To achieve inclusive governance in an African context, it is quite clear that a capable, caring, and effective state is essential. The role of the state in driving meaningful economic transformation has become even more pronounced in the aftermath of the pandemic. However, the current capabilities of government entities and agencies across the continent leave a lot to be desired, with a lack of technical skills and know-how often constraining their ability to function effectively. Solving this problem will require programmes and policies that attract technocrats into the public service, as well as a wholesale strategy to professionalise service delivery.

As noted in its 2018 diagnostic on governance titled ‘Public service in Africa’, The Mo Ibrahim Foundation paints a bleak picture of state capacity across the continent.

“The average African public service displays a lack of capacity. African public services remain relatively small employers, with higher costs than in other regions and large country disparities. Public employees in Africa are on average better educated than in the private sector, but they are also twice as old on average as the population they serve. Job motivation is mainly around job security. Mobility within or outside public service is almost non-existent, political dependence is strong, working equipment is scarce, corruption is among the highest at the global level, ‘ghost public servants’ populate many services, while too many of the best-trained employees choose to work abroad. Building public services in post-conflict settings, often from scratch, represents a specific challenge.”

Medical staff prepare to move victims a day after 20 students lost their lives in a swimming accident at Kintampo waterfalls, a popular tennis spot in Ghana in March 2017. (Photo: Cristina Aldehuela/AFP)

While Africa is not a country and each public sector and civil service has its own distinctive features, there are several common elements from this analysis which permeate across the continent. Moreover, in the aftermath of the pandemic, governance pressures have intensified, as human and financial resources have come under significant strain. In a context where governments are required to expand their reach and relevance, the continuation of weak governance and ineffective institutions presents sizeable challenges for countries whose young populations are increasingly agitating for better governance. These pressures have been further exacerbated by the emergence of new and complex threats, increasing state fragility, and declining levels of public trust in governments across the continent.

Such trends place the spotlight firmly on reform and how governments can reconfigure to become fit for purpose. In Africa, where the continent’s progress is largely constrained by analogue leadership for a digital age, governments now need to dramatically improve their capacity and capability. Doing so will require reimagining a new social contract that adequately caters to the needs of the continent’s young population, who are increasingly demanding greater access, resources, and opportunities than they are currently receiving.

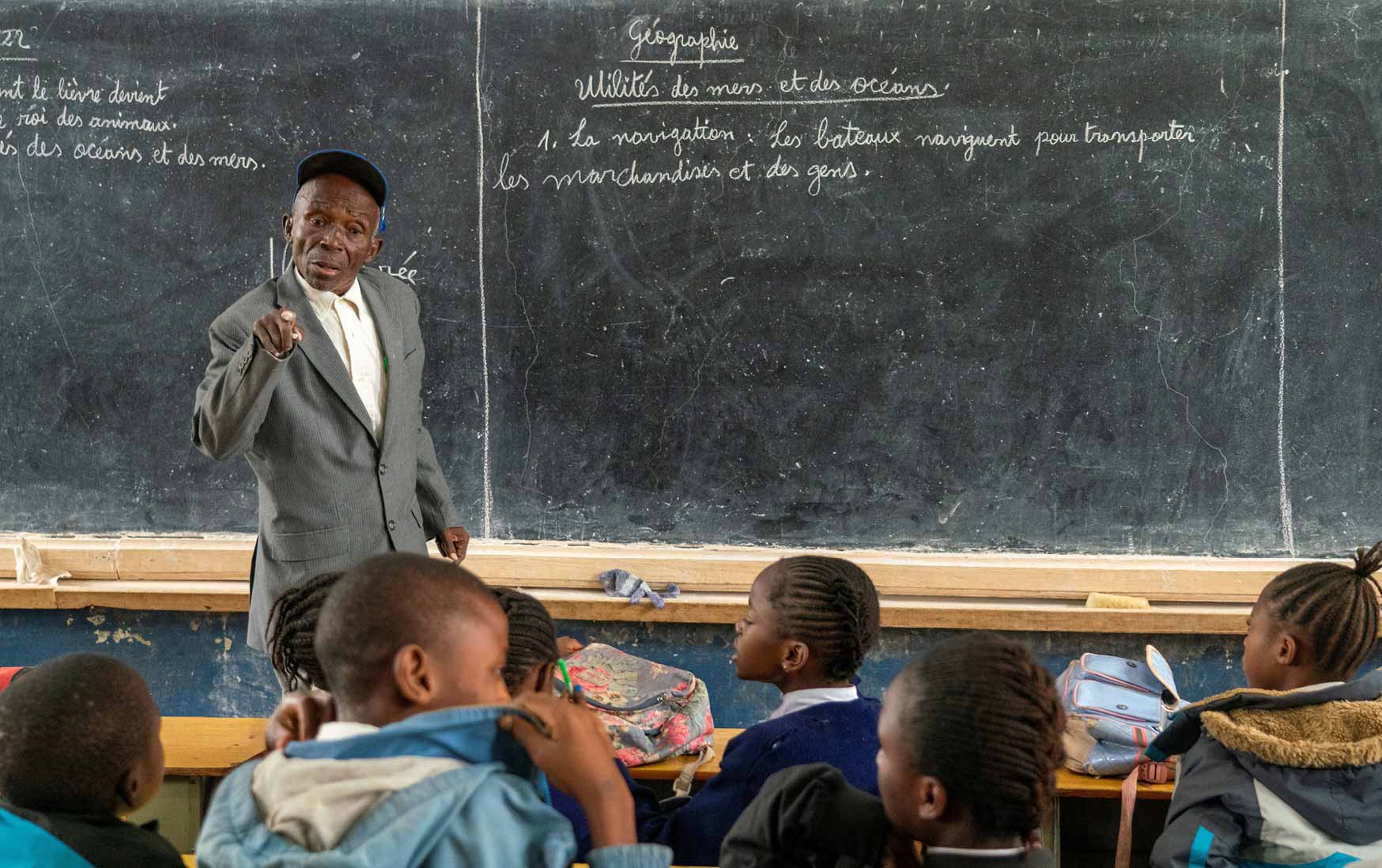

Bayard Kumwimba Dyuba, 84, a teacher since 1968 and who is awaiting retirement, teaches in his 5th year primary classroom at the Kiwele II primary application school in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2022. (Photo: Junior Kannah/AFP)

Recalibrating the “new” social contract between the state and its citizens and restoring public trust in government is therefore non-negotiable. With this in mind, and recognising that the state alone cannot solve the continent’s challenges, governments now need to consider smarter, more holistic, and scaleable solutions.

Here, governments should prioritise three key areas – transforming the culture around public service, leveraging the role of technology, and collaborating with the private sector.

As Ghanaian intellectual and entrepreneur Bright Simmons noted at the annual Warwick Africa Conference in February this year, a mindset shift is required to change the public service culture across Africa. Although the state typically is the largest employer in most African countries and pays relatively well, this is often not matched by the standards or technical ability required to deliver effective service delivery. To inculcate a new culture of excellence will therefore require a change in approach that draws on best practices from other parts of the world.

Using examples from France and Japan where civil servants are recruited through competitive exams, and Singapore where public sector pay is on par with that of the private sector (a legacy of the Lee Kuan Yew era), there is a deep and urgent need to foster a more meritocratic culture, aligned with positive incentives. This must be complemented by the infusion of young talent and innovation, necessary to disrupt slow and cumbersome bureaucracies across Africa’s public services. Moreover, Simmons argues that creating an ethos of pride and prestige within the public service is essential to attract the best and brightest minds and foster a culture of excellence – which could have a transformative impact on countries.

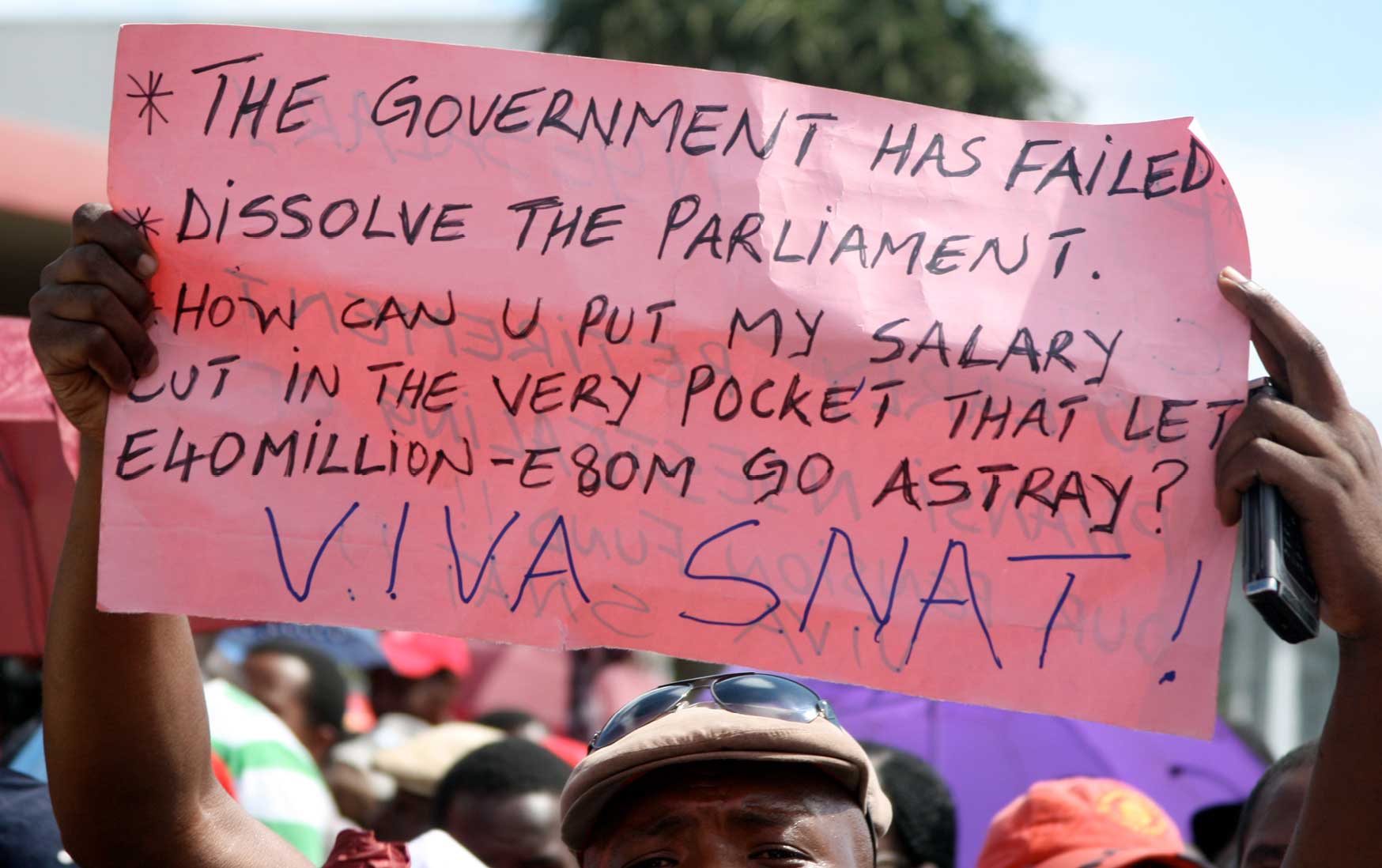

A Swazi public servant holds a placard as he takes part in a protest march gathering thousands in Mbabane in March 2011. (Photo: Jinty Jackson/AFP)

To this end, there are a number of powerful initiatives worth noting. Future Elect, led by Lindiwe Mazibuko, aims to support 1,000 public service fellows annually. The organisation delivers non-partisan leadership development and training programmes to young leaders in Africa to prepare them for leadership roles in politics and the public service. By engaging and training people to participate in the public life of their countries, Futurelect hopes to contribute to the revival of trust in politics and government and the strengthening of democracies in Africa. Similarly, in Nigeria, the #NotTooYoungToRun campaign, spearheaded by Samson Itodo, resulted in a constitutional amendment and a reduction in the age limit for public representatives in Nigeria.

The de-politicisation of public service is also imperative, argues Menzi Ndhlovu, a senior analyst at Signal Risk. For the continent to progress, “governments and bureaucracies can no longer be the grazing pits of ruling parties,” he adds.

Next, is the role of technology. There have been numerous examples across countries and continents where technology has been employed with great success to improve public sector efficiency. Through its e-Estonia initiative, Estonia has built a digital society and developed the most technologically advanced government in the world. Practically every government service is paperless and performed electronically. In one of its flagship initiatives in 2000, the government decided to introduce electronic identity cards, which allowed citizens to identify themselves digitally and sign documents or actions online. Using eID, citizens can review their personal health records, submit their tax declarations, and vote in elections online. This has reduced the administrative burden for both the state and citizens during public service delivery, saving them approximately 820 years of working time every year. And according to the Estonian government, the reduced working time corresponds to fiscal savings of around 2% of Estonia’s GDP annually in salaries and expenses.

A Ghana government promotion for its online passport application system.

This digital connection between the citizen and the state stands in stark contrast to “traditional public administration” and has dramatically improved trust and confidence levels in government. In keeping with this trend, Taiwan has leveraged the internet as a space for civic participation, dialogue, and consensus building. The idea, according to Minister for Digital Affairs Audrey Tang, is to “Imagine a digital technology that improves democratic discourse, instead of destabilising it. Imagine a form of algorithmic design which yields consensus rather than cleavages.”

In an African context, there are few success stories, but Ghana stands out. Beginning with the launch of online passport renewals in December 2016 and a paperless port system in September 2017, the authorities have created digital platforms for a range of government entities, including the Lands Commission, the Ministry of Tourism, and the court system. These efforts have paid dividends for the economy, via improved efficiency and transparency of administrative procedures. Such changes have seen a rise in import revenues, according to the Ghana Revenue Authority – mainly attributable to the digitisation of permits and fee payments.

Innovation has also been implemented in the healthcare sector, with the launch of a new platform in December 2018 to enable online renewals of the National Health Insurance scheme card via mobile phone. These moves have been supported by high and rising internet access, with the smartphone penetration rate standing at around 80%. Indeed, digital technology was central to Ghana’s successful Covid-19 response. Moreover, such endeavours have helped manage corruption while significantly improving the knowledge and skills of public servants. And far from being a threat to jobs, technology is likely to transform them. Indeed, it is far more likely to play an enabling role and create opportunities for prosperity, skills and knowledge transfer and industrialisation.

Importantly, many of these digital initiatives are public-private partnerships between Ghana’s government and tech companies and they are now changing the way citizens interact with their government. Combining private sector efficiency, competition and know-how with government legitimacy, scale and convening power, offers a template for policymakers across the continent to co-create the future of delivery.

A dermatologist at Rabito Clinic in Accra takes care of a patient in her consulting room in July 2018. (Photo: Cristina Aldehuela/AFP)

However, the private sector alone is not a silver bullet and should be viewed as a partner with a specific role rather than a substitute. Indeed, the deficiencies of winner-takes-all capitalism, solely based on profit motives rather than overriding considerations for the public good, have been exposed. Indeed, unchecked private sector involvement can have devastating consequences, as outlined by Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington.

In their recent book, The Big Con, they highlight the dangerous consequences of outsourcing state capacity to the consulting industry. The book demonstrates how an over-reliance on companies such as McKinsey & Company, Boston Consulting Group, Bain & Company, Price Waterhouse Coopers, Deloitte, KPMG, and Ernst & Young “stunts innovation, obfuscates corporate and political accountability”. They argue that consultancies have repeatedly weakened businesses and hollowed out state capacity. The South African case, where McKinsey and Bain were embroiled in scandals with state enterprises, is a prime example of such unsavoury behaviour.

“The more governments and businesses outsource,” according to Mazzucato and Collington, “the less they know how to do.” The need for clear guardrails to protect against exploitative practices and perverse incentives is apparent, while emphasising the leading role of a capable and caring state at the centre of the development process.

Looking ahead, there is some optimism. Post-pandemic, a more harmonious relationship between government and private enterprise has begun to take root across many parts of the continent. For example, governments in South Africa and Rwanda were able to convene private and third-sector actors to fill gaps in funding, skills, expertise, and networks, with positive results. Similarly in Nigeria, private sector players came together to form the Coalition Against COVID-19 (CACOVID), which provided financing for the immediate purchase of medical supplies and the creation of isolation centres.

The shift to a more collaborative approach can yield significant benefits. First, it could result in a shift in focus for companies from shareholder value to stakeholder value – an area of particular importance considering Africa’s huge inequality gap. A more caring form of capitalism, which prioritises people over profits, could yet emerge in the aftermath of the pandemic as companies adjust their business models for relevance. Second, by viewing business as a strategic partner rather than an enemy, material improvement in the business environment and investment climate could be awakened, as governments become more engaged and responsive to the private sector’s needs.

However, any comprehensive long-term solution requires solving the ongoing trust deficit between the state and its citizens, whose expectations and realities are wildly divergent. The associated paradoxes in this dilemma – namely the short-term thinking of governments with long-term needs of their populations, their limited fiscal room but excessive spending on consultants, as well as their archaic bureaucratic structures juxtaposed against the youthful energy and technological innovation of their populations – will not be easy to resolve.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[