Africa is home to an abundance of animal and plant species that attract criminal wildlife exploitation. Wildlife crime is one of the most lucrative illegal industries and it attracts – and is run – by sophisticated, transnational, well-organised criminal networks seeking to exploit the high rewards and low risks of the trade. Where fauna crimes are prevalent, there are likely to be prominent flora crime markets and vice versa. Consequently, many countries in Africa are plagued by the illegal trafficking of endangered wildlife species, and the illegal logging of timber and rare plants.

These criminal markets significantly impact almost all regions in Africa, where they have endangered entire ecosystems, dispossessed communities of their natural capital and livelihoods, reinforced poverty, and threatened national security by exploiting regional conflict, and fuelling instability.

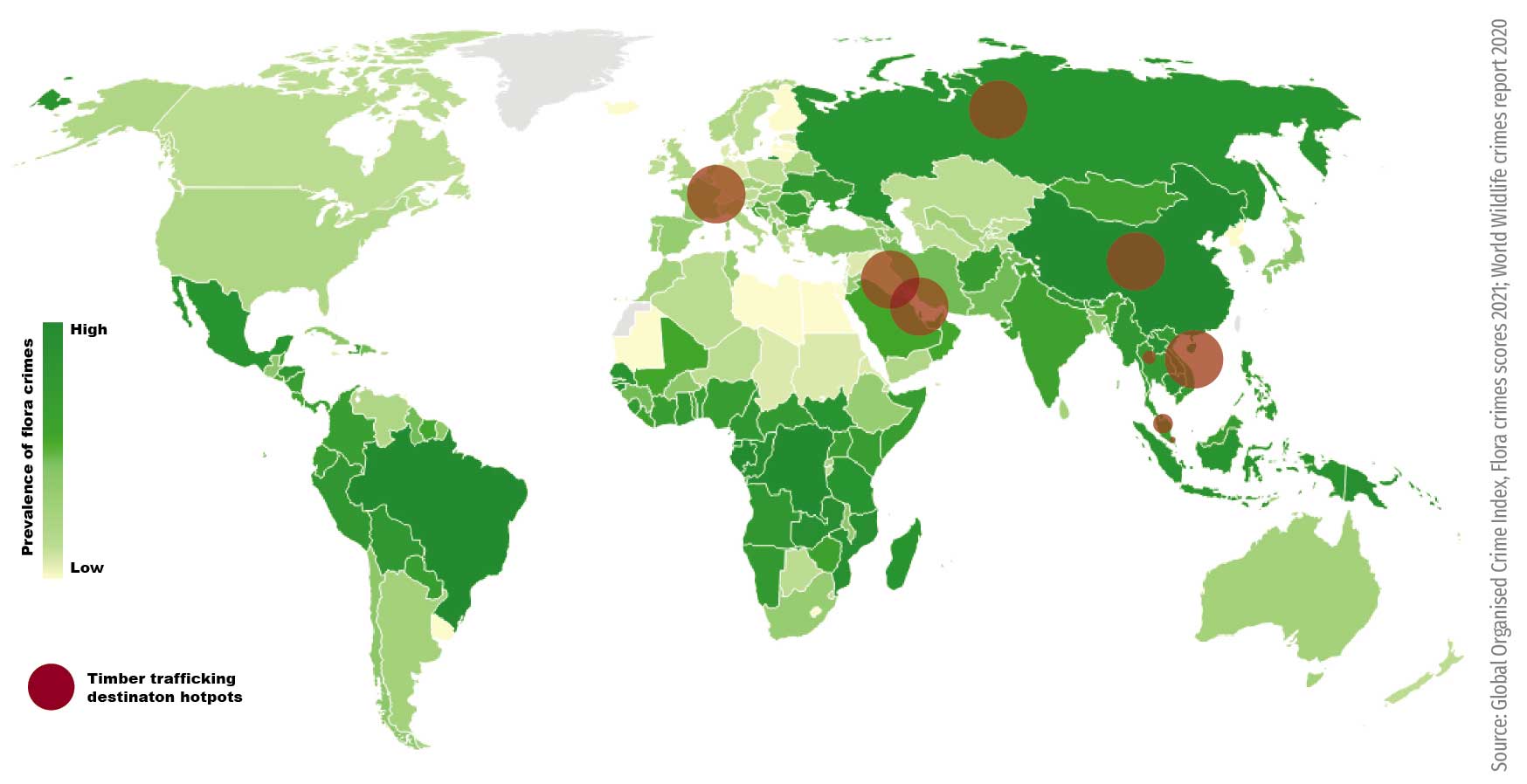

Figure 1: Prevalence of flora crimes and destination hotspots in the world. Source: Global Organised Crime Index, Flora crimes scores 2021; World Wildlife crimes report 2020

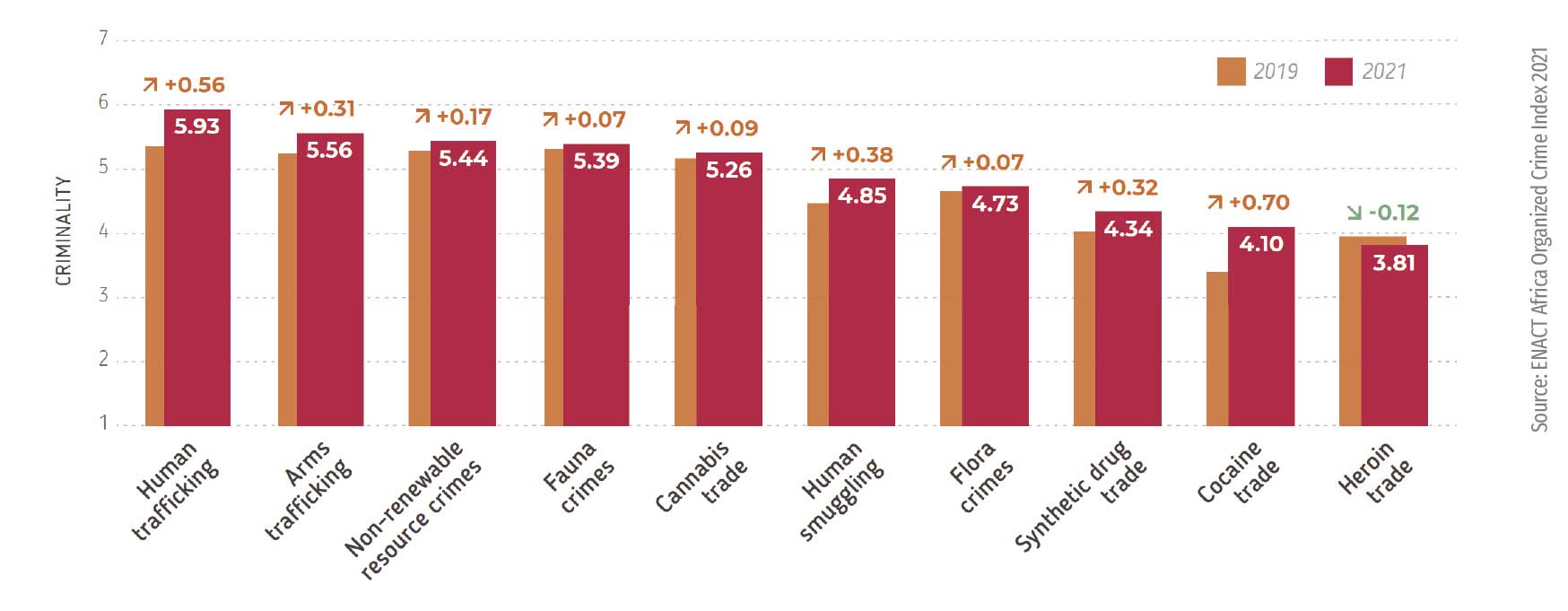

According to the ENACT Africa Organised Crime Index 2021, more than two-thirds of countries in central Africa and one-third of countries in southern and eastern Africa are severely impacted by the influence of illicit wildlife activity. Between 2019 and 2021, both flora and fauna crimes increased by +0.07 points, placing flora crimes (with an overall score of 4.73 out of 10) above the synthetic drug, cocaine and heroin trades. Fauna crimes (with an overall score of 5.39 out of 10) were below only human and arms trafficking, and non-renewable resource crimes (Figure 2).

And while the conservation of endangered animal species has received increased global attention in the past decade, illicit plant activity – particularly the illegal harvest and export of tree species – remains an under-reported and critical element of transnational organised crime. Across Africa, the exploitation of tropical hardwoods such as Kenyan baobabs and sandalwood, for their medicinal, nutritional and cosmetic purposes, forms part of a multi-billion-dollar illicit industry.

Criminal markets, African continental averages 2019-2021. Source: ENACT Africa Organized Crime Index 2021

In a report published by ENACT in January last year, researcher Willis Okumu noted that the multi-million-dollar illegal sandalwood trade had “resulted in the devastation of community forests and has placed the sandalwood tree at risk of extinction. Meanwhile, middle- and upper-tier actors in this criminal network continue to enrich themselves.”

He added that much of the confusion caused by a lack of clarity about enforcement jurisdiction had emboldened sandalwood traffickers. Okumu said that the “lack of harmony in East African conservation laws has further facilitated the protection of Kenyan sandalwood smuggled into Uganda and Tanzania”.

Also in East Africa, biopiracy and the illegal harvest of mature Kenyan baobabs, which can live up to 2,500 years, means these trees are uprooted and exported for commercial use.

A report published in The Guardian in October last year described how in Kilifi, Kenya, a group of foreign and local contractors, led by a Georgian national, Georgy Gvasaliya, had offered local residents $896-$2,700 for their baobabs, some up to 200 years old, depending on the specifications of the trees. The report said local farmers, for whom these amounts were a lot of money, had sold at least eight of their ancient baobabs to prospectors.

In the report Gvasaliya defended his activities, saying he had heard that residents were cutting down baobabs to make way for farming. “I don’t see anything wrong if we save the tree, which they can’t use for firewood or charcoal,” Gvasaliya was quoted saying by The Guardian. “I don’t see any tragedy here. The tragedy is killing trees for nothing.”

Meanwhile, in central Africa, endangered redwood trees continue to be exploited for the timber trade in the Congo Basin, and in North Africa, several countries have experienced considerable increases in the illegal logging of cedarwood and fir. But by far the most traded illegal timber in the world today is rosewood.

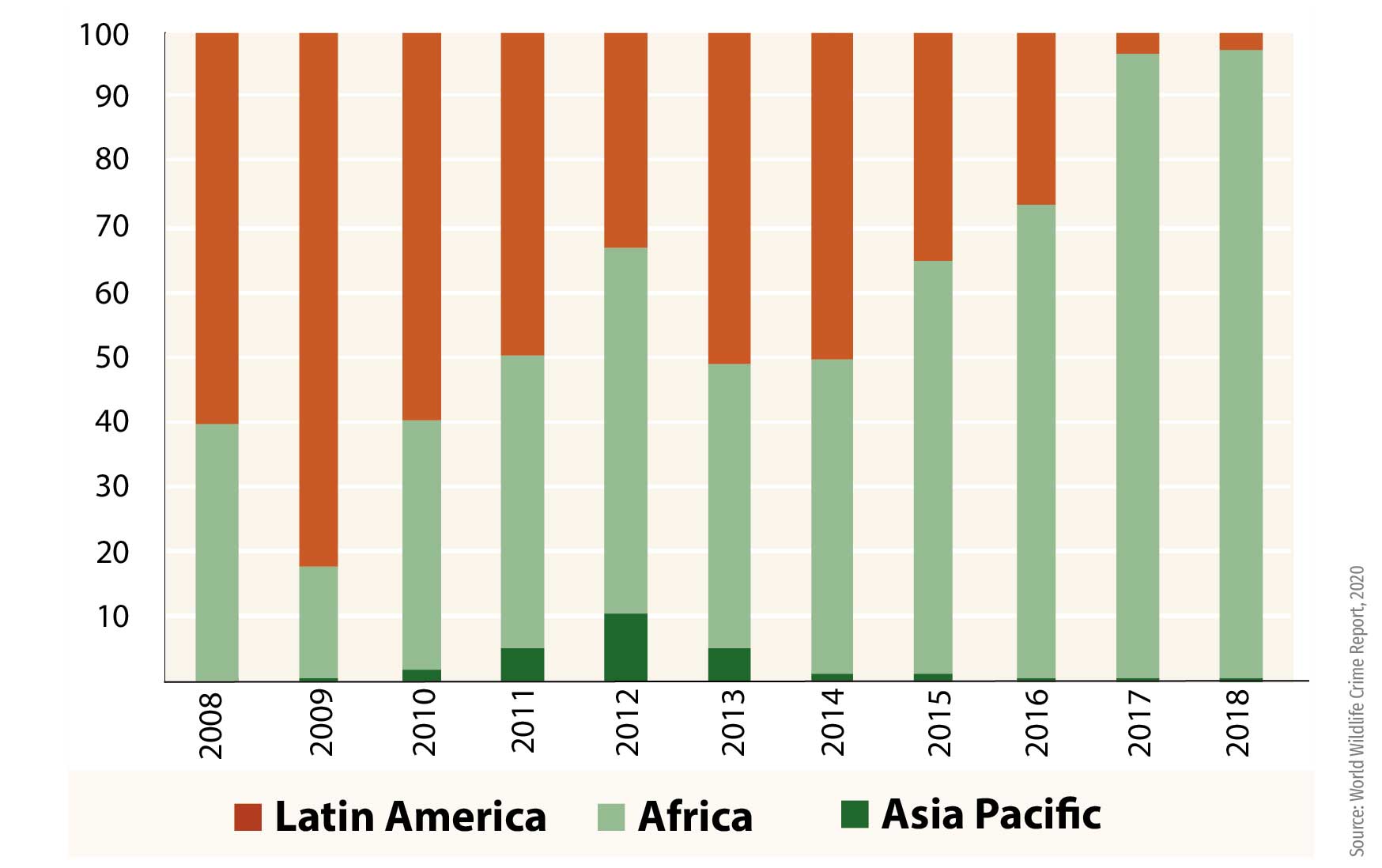

Rosewood refers to several species of tropical hardwoods often used in traditional Asian-style furniture known as hongmu, for musical instruments and for its medicinal properties. In West Africa, volumes of a particular species of rosewood, Pterocarpus erinaceus, or kosso, are often exported in violation of national laws and regulations. Elsewhere, African rosewood, Pterocarpus tinctorius, or mukula, which is found in countries such as Madagascar, Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia, is used as an imitation of kosso rosewood, due to its resemblance, and fuels a $26 billion market for Asian consumers in China (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Volume of rosewood logs to China. Source: World Wildlife Crime Report, 2020

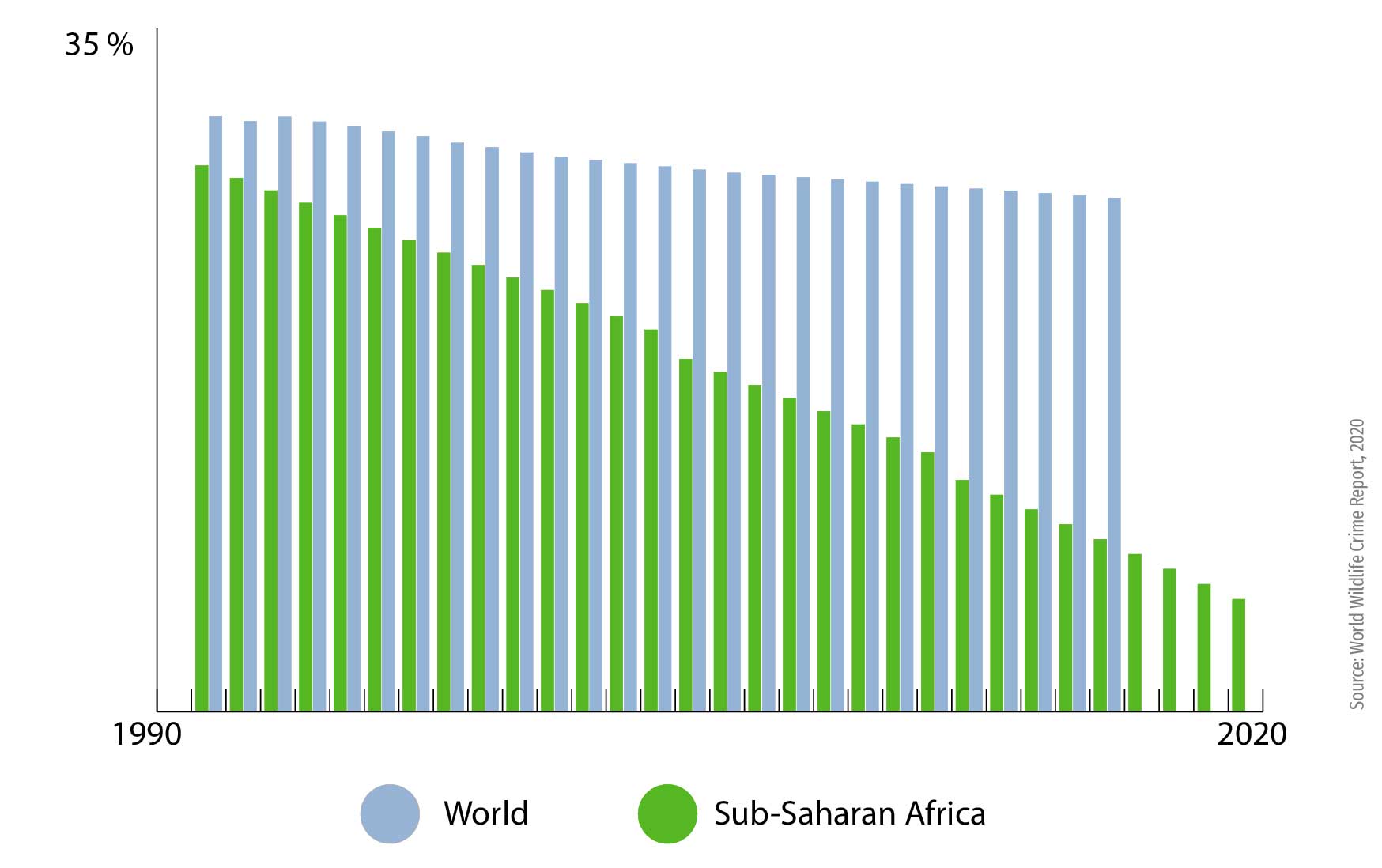

The impacts of Africa’s illicit timber trade have far-reaching socioeconomic and environmental consequences. Since 1990 Africa’s forests have experienced a loss of almost 5% of their total forest area (Figure 4). In addition to the detrimental loss of biodiversity and the degradation of critical ecosystems, illegal logging directly contributes to forest degradation, leaving them vulnerable to fires and desertification, which also exacerbates the effects of, and resilience to, climate change. A report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies notes that if the rainforests in central Africa continue to be exploited at these rates they could release the equivalent of 20 years of US fossil fuel emissions, which otherwise would have been absorbed by the only major rainforest that absorbs more carbon than it emits.

Additionally, the illicit timber trade deprives locals of their natural-resource wealth and threatens the livelihoods of communities dependent on the trees for income and medicine.

Figure 4: Decline in forest area in sub-Saharan Africa. Source: World Wildlife Crime Report, 2020

Most nefariously, illicit logging exploits regional conflicts and further entrenches instability. These sophisticated criminal networks often operate in countries already constrained by conflict or instability. A lack of security and regulation, coupled with a higher likelihood of poverty in communities makes it easier for foreign-private and local-state actors to collaborate and circumvent national laws and legislation. A recent investigation by the French NPO All Eyes on Wagner, in collaboration with European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), found evidence that the Russian paramilitary Wagner group is engaged in the forestry and timber industry in the Central African Republic (CAR).

The investigation highlighted reports in February 2021 that CAR’s armed forces (FACA) were operating in Lobaye, supported by the Wagner group, under the pretence of removing armed rebel groups from the region. However, as the investigation reveals, the EIC obtained photographs from Twitter in November 2021 of Caucasian men alongside Russian equipment felling trees that would later be traced to a company called Bois Rouge’s website. Elsewhere, hardwood trafficking networks in east and central Africa have been linked to extremist groups such as the Ahlu-Sunnah Wa-Jama in Tanzania.

Stumps of hardwood Mopani trees, in the Mhondoro Ngezi district, Zimbabwe, felled by fire because their diameter made them too large to easily cut down. Zimbabwe is losing more than 330,000 hectares of forest annually. Agriculture is still the number one driver of deforestation. Photo: Jekesai Njikizana/AFP

Illegal logging engenders and exploits a vicious cycle of opaque governance and instability in the regions in which criminal networks are found and operate. Disrupting these criminal operations requires greater transparency, coordination and accountability from affected governments (both source and destination countries). African governments are estimated to lose $17 billion annually to the illicit timber trade. As such, greater regulation of trade activity within country borders, according to national legislation and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) international legal order, is essential to confront this threat.

According to a report by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime at present the barriers to confronting the illicit timber markets in Africa are:

- The response to environmental crime is inadequate

Despite a shift in global narratives regarding the severity of environmental crimes, responses have been slow and inadequate. Environmental crimes remain an underestimated threat and an underrated global priority. And as result, many criminal actors continue to operate unscathed. Additionally, seizures of timber products and arrests remain an inadequate measure of success without interrogation or significant disruption of the larger network mechanisms they operate within. Finally, investment in investigations of criminal networks remains low. Despite legislative amendments, flora crimes are viewed as low priority by law enforcement, which results in less manpower and fewer resources allocated that further stall the rate at which criminal networks are successfully uncovered and disrupted. - Communities are poorly integrated into responses

Local communities are central to crime-prevention strategies as they can play a major role in either collusion with criminal actors or collaboration with responders to environmental crime. Where communities have a positive relationship with enforcement actors the report found higher successful outcomes with regard to wildlife conservation. Where communities were not involved, and poverty and conflict persisted, conservation work was undermined. - Relevant data is missing

Data on species, population sizes, trade values and market demand, consumer markets, arrests and prosecutions and the geography of trade flows is currently underwhelming and is supplemented only by data on seizures and harvesting incidents. Deficiencies in data that can be used to inform more precise policy and legislation need to be critically addressed in the field to effectively understand the scale of these illicit economies and counter environmental trafficking on the continent. - Corruption presents a pervasive and complex threat

By far the greatest barrier to disrupting these illicit networks remains corruption. State officials, money movers, logisticians, bank managers, accountants, auditors, lawyers and networkers all play vital roles in enabling these systematic illicit networks. These actors often covertly or overtly incorporate their professional roles to gain access to influential people and use this access to facilitate trade and circumvent national laws against trafficking. Where corruption becomes entrenched in affected regions, responders often have difficulty rooting out the core drivers of the illicit trade and holding them accountable to the enforcement of regulations. Often this is a major obstacle to why existing laws are undermined and not effectively implemented. As such, addressing corruption requires intervention at various levels and introducing mechanisms that effectively identify all actors involved in the lucrative trade.

Ultimately, confronting the threat of environmental crimes requires two key approaches. Firstly, increasing accountability and strengthening relationships between local communities as well as law enforcement. Empowering and engaging with communities and providing incentives to protect wildlife, forests or other ecosystems can reduce corruption risk and enhance response efforts making affected regions more resilient to illicit activity. Secondly, improving the global response to environmental crime by actively monitoring trends and providing and sharing relevant data to improve transparency and policy formation.

A key asset to the success of criminal actors is the “gaps” between local, national and international engagements that they operate within. As such, exposing these gaps and fortifying these relationships with transparency is critical to disrupting the devastating impacts of environmental crime.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.