Nigeria, Angola and Ghana are among the top oil producers in Africa. With revenues largely backed by fossil remuneration, the mantra to go green on fuels might sound hollow, but there are plans in place waiting for real action.

At the same time, there are calls for a more realistic “neither one or the other” approach that recognises the inclusion of fossil fuels for Africa’s oil producers in their transition to green economies. This is well articulated by two experienced clean energy policy researchers, Morgan Bazilian and Benjamin Attia both from the Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines, who write that: “The blunt exclusion of all non-renewable energy projects from development finance is an inequitable and ineffective climate strategy that gaslights more than one billion Africans.”

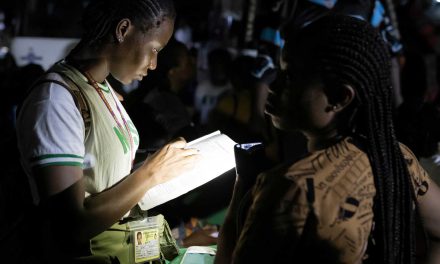

A general view of the location under construction of the new gasoline unit at the Sonangol Luanda Refinery in Luanda on October 22, 2020. Photo: Osvaldo Silva/AFP

Most of sub-Saharan Africa will find “renewable power to be the fastest and cheapest way to expand their generation capacity, but some areas may still need to rely on some fossil fuels in various sectors of the economy as they develop,” they write in The Conversation, October 2021.

At 1.36 million barrels per day, Nigeria is Africa’s number one oil producer. Profits from petroleum exports currently account for 86% of Nigeria’s total export revenue.

Nevertheless, Nigeria has affirmed its pledge to follow the path of low carbon development by 2030, with President Muhammadu Buhari committing during COP26 to achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2060.

The country has ambitious aims to eliminate deforestation by 2030, with carbon emissions below business-as-usual by at least 20%. The country will achieve this ambitious goal by investing in renewable energy transition, clean cooking, water and waste management, nature-based solutions, adaptation and resilience.

Nigeria has demonstrated strong leadership on the continent by making such an ambitious commitment to the UNFCCC 2030 goals, Razaq Fatai, the Policy and Advocacy Manager for international activist and lobbying organisation, ONE Campaign in Africa told Africa in Fact.

And despite the fact that 65% of Nigeria’s government revenues come from oil and gas sales, impressive steps are being taken to decarbonise, says Ifeoma Malo, lawyer and co-founder of Clean Technology Hub in Nigeria in an email interview with Africa in Fact.

There has, for example, been a huge reduction in gas flaring, with policy instruments placing a penalty on gas flaring practices during gas exploration. “One such is the issuing of a Sovereign Green Bond and Climate Bond Certified Sovereign Bond,” Malo says, adding that the focus of these bonds is to finance renewable energy projects across the country.

Fatai also notes, that since 2017, Nigeria has issued a green bond totalling $71m to finance the much-needed transition to a greener and sustainable economic development. “Still, we have not seen a significant outcome. Most of the land restoration/afforestation projects are difficult to track because of unclear project descriptions, and only one of [the bond’s] nine renewable energy projects is operational,” he says.

The plan is to restore four million hectares of degraded land, and Nigeria also plans to give 25 million people access to electricity using decentralised solar energy solutions.

“We are beginning to see a higher electrification rate through the adoption of modular off-grid energy technologies, especially in places that are not connected to the grid. All these are setting the country on a trajectory of increased decarbonisation, Malo told Africa in Fact.

![]()

With gas a less-polluting fuel compared to oil, Nigeria’s federal government has adopted the years 2021-2030 as the decade of gas. Various gas projects are being financed in the country, such as the Ajaokuta-Kaduna-Kano (AKK) gas pipelines and the OB3 pipelines.

But implementing the measures in its new Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs) will require both a strong political will and significant resources, which will be difficult to mobilise, says Fatai.

Nigeria, he points out, has a long history of not honouring and implementing development commitments. It has failed to honour its own 2001 Abuja Declaration to spend 15% of public expenditure on the health sector and has continued to undermine its commitment to the Malabo Declaration in 2014 to transform its agriculture and food systems.

Fatai is worried that Nigeria’s current development model, which is built around fossil fuel, may slow down its pledges to reduce carbon emissions.

“For Nigeria to achieve its ambitious target to reduce carbon emissions, the government will have to move fast, stay committed, and be more transparent in effectively implementing these goals. We need to see clear short-term plans that citizens can track and use to hold politicians accountable,” he says.

Angola, meanwhile has grown into one of the largest oil producers on the African continent, churning out 11.14 million barrels of crude daily since the first commercial oil discovery in 1955 in the onshore Kwanza Basin. The country holds more than eight billion barrels of oil reserves, and the oil sector accounts for more than one third of Angola’s GDP and about 90% of its national exports.

Angola’s Minister of Mineral Resources, Oil and Gas Diamantino Azevedo, has repeatedly publicly stated his support for a “hybrid model”, reiterating that his country has the opportunity to show the world that fossil fuels can play a significant role in moving toward green energy.

The national oil company, Sonangol, is developing an LNG plant that will supply much-needed power and also use associated gas as its primary power source; eliminating gas flaring and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The country is also restructuring Sonangol to include expanded investments in green energy such as a partnership with Eni in Angola to build a 50-60MW solar power plant that is anticipated to come online in 2022.

Some organisations like the African Energy Chamber, which represents the continent’s energy sector, also support the view that without the “power” of oil and gas to finance new technologies and support new initiatives, green energy programmes might fail.

Ghana, produces 189,000 barrels of crude oil per day. Strong output from the Jubilee and Ten oilfields, in conjunction with rising foreign investment in offshore basin development, has granted the country a favourable long-term production outlook.

With new fields coming on stream – in particular, the Aker-operated Deepwater Tano Cape Three Points – oil production is expected to more than double to 420,000 barrels per day by 2023.

On the other hand, Ghana is considered to be one of Africa’s pioneers in respect of the NDCs revision process. The country’s first NDC submission stated that by 2030 greenhouse gas emissions would be unconditionally lowered by 15% and, subject to the provision of external financial support, conditionally lowered by an additional 30%. Ghana could achieve a reduction of 45% of its greenhouse gas emissions should financing become readily available.

Energy researcher Jennifer Cronin of the University College London (UCL) – leading a team of experts, Simon Bawakyillenuo, University of Ghana, and Steve Pye and Jim Watson both from UCL – told Africa in Fact large investment was required for Ghana’s energy sector. “There is a significant opportunity for this to be climate compatible investment,” she says. “As a key economic sector, oil and gas production is likely to continue, but measures can be put in place to reduce the GHG emissions from extraction and processing.”

As a mitigating measure, Ghana has a target of 20% reduction in fugitive methane from oil and gas infrastructure. “Our analysis has shown that Ghana has the potential to meet future energy demands by substantially increasing utility-scale solar PV, along with electricity storage, and also to deploy some wind power and off-grid PV,” Cronin says. A mix of these renewable energy technologies, alongside measures in the oil and gas sector, would enable Ghana to achieve its NDC climate targets and offer significant co-benefits for reliable clean energy access, health and wellbeing, she adds.

Experts agree that transitioning away from fossil fuels also offers the opportunity to reduce the economic risks associated with exporting oil into a diminishing global market. But to achieve greater carbon emission reductions, Ghana’s power sector will require significant investment, with international finance almost certainly required to support this transition.

Ghana is looking at between $9.3 billion and $15.5 billion of investment to implement the 47 updated NDC measures from 2020 to 2030. A Government analysis has found that, using the lower end of those investment figures, 42% would come from domestic sources while 58% would be required from external financial sources and private investors.

All in all, looking at the examples of Nigeria, Angola and Ghana, it is apparent that despite real progress towards meeting their commitments, the road to decarbonise Africa’s oil producing countries is a bumpy one.

Would you like to gain an understanding of your own impact on the environment? Calculate your own carbon footprint here

Munyaradzi Makoni is a journalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He writes mostly on agriculture, climate change, environment, health, higher education, sustainable development and science in general. Some of his work has appeared in Hakai magazine, Intellectual Property Watch, IPS, Mongabay, Nature, Nature Index, Physics World, Science, SciDev.net, The Lancet, Thomson Reuters Foundation, and University World News, among others.