For most rural African girls, menstruation presents a dilemma: either attend lessons and face embarrassment, coupled with self-discrimination, or remain at home to nurse their monthly periods.

The Primary School Education Advisor (PEA) for Kasiya Zone in Lilongwe, Nairobi, Charles Ndeketeya, says he has had 40% of his female learners absent from his class in a week, due to menstruation issues.

“This is a cultural taboo,” says Ndeketeya, a rare male teacher at the centre of sensitive feminine issues. “Girls haven’t been free to communicate their issues to teachers, or anyone. They feel embarrassed and therefore self-discriminate.” But, Ndeketeya says, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Days for Girls and Malawi Girl Guides Associations (MAGGA) have helped to break down taboo barriers and assist girls with reusable sanitary pads.

A United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report titled ‘Puberty Education and Menstrual Hygiene Management’ says one in 10 girls in sub-Saharan Africa miss school while on their period. Another study in Ethiopia ‘We Can’t Wait’, a report on sanitation and hygiene for women and girls, found that 50% of girls miss between one and four days of school every month due to menstruation.

Fourteen-year-old Eliza, a Kasungu-based standard six (grade 8) learner, says: “Periods make me uncomfortable. Since the day I began menstruating, I was told this is my secret and no one else should know about it. I use either pieces of cloth (chitenje), blankets, or old, worn-out cloths for menstruation. These are washable but are supposed to be dried at a place no one, especially men around the house, can see. No one is even supposed to see the leaks.”

“They produce a bad odour,” she continues. “It’s been difficult for me to attend classes; at times I’ve developed blisters around my inner thighs, making it difficult for me to even move. I also have to frequently change and wash the soiled pieces of cloth … it is hard to change them in a school set up.”

To make matters worse, Eliza says, most girls do not have proper underwear but are forced to use a traditional kit, a piece of cloth tied around their waist to hold in place the other piece of cloth used for menstruation, which serves as a substitute for a disposable sanitary pad.

Disposable sanitary pads are too expensive for the majority of Malawian girls and women, says Esther Mhango, a Mzuzu resident. “I’ve seen these things in shops but they are expensive. Cloth pieces do the trick although they are unreliable and unpredictable. One can leak at any time,” she told Africa in Fact. The average price of a packet of 10 sanitary pads in Malawi is K700 ($0.86) and most women require at least two packets to have a comfortable period.

Malawi country representative for Days for Girls Eunice Banda says traditional beliefs have also contributed to menstruating girls missing out on school. She cites, for example, the belief that girls having their first period should be locked up in their homes for a week without talking to or seeing anyone. “They are given their food and they only come out to go to the toilet or bath,” she told Africa in Fact. “It is believed that if they defy this, they will cast a spell on their fathers and others.”

Banda says her organisation has helped 6,000 schoolgirls in Rumphi, Mzimba, Kasungu, Lilongwe, Mangochi, Neno, and Balaka districts with reusable sanitary pads and underwear. The Days for Girls kit includes eight liners, two menstrual liner shields, two sets of underwear, soap, a washcloth, a tracking calendar, and a waterproof carry pouch (to carry the kits or soiled liners).

“Since many schools do not have water, they keep the used liners in the carry pouch to wash at home,” Banda explains.

Banda says her organisation’s interventions are multifaceted in that they also work towards addressing puberty ignorance among adolescent girls. “Most of them don’t know how their bodies function,” she says. “We educate them about their hormones and how they affect their menstrual cycle. We also advise them how to care for themselves so that they are not embarrassed by bad odour.”

The organisation engages with communities through interface meetings with traditional leaders, parents, and mother groups. It also engages with men through a programme called Men who Know. “We want them to be aware of their bodies and that of girls so that they are supportive and treat women with dignity,” Banda says. “This way we ensure the girl is safe at school, in the community, and everywhere.”

Senior Chief Khongoni of Lilongwe says times have changed and she does not tolerate girls using menstruation as an excuse for being absent from school. “NGOs and mother groups are trying hard to help keep girls in school,” the chief told Africa in Fact. “We can see the difference in areas where there are no engagements such as these. We urge supporters to reach out to as many girls as possible.”

The organisations are also training mother groups on how to make reusable pads and sharing the knowledge with the girls. In Malawi, mother groups – a grassroots group of women – help in advancing girls’ education by giving advice on female concerns, rescuing them from child marriages and helping to keep them in school.

The Cova Project, an Australian charity whose core purpose is to provide access to education, and dignity to menstruating girls and women, is also helping Malawi’s school girls by distributing reusable menstrual cups made from 100% medical grade silicone, which can be used without a change for up to 12 hours. The organisation provides educational material tailored to specific cultural norms and language through locally run partnerships in Uganda, Malawi, Ghana, and Liberia based on community and peer support.

Cova Malawi’s menstrual health consultant and registered nurse, Cassy English, says that absenteeism due to menstruation is prevalent in the country. “The data, though, is poor, so the numbers are probably much higher,” English told Africa in Fact. “It depends on where are you in Malawi, of course,” she says. “Rurally, we see as many as 65% of girls missing school due to a lack of menstrual health and hygiene options. Even one lesson missed due to a naturally occurring bodily function is too many.

“In Malawi specifically, we will reach close to 5,000 girls and women by the end of 2022, primarily in the northern region, with smaller outreach in the south. Our data has shown an increase in girls not only remaining in school month after month, but overall daily attendance has improved,” she says.

Principal Secretary in the Ministry of Education Science and Technology (MoEST) Chikondano Musa agrees girls’ absenteeism is due to several factors, including dignity issues attached to menstruation. MoEST, in partnership with NGOs, has been building washrooms at schools, that also have changing rooms.

Mother group chairperson Lutia Dawe of Mazonga village, in the traditional authority of Khongoni in Lilongwe, acknowledges that efforts to provide menstruation kits to girls has made a difference in absentee rates, but believes more must be done. “Only five out of 10 schools benefited from this assistance,” she told Africa in Fact. “The absenteeism challenge is still alive in the remaining schools.”

Earlier this year, in a bid to promote girl child education, the Malawi government removed duty and excise tax on sanitary pads. “Government has listened to the contributions that came from various stakeholders and has done this as one way of supporting general feminine hygiene,” said the Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs Sosten Gwengwe.

But both Banda and English say that while this is helpful, pads are still expensive because most retailers have not reduced the prices. Adds English: “In the communities we work, pads – even untaxed – are unobtainable. Our baseline data collected in schools has shown no change in the ability of girls to purchase one-time-use pads. This is a step in the right direction but with the economy and other basic human rights still not met more needs to be done than this. Options should be free, accessible, and of high quality. This is a gender tax that only women face.”

Adds Banda: “While we applaud the government for removing the tax, this does not trickle down to the beneficiaries. We continue to lobby the government to reduce the price of materials used to make reusable menstrual pads.”

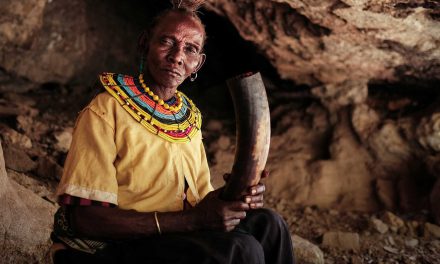

South African menstruation activist and self-styled Minister of Menstruation, Candice Chirwa

If someone had told me that at the age of 10, when I had just started my period, that I would be a menstrual activist fighting to change the disempowering narrative surrounding periods in South Africa, I would have laughed. I had little to no education about menstrual health, but I know that if there had been someone like the Minister of Menstruation when I had started, things would have been completely different.

If someone had told me that at the age of 10, when I had just started my period, that I would be a menstrual activist fighting to change the disempowering narrative surrounding periods in South Africa, I would have laughed. I had little to no education about menstrual health, but I know that if there had been someone like the Minister of Menstruation when I had started, things would have been completely different.

On any day, more than half of the population between the ages of 15 and 49 are menstruating worldwide. It is estimated that more than 800 million women and girls have their periods every month. And for me, although I find my period to be a minor nuisance, I, fortunately, am afforded the ability to manage my period safely and hygienically. I had the benefit of having a conversation (very awkward, but a conversation nonetheless) with my mother, who talked to me about it when I was 10 years old. I went to a school that covered menstruation from a biological point of view, and I was lucky to have access to a private toilet with a sink, dustbin, and menstrual health products.

Now, if you’re reading this and you’re a person who menstruates and realise that you too had the same experience, then trust me when I say our period experience is a privileged one. I want you to reflect for a second on what you would do if you did not have any access to toilet paper. You’d probably think about using a piece of paper or cloth. But I further ask, what if you didn’t have access to paper or cloth? And this was your reality every single day? Now, if you didn’t have access to a sanitary pad, a tampon, a menstrual cup, a reusable pad, or period underwear, what would you use? A cloth? Newspaper? Tissue? A sock? That bleeds through too quickly. Sand? Leaves? Used rags? That can cause an infection.

So, what is the alternative for a young girl who has limited access to period products? She stays at home. And the consequences of not having access to period products means that a young girl will miss one or more days of school, and ultimately, this impacts her education. This means that many people who menstruate around the world will, at some stage in their life, sacrifice school, work, and social activities.

Menstruation is a shared experience among women and girls. And yet it is a widely stigmatised issue. It is a topic that is still met with awkwardness and silence, and is only spoken about behind closed doors. This silence is implicated in the lack of policies within educational programmes concerning menstruation, or that address period poverty overall. If it became law that period products were free of charge to the communities that needed them, and were easily accessible along with empowering education, then a period positive world may become a realistic idea.

There is more to be done, especially at the state level. Our governments can, and should, play an important role in the destigmatisation of menstruation. The perception of menstruation is affected by government policies in education, development, business, taxes, and healthcare. Governments need to recognise that period products are essential items and do not have to break the bank. Beyond providing access to products, we also need better puberty, sex, and period education for young people in schools, so that young menstruators are not reduced to suffering alone in silence.

The Minister of Menstruation aka Candice Chirwa is an academic, author, TEDx speaker, podcaster, and social entrepreneur. Candice has an avid interest in educating the youth on menstrual health and management, and brings eduliftment with her award-winning NGO, QRATE.

Josephine Chinele is multi-award-winning international journalist. She has worked as a news, features and investigative journalist for newspapers, radio and television platforms in Malawi, Tanzania and South Africa. Josephine has also been awarded several prestigious journalism fellowships in the area of HIV and AIDS, health and human rights among others. She is also a biomedical HIV prevention advocate.