Recent conflicts between pastoralists and farmers are prompting some African countries such as Nigeria to seek to curtail the Fulani’s ancient itinerant culture

As a boy growing up in rural Taraba state in north-east Nigeria, Mohammed Bello recalls roaming the bushes with his father in search of fodder for the family’s herd of cattle. Each day, Bello and his brothers started the morning by checking the animals for ticks, before trekking distances to feed them.

For centuries, people of the Fulani have befriended and sometimes even settled into the communities through which they herd their livestock. In communities they visited, locals allowed their animals to feed on leftover millet husks in harvested farmlands; meanwhile, the herders kept off farms that had crops. The system benefited both groups as the farmers used the animals’ dung as manure.

“To an average person, the cow is meat; but to a Fulani man, the cow is his culture, the cow is his history and the cow is his identity,” Bello, a former secretary-general of the Confederation of Traditional Herder Organisations in Africa, told Africa in Fact.

Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari, a Fulani, had 270 cattle on his farm when he came to power in 2015.

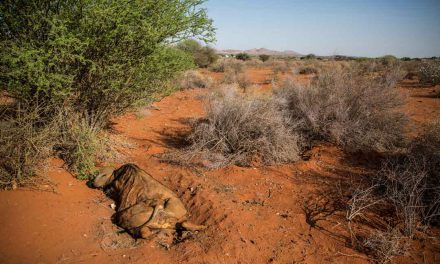

Across Africa, that culture is increasingly being rejected. The camaraderie between migrant herders and indigenous communities has largely faded. Instead, conflict over resources such as land and water has fuelled deadly clashes between both groups. In the first half of 2018, at least 1,300 people were killed in Nigeria in violence linked to armed herders, the International Crisis Group said in July. Similar killings have occurred in other West African countries like Ghana, Mali and Ivory Coast.

With violence growing and environments changing, some African countries such as Nigeria are seeking to curtail nomadic cattle husbandry and in doing so reshape one of the continent’s oldest cultures. Nigeria’s federal government has proposed ranching to allow pastoralists to feed their livestock without having to migrate. In some states – such as north-central Benue, worst hit by the violence – laws banning open grazing and herd migration have been enacted. In Ghana, open grazing is banned countrywide, and the government has shown willingness to enforce the ban.

Some critical voices have denounced such bans as an attack on an ancient culture that brought a range of ethnic groups into regular contact. “These laws are oppressive and negative and are fundamentally against our culture as Fulani pastoralists,” Nigeria’s Vanguard newspaper quoted the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association, an influential group promoting the welfare of Fulani pastoralists in Nigeria, as saying in June.

The Fulani’s nomadic pastoralist lifestyle goes back more than a thousand years, says Sadiq Radda, a professor of sociology at Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria. The culture has always been centred on raising livestock – mostly cattle, sheep and goats. Originally located in the Sahel, the Fulani migrated southwards over several centuries leading up to 1900 in search of pastures for their herds and settlements for their families. As they wandered, they and their culture spread to various parts of west and central Africa.

According to the Combating Terrorism Center, an academic institution at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, about 75% of the estimated 25 million Fulani continue to follow the traditional semi-nomadic, cattle-rearing lifestyle. With populations growing and available land declining, their lifestyle is bringing them into conflict with settled farmers. In Nigeria in particular, the seasonal migratory pastoralism flourished for decades and brought groups of variant cultures together. The Fulani learnt crop farming from their hosts, while local communities adopted aspects of pastoralism, with the exchanges enhancing communal peace.

“The Fulani nomadic culture has been tremendously affected by cultures (it has) met. (It) ha(s) also affected other cultures,” Tukur Muhammad-Baba, an expert in the culture and professor of sociology at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University in Sokoto, Nigeria, told Africa in Fact. According to Muhammad-Baba, who has extensively studied the Fulani nomadic culture, that relationship created a “cultural infusion” in Nigeria’s north and middle belt.

In rural Taraba, where Bello grew up, his father and other herders would first send out scouts to neighbouring and distant communities to search for grasses for the cows – and, importantly, to check that they would be welcome. Where they had positive feedback, relationships with local communities were explored, and with that often came friendship. For the Fulani, the driving force was the welfare of their livestock. “The Fulani man does not want the land, he only wants the grass for his cattle,” says Bello, who now works at Nigeria’s Federal Character office in Abuja.

Fulani cattle herded through the streets of Abuja, Nigeria. Photo: Ini Ekott

When he was still a boy, a Fulani male was regarded as wealthy only if he owned at least 100 cows, Bello said; when his father died, he left at least 500 cattle. Despite the greater availability of education since then, a Fulani man’s wealth is still measured by the number of cows he owns. (When President Muhammadu Buhari, a Fulani, came to power in 2015, his office said his farm had 270 cattle. Under public pressure, he released some details concerning his assets when he took office, but has refused to provide further information since.) “People think it is a backward culture, but to the average Fulani the size of his herd determines his status in the community,” Bello said. “If you don’t (own) a cow, nobody knows you.”

In recent years, climate change, urbanisation, and population growth have created a toxic blend that has turned herders and farmers against each other. Confrontations over damaged crops or stolen cows are typically followed by violence and reprisal attacks. In its July report, the International Crisis Group said violence linked to armed herders in Nigeria was six times deadlier than attacks by the Islamist group Boko Haram.

The government says it is serious about ending the incessant conflicts and reforming the nomadic culture. It’s a problem that has defied multiple administrations since the end of military rule in 1999. Buhari’s government, which initially argued in favour of nomadic grazing, is now planning towards a future that will see pastoralists confine their activities to ranches, and has identified swathes of land of various sizes across 94 locations in the 10 states as part of a pilot project to encourage the change. “This is the only way out of the conflict,” Agriculture Minister Audu Ogbeh told the Daily Post newspaper in February this year. “We either ranch, or banish cattle from Nigeria.”

The plan has not gone without challenge. Some states have donated land for the project while others have deplored it, arguing that it would use public land and financial resources for private businesses. Some have said that the policy does not take into account the fact that cattle breeds common in Nigeria are unsuitable for ranching due to their low growth and high consumption rates, which make the animals too expensive to raise. Still, others have questioned the practicality of the ranching approach for a centuries-old culture. “The Fulani way of life is not something you can transform overnight,” says Radda, himself a Fulani. He added that for many years, different administrations had allowed the Fulani lifestyle to continue without addressing the problem.

Clearly, the demand for sudden change will compound “a major mistake” with another one. But Radda also accepts that the Fulani themselves will need to consider changes to their culture for the sake of peace. “If a culture does not address your requirements, then there is no need to retain it,” Radda says. “Culture is meant to serve man, rather than man serving culture.”

Previous attempts at ranching were unsuccessful. Experts say they failed largely because of the huge capital investment required in the infrastructure and services necessary for a more sedentary lifestyle. Those unsuccessful attempts were made in the 1970s by the states of Kaduna and the now defunct Gongola, and the fact that the move was not executed by the central government partly explains the funding difficulty the programme faced. This time, the federal government is driving policy and has detailed an ambitious plan to develop ranches at the cost of 179 billion naira ($497 million) over 10 years. The federal and participating state governments are to spend 70 billion naira in the first three years.

Muhammad-Baba agrees that government support is an important first step in getting the policy right. But he urges that it will be important to inform herders about the impending change to their ancient way of life and to provide them with the kind of education they will need for a different, more settled lifestyle.

Like every culture, the Fulani’s nomadic lifestyle is facing changes to its environment, both human and natural. The government says Nigeria loses about 400,000 hectares of land every year to encroaching desert in the north. Yet, while the country’s land mass has become smaller, its human population has grown from 52 million in 1963 to nearly 200 million, Information Minister Lai Mohammed said in May at a town hall meeting, where he defended the government’s response to the herders-farmers crisis.

Mohammed also said that Lake Chad, which waters parts of north-east Nigeria alongside neighbouring Niger, Chad and Cameroon, has now shrunk from 25,000 to 2,500 square kilometres. “At its peak, it was supporting 35 million people from many countries in Africa,” he was quoted by the Leadership newspaper as saying. “Today, most of those people have moved south in search of greener pastures, further exacerbating the contestation for increasingly scarce natural resources – and the resultant friction.”

As Muhammad-Baba sees it, the Fulani will have to adapt to their changing circumstances. “Nature is beginning to withdraw some of the conditions that supported them,” he says. “You cannot preserve a culture; culture is a living organism.”

Ini Ekott is the deputy managing editor at Premium Times, Nigeria. He has researched and written extensively on governance and leadership in Africa. He is a former Wole Soyinka investigative reporter of the year, and was a member of the global team of journalists that conducted the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers reporting