Women’s memories of food offer insights into Mozambique’s liberation struggle

We don’t just taste food. Aromas, visual images, sounds and touch are equally part of our eating experience. Food also evokes feelings. We can experience it with joy but also with displeasure. This sensorily evocative power of food makes it an important site for remembering the past, which in turn influences our relation to food in the present.

There is a lot of important literature in Africa that deals with food security and the biological necessity of eating. However, my research explores how food is connected to remembering and making sense of the past, especially a violent past.

Wugadi and pumpkin leaves cooked with red onion and tomatoes, with dried usipa fish. Photo: Jonna Katto

Food was not my main focus when I set out to conduct research on women ex-combatants’ lived experiences of the Mozambican liberation struggle in northern Niassa province. Yet food and cooking continually came up in my life history interviews with them.

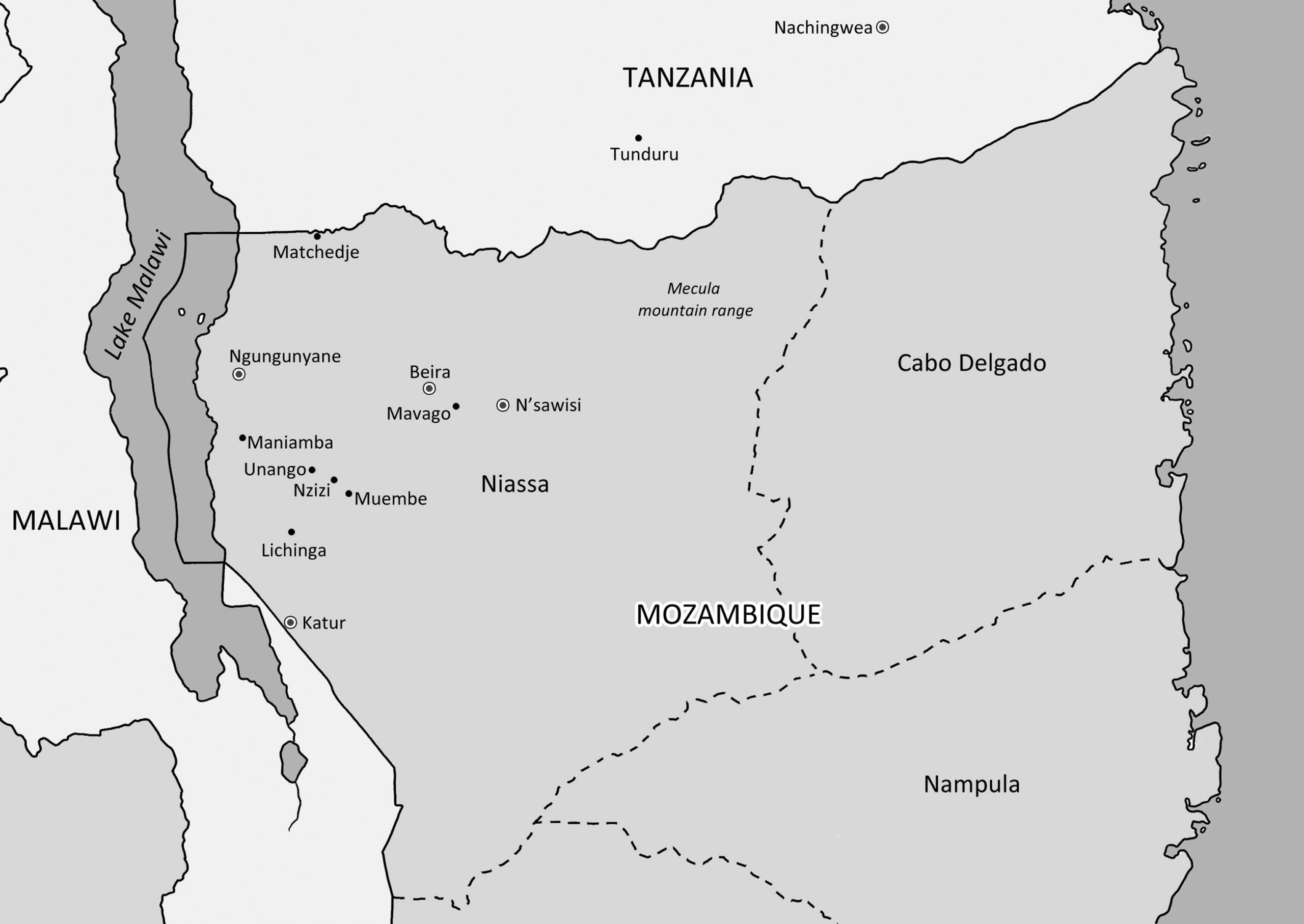

The Mozambican liberation struggle against Portuguese colonial rule was mainly fought in the northern bush thickets. Led by the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), it lasted from 1964 to 1974. The combatants and civilian populations that supported them lived in very difficult bush environments.

Most of these combatants were young people. I was interested especially in Frelimo’s female detachment, many of whom were in their early teens when recruited. Their main job in the military camps in the beginning was to cook for the male soldiers. However, after 1967, they started receiving military training and became comrades-in-arms, mostly mobilising the population to support Frelimo and working in the bush nurseries and hospitals.

I interviewed 34 female ex-combatants [between 2012-14], starting with their childhood memories. This was followed by interviews about their work and lives during the struggle, and lastly their experiences after independence. I also conducted individual and group interviews with 15 male ex-combatants.

Growing up in the rural communities of northern Niassa, most remembered their childhood foodscapes as plentiful. Their principal food was wugadi (stiff porridge from maize flour) with an accompanying dish of beans or the leaves of pumpkins, beans or sweet potatoes, boiled with salt.

But war disrupted normal village life. In peacetime, seasonal changes brought different foods, the rainy season associated with the joy of a new growing cycle. But in the time of war, the ex-combatants remembered rain intensifying the painful conditions of the bush.

Food became a constant struggle. Due to heavy bombardments by the colonial troops, the cultivation of crops was extremely difficult. There were periods in which the guerrillas experienced intense hunger and were forced to eat things considered inedible during peacetime.

One ex-combatant, Rosa Mustaffa, remembers how the guerrillas were forced to eat just about anything that crossed their path, just to “get rid of the feeling of hunger”. Others observed the monkeys to see which roots they were digging up. What didn’t kill the monkeys was considered suitable for humans too.

Food became associated with danger. The “things of the bush” could kill a person. Helena Baide explained how the guerrillas cooked poisonous fruits and roots to eat, taking the whole day and changing the cooking water continually. Ash was added to the water to mitigate the bitter taste associated with poison.

Honey and game meat were the main sources of nourishment, but hunting posed a danger as it could alert the enemy to their location. The guerrillas learned to farm and cook differently in wartime. They cultivated small, dispersed fields on river banks, partially under the cover of trees. Hearing the noise of aeroplanes, they would flee to nearby bunkers. Or they farmed under the moonlight. The noise of the pestle and smoke from cooking fires could also draw the enemy’s attention. Often cooking was done at night under the cover of trees.

Niassa. Frelimo’s principal military bases in Niassa during the war are marked with white circles. Map: Noora Katto

For many, the promise of liberation carried food-related dreams. This is the future that Assiato Muemedi spoke of imagining during the war: “I will cook with cooking oil, build a house and open a big field to eat food with my children.”

After being demobilised, the transition to civilian life was easier for some than for others. Many of the young female ex-combatants had been forced to leave home so young that they had not learned, for instance, how to cook and farm properly. Those who were older found it easier, and they spoke of continuing the work of their ancestors, cultivating crops such as beans, maize, potatoes (regular and sweet) and cassava.

For most ex-combatants, food in peacetime has in many ways been a “liberating” experience of pleasure and fulfilment. Many relish the freedom to cultivate, to eat together in peace with family or to buy basic items from nearby markets. This has helped to forget the bad things they ate in the bush.

Yet eating was not the only positive experience. The idea of “eating badly” is, in the ex-combatants’ accounts, strongly associated with their current experiences of social division and inequality.

During the struggle, Frelimo’s political talk of unity, freedom and a future good life gave the combatants strength to endure hardship. And they remember that, while they ate badly, they ate together and shared the little they had.

Yet, these days, the former comrades-in-arms of the Niassa forests are divided by space, education and class. Most of those in leadership were transferred to Maputo after independence as part of Frelimo’s state-building project.

The ex-combatants in Niassa criticise the elite in Maputo for eating well at the expense of the majority of their former colleagues, who are unable to participate in the new consumerist modernity. In this context, it is the imagined diets of the nationalist elites that have come to symbolise freedom and liberation.

The official history of the Mozambican independence war is a linear narrative that proclaims the happy ending of liberation. Yet this narrative ignores the violence that is intimately part of its lived history.

Studying the ex-combatants’ food memories shows how the history of liberation is not a closed process. They continue trying to make sense of their past and present experiences (and even future anticipations) of violence. Food plays a role in this.

Even today, bodily memories of food-related violence persists. So while food again animates their senses, liberation has, for many, a slightly bitter aftertaste.

This article is reproduced courtesy of The Conversation, where it was published on 8 November, 2020. Katto received funding for this research from the Finnish Cultural Foundation. She is affiliated with Ghent University and the University of Helsinki.