particularly brutal first generation African post-colonial dictators.

Another example is Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriot Front, which fought the dictatorial government of Juvénal Habyarimana. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of rebel groups that fought and overthrew the brutal Derg dictatorship under Chairman Mengistu Haile Mariam, also fought an indigenous post-colonial dictatorship.

In violent military struggles, as was the case in the struggles for liberation or independence in Africa, hard leaders, often psychopathic narcissists, who talk tough rhetoric against the oppressors, rise easily through the leadership ranks.

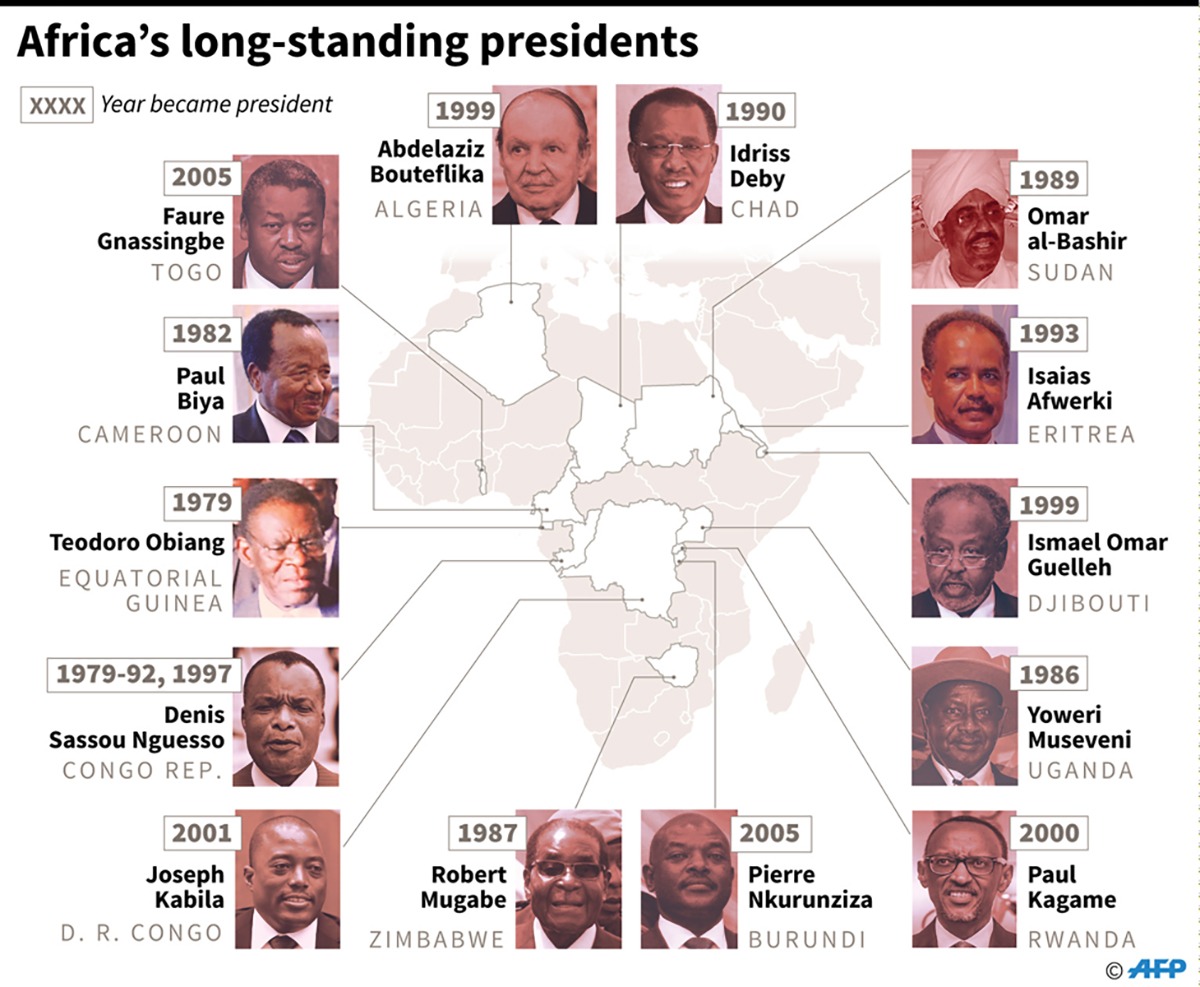

Cases in point are former Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe and Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni. Mugabe, to stop the Zimbabwean Congress of Trade Unions from embarking on a strike in 1998, warned them: “I have degrees in violence”.

Colonialism, apartheid and dictatorship caused mass trauma to the individuals who experienced them. Carolyn Hilarski, a trauma specialist from the State University of New York, defines historical trauma as: “experienced by a specific cultural, racial, or ethnic group. It is related to major events such as slavery, the Holocaust, forced migration, and violent colonisation”.

Research has shown that mass trauma, such as colonialism, apartheid and dictatorships, and chronic long-standing poverty and unemployment, can alter the way the victims make decisions, the leaders and parties they support and how they vote.

Research has shown that mass trauma, such as colonialism, apartheid and dictatorships, and chronic long-standing poverty and unemployment, can alter the way the victims make decisions, the leaders and parties they support and how they vote.

Moreover, Miri Scharf and Ofra Mayseless from Israel’s Haifa University, in a study first published in 2010, revealed that unprocessed trauma, which caused problems in communication and interaction, could even be transmitted from victims of historical and communal trauma, across second and third generations. The second and third-generation offspring of victims of trauma, although they did not experience the trauma themselves, often also behaved as if they had done so directly.

The study focused on second-generation Israelis who were descendants of Holocaust victims and their children. The study was done on healthy adults, with no apparent psychological problems.

Similar conclusions can be reached about the descendants of African victims of trauma from colonialism, apartheid and dictatorships. One of the consequences of trauma is that in many African countries, the poor, marginalised and desperate regularly support leaders and parties that, on the face of it, go against their own interests, only further increasing their poverty, marginalisation and underdevelopment.

This is one of the reasons why Africa has remained overwhelmingly poor since the end of colonialism. Power-hungry, violent and cruel leaders, with their populist rhetoric, corrupt behaviour and ill-suited policies, crash economies, which lead to mass starvation, societal breakdown and violence.

In Zimbabwe, for example, the poor consistently voted for the late Robert Mugabe, even as his policies caused immense suffering. In South Africa, many desperately poor communities have supported former president Jacob Zuma as leader of the country and as party leader, thereby voting to continue their own poverty, marginalisation and underdevelopment. In Uganda, people have continued to support Yoweri Museveni, who has clung to power for 35 years, leading the country into continuing cycles of decline, decay and disorder.

Sadly, many ordinary Africans are often so traumatised by the legacy of colonialism or first-generation post-colonial leaders that they believe the likes of Museveni, Mugabe and Zuma single-handedly liberated them from former oppressors.

Lieutenant Colonel Haile Mariam Mengistu, Ethiopian president, taken during an official visit to Cuba, 25 April ,1978. Photo: Prensa Latina/AFP

Although independence and liberation were achieved decades ago, these leaders often still blame colonialism, apartheid and imperialism for present governance failures, usually a cover-up for their own incompetence and corruption. Voters lap this up – and continue to support them, despite their failures.

These leaders and their parties often castigate black opposition parties as surrogates of former colonial powers and former apartheid governments who, if elected, will bring back these former colonial powers and apartheid governments.

“Puppets of the British will never rule Zimbabwe”, Mugabe said in 2003 of Morgan Tsvangirai, the leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which was challenging the ruling Zanu-PF government.

Mass trauma has instilled a deep fear, anger and resentment among many black communities for former colonial and apartheid elites. The problem is that fear, resentment and anger-based politics against the former colonial powers and the apartheid government creates the environment that makes political leaders who seemingly in rhetoric provide a “fight-back” against the objects of the fear, resentment and anger, more appealing.

So, mass traumatised, formerly oppressed communities appear to put greater value in parties and their leaders who in rhetoric, violently attack the object of their historical fear, resentment and anger, rather than those with honesty, competence and moral values.

As political parties, many of these movements give patronage only to those individuals, communities and regions that support them; and punish those that vote against them. People are so terrified of being shut out they are intimidated into voting.

The irony is that the impact of the trauma of colonialism, apartheid and dictatorships has brought to power many African leaders who mimic the oppressive behaviour of their former oppressors or dictators against their own supporters.

People queue to vote for South Africa’s national and provincial elections at a polling station in the Tlhabologang township in Coligny on 8 May, 2019. South Africans were voting in the country’s sixth democratic general election since the end of apartheid in 1994. Photo: Luca Sola/AFP

Relatedly, many former oppressed African people tolerate exploitative, corrupt and violent black leaders because they may be useless, but at least they are black – supposedly “one of us”, and not from the former oppressor communities.

Peoples’ continued support for these toxic former African liberation movements – and the support of other leaders on the continent – explains why most African countries have continued to get poorer than they were under colonialism, why these societies continue to decay and why the best local talent leaves for industrial countries.

William Gumede is an associate professor at the School of Governance, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. His latest book is South Africa in BRICS: Salvation or Ruination (Tafelberg).

I am wondering if one aspect of thing, which is to accept a system that may be oppressive and against the peoplenown interest in the hope that maybe some day, your own family, tribe, consituency will be in charge and will then be able to make it rich by plundering resources. What is missing is a strong stance and acts to fight corruption and ensure resources do go to fund health and education in priority.

Ethiopia is not under colonial era ever before. Yet you put ” …an indigineous post-colonial dictatorship…” What are you trying to say Sir?

Derg is not a post colonial regime. It came to power after the great revolution that overthrew the feudal regime of king Haile Selassie (Ras Teferi/Jah Rastafari?) Ethiopia was defeated by Italy but its hard to perceive the situation as colonization.

Nice picece. I will like to read more and also make probable solution.

For instance, in a patriarchial African society, is it continuously possible, and as a matter of deliberate policy to vote women into power for the next 20 – 30 years? Men rulers have failed woefully in fact compounded and are still compounding our woes on daily basis. African is worse than what it was some 50-60years ago. So, I submit that women should be given right of place in Africa political system as a policy.

Ethiopia is never colonized so the derg government couldn’t be considered post-colonial dictatorship. And your theory doesn’t hold there since there was no colonialism. Secondly your theory is based on the assumption most African countries vote Democratically which is laughable. If you accept the premise that the leaders are dicatators why would you assume the election Democratic?

Interesting read!!! This is the first time i have actually come across a psychological explaination as to why most incumbent post liberation leaders stay in power for such a long time. However, what i failed to get from the article is whether or not we can dismiss election rigging altogether in accounting for these tyrants stay in power. I argue that by and large tyrants are in power due to election rigging. Psychological factors yes but i dont think they have such a huge impact (my thinking).