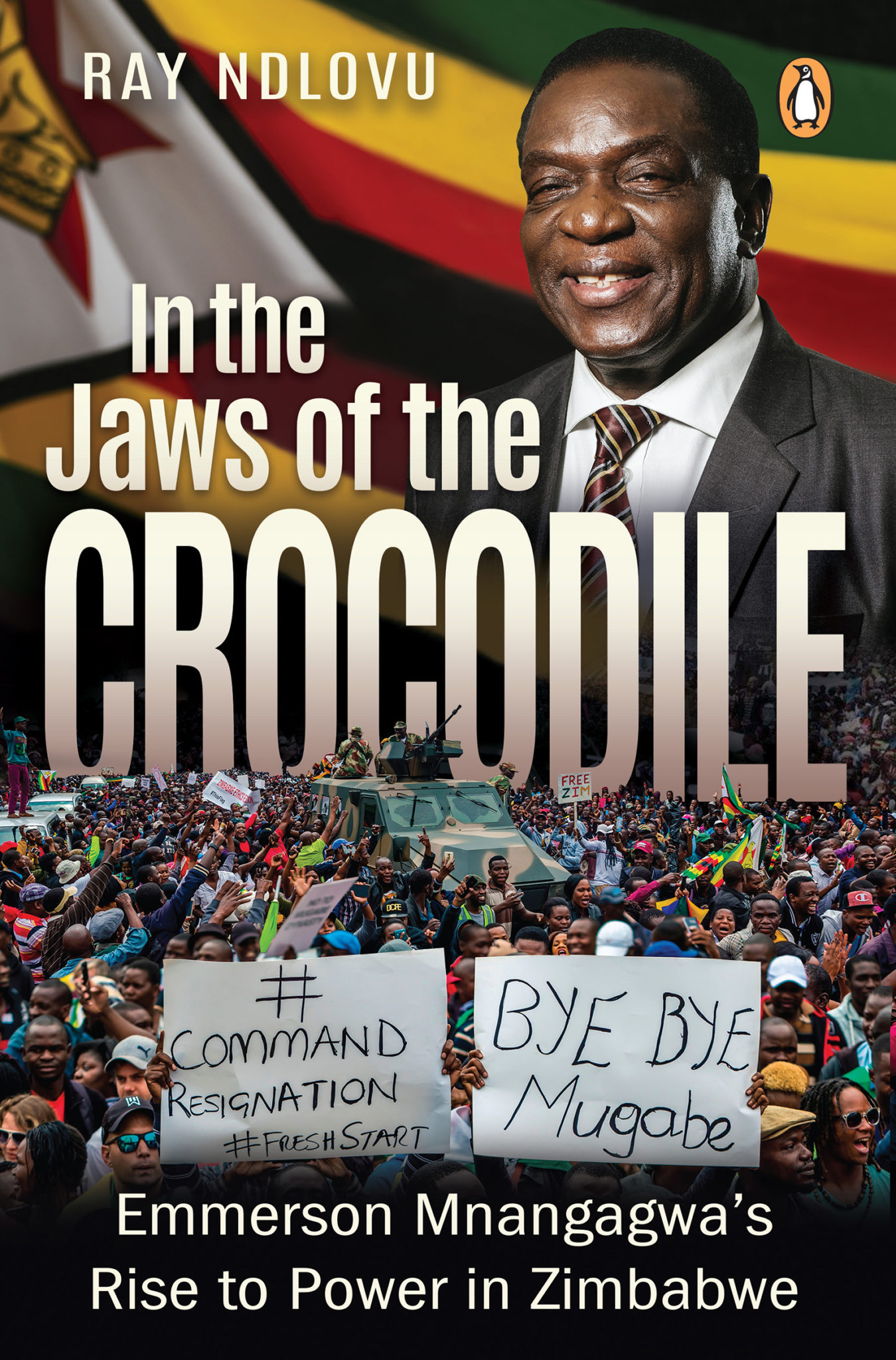

Military and police presence in Harare during protests against former president Robert Mugabe, 18 November 2017. PHOTO Graeme Williams

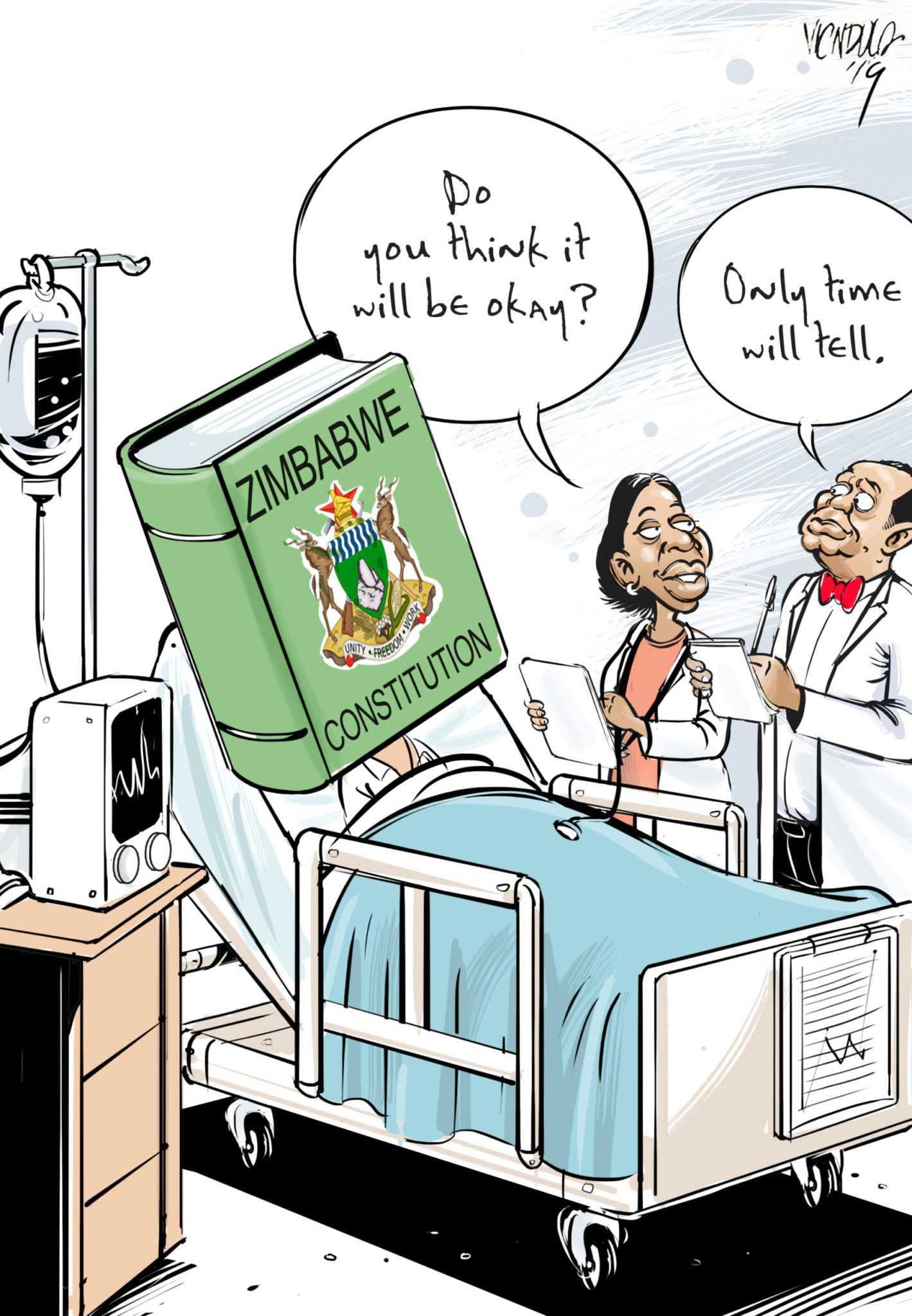

There appears to be some light at the end of Zimbabwe’s dark constitutional tunnel but only time will tell if the gains made will gather pace

Since its founding as a modern state in 1890, Zimbabwe has had a tumultuous political and constitutional history. This history includes an illegal constitutional order declared by white settlers in 1970 in the context of an equally illegal Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) whose strategic interest was to preserve power in “responsible” white hands and defer black majority rule into the indefinite future.

The phenomenon of rule by law rather than rule of law first reared its ugly head then and has become a defining feature of post-independence governance, first under the 1979 Lancaster House Constitution (LHC) and secondly under the new Constitution minted in 2013. Both before and after independence in 1980, the iron law of Zimbabwe politics has been power politics, sometimes in its soft form and other times as hard power politics.

Power politics meant that whenever the country’s constitution was deemed to be a hindrance to the maintenance and exercise of power it was amended. Thus, the LHC was amended not less than 19 times in less than three decades, with the 20th amendment ushering in the 2013 Constitution, officially named Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (no. 20) Act of 2013.

A country’s constitution specifies who will exercise power and how, as well as defining the obligations and rights of both the state and its citizens. But the mere existence of a constitution, no matter how elegant, does not guarantee its observance unless it is undergirded by an ethos of constitutionalism.

The ultimate goal of constitutionalism is to limit governmental power as contemplated by the state constitution and the supporting statutes and regulations (Currie et al 2002). Specifically, it places limits on the organs of government (Roth 1993: 283).

The Lockean concept of limited government is usually linked to the rule of law, whose anchor is the concept that the constitution alone provides the source, and thereby the limitation, of governmental authority. In short, constitutionalism means the letter of the constitution is clothed in the spirit of constitutionalism. The divergence between the letter and the spirit of the constitution has been a cardinal feature of Zimbabwe’s governance since the country’s first constitution in 1898.

Although the 1979 LHC provides the starting point on debates about constitutionalism in post-independence Zimbabwe, it did not embody democratic values and this caused Zimbabwe to have “empty” constitutionalism rather than “substantive constitutionalism” (Freedom House 2012: 5).

After all, from the very outset, the independence constitution, defective at birth by among other things not being justiciable, was further undermined by a pre-independence state of emergency – retained until 1990 – that allowedpreventive detention and restrictions on freedom of movement.

A lawyer holds a placard as she takes part in a “March for Justice” toward the Constitutional Court in Harare on January 29, 2019, to call for restoration of the rule of law, respect of human rights as well as the country’s Constitution. (Photo by Jekesai NJIKIZANA / AFP)The darkest part of Zimbabwe’s history, Gukurahundi (1982-1987) – which then president Robert Mugabe later called a “moment of madness” in which an estimated 20,000 civilians died, was executed by the state in flagrant vitiation of citizen rights and liberties.

Within the first decade the national constitution had been mutilated multiple times with each amendment tending to amass power in the executive, which proceeded to use the supreme law as a weapon in raw power politics. It was a far cry from Douglas Greenberg’s view of constitutionalism according to which:

“Constitutionalism is a commitment to limitations on ordinary political power; it revolves around a political process, one that overlaps with democracy in seeking to balance state power and individual and collective rights; it draws on particular cultural and historical contexts from which it emanates; and it resides in public consciousness”(1993, xxi).

Rule of law was displaced by rule by law, whereby the LHC and a supporting battery of statutes and regulations are used as weapons in a Machiavellian game of power politics. State-centred predation, egregious abuse of human rights, politically motivated violence and intimidation, all done with impunity, started rearing their ugly heads in the first independence decade, took a turn for the worse post-2000 and have become entrenched since then.

In less than three decades the independence constitution had been amended 19 times, making it virtually unrecognisable from the original document. Under the watch of the tattered Constitution, rule by law reigned, manifested in many events, including the violent Fast-Track Land Reform Programme that was in fact ruled unconstitutional by the then white chief justice, who was quickly “retired” and replaced by an indigenous chief justice who promptly reversed the earlier ruling, making the programme constitutional.

Numerous other cases of unconstitutional acts were committed during the life of the LHC, including the infamous Operations: Murambatsvina (1985), which violently displaced thousands of poor families in urban areas; Mavhoterapapi (April-June 2008) – the violent inter-election presidential run-off campaign; and Hakudzokwi (late 2008), an operation by security forces to flush out “illegal” diamond miners in the Marange alluvial diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe.

An intriguing era in Zimbabwe’s political development was the tripartite Government of National Unity mandated by an elite-negotiated political settlement called the Global Political Agreement that itself required a constitutional amendment (Constitutional Amendment No. 19) of 2009. The shaky constitutionalism between 2009 and 2013 led to the establishment of fragile institutions on healing such as the Organ on National Reconciliation, Healing and Integration (ONRHI) whose only legacy was a mantra of “peace begins with me, you and all of us”.

It also failed, until 2014, to operationalise the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission to fight impunity as contemplated by international norms such as the Paris Principles on National Institutions. This was notwithstanding the fact that the growth of constitutionalism depends on strong national institutions. The GNU also declared blanket amnesty on perpetrators of human rights crimes.

After a four year constitution-consultation process, the LHC was replaced by the 2013 Constitution, a vastly more progressive social contract, which received popular legitimacy in a referendum in which 95% of the voters endorsed it.

Under Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution there is a clear separation of powers and some checks and balances on state institutions; it entrenches constitutional sovereignty and constitutional democracy as well as entrenching some crucial aspects, which limit the exercise of state power such as popular sovereignty and a broad Declaration of Rights modelled on declarations in the South African Constitution (Hofisi 2018).

The new supreme law guarantees freedom from arbitrary detention, rights of assembly and association, freedom of expression and the media, as well as “free, fair and regular elections”. Women are key beneficiaries, with assured equal access to universal rights, even where these might conflict – as they often do – with customary rules and traditions. Significantly, a constitutional court was established as the final legal authority on matters of a constitutional nature. As Michael Bratton commented soon after the enactment of the newly minted Constitution, “If implemented, numerous provisions of the new supreme law … promised to begin to dilute the discretion of an all-powerful executive presidency”.

The new supreme law guarantees freedom from arbitrary detention, rights of assembly and association, freedom of expression and the media, as well as “free, fair and regular elections”. Women are key beneficiaries, with assured equal access to universal rights, even where these might conflict – as they often do – with customary rules and traditions. Significantly, a constitutional court was established as the final legal authority on matters of a constitutional nature. As Michael Bratton commented soon after the enactment of the newly minted Constitution, “If implemented, numerous provisions of the new supreme law … promised to begin to dilute the discretion of an all-powerful executive presidency”.

Bratton, however, hastened to warn that “the promulgation of a new constitution did not, in practice, guarantee a culture of constitutionalism” (2014, 183). Indeed, before the new Constitution celebrated its fifth anniversary it had been amended (Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Act of 2017, to restore the LHC provisions for appointment of the chief justice, deputy chief justice and the judge president of the High Court; appointments will now be made by the president after consultations with the Judicial Service Commission. So much for constitutionalism!

Again, on the positive side, the new social compact protects the people’s sovereignty in the main preamble. Accentuating popular sovereignty through the social or people’s contract, the “We the People of Zimbabwe” clause is also given credence by other provisions, which show that the authority of the three pillars of the state – the executive, judiciary and legislature – is derived from the people.

Importantly, too, given the history of centralised power in Zimbabwe, the Constitution has a second preamble that speaks to the need for central power to be devolved to the lower tiers of government, such as provincial and metropolitan councils, and rural or urban local authorities.

A landmark feature of the new Constitution is that it has a justiciable Declaration of Rights (Chapter four), which entrenches various political and individual rights that are necessary in shaping constitutionalism.

Importantly, amending this chapter requires a popular referendum rather than a simple two-thirds majority as is the case with other constitutional amendments. The pros of this is that courts in the post-2013 period have been frequently using constitutional provisions to thwart security institutions such as the Zimbabwe Republic Police from arbitrarily depriving political parties, social

movements and human rights activists from exercising the freedoms and rights such as those relating to petitions, demonstrations and the right to vote. Most notably, the Constitutional Court (ConCourt) recently struck off some repressive provisions of laws such as the Public Order and Security Act (POSA). The ConCourt suspended the operation of the order to enable the government to align POSA with the Constitution as envisaged under constitutional separation of powers.

Further, the courts have proactively protected the repositories of state power, the people, through judgments that obligate the state as the primary duty holder to protect, promote, respect and fulfil fundamental human rights. Key judgments include those that outlawed provisions of statutes of limitation such as the Police Act and the State Liabilities Act, which imposed stringent requirements on aggrieved citizens who wanted to claim damages or restitution from the state for acts committed by state functionaries. For instance, statutes disbarred citizens from attaching state property and, ultimately, claims against the state before 2013 were futile.

Even the November 2017 military intervention, dubbed Operation Restore Legacy was “done” using the Constitution as the reference point. The Constitution is gradually informing the process of aligning laws with the supreme law.

It also enables citizens to use strategic litigation to promote constitutionalism and the rule of law using national courts. While the failure to implement devolution remains a scar on constitutionalism post-2013, there have been deliberate moves to promote vertical accountability through the arrest or prosecution of executive functionaries accused of corruption.

Indeed, there appears some light at the end of the dark constitutional tunnel. But only time will tell whether the wind of constitutionalism blowing, albeit still hesitatingly, will gather pace and robustness.