The world is entering a new era of great power competition. Renewed, and emerging rivalries between major countries including China, India, Russia and the United States will define how the world navigates some of the great challenges of this century: conflict, technological disruption, climate change mitigation and poverty alleviation.

A “great power” is a country which is able to exert its influence in economic, military and political terms, in a manner which extends well beyond its own geographic region.

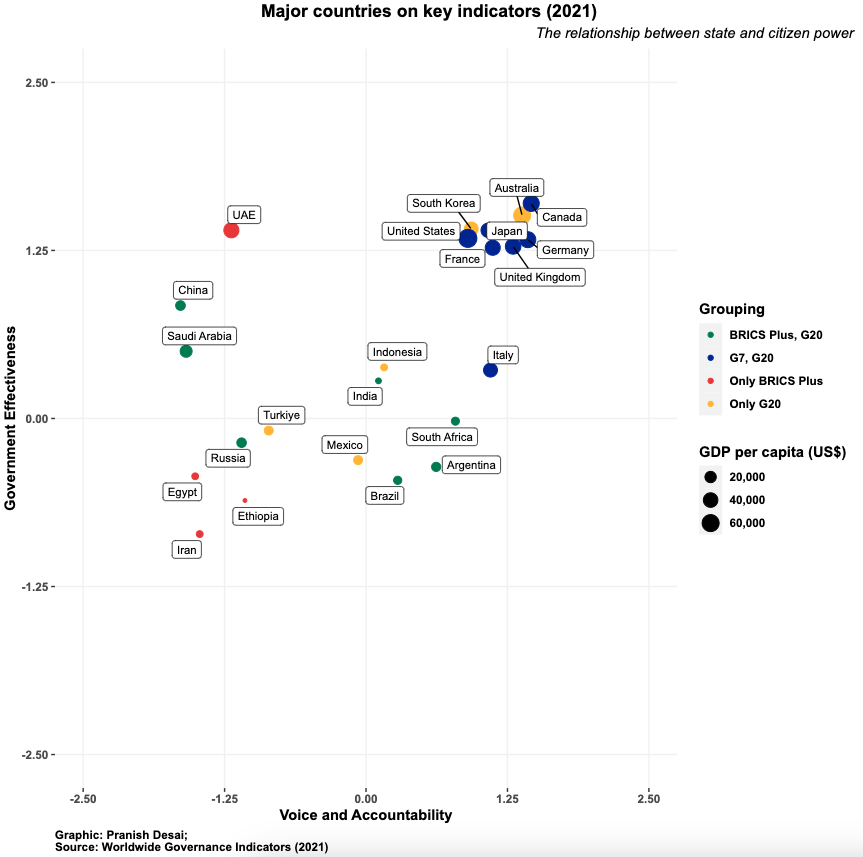

Concerns about how resurgent competition between these nations will affect other nations and the international system have become prevalent in the wake of several recent high-profile summits, including the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, and the G20 summit in New Delhi.

The last significant era of great power competition, the Cold War, offers a useful illustration of both the benefits and the costs of such a period. The Cold War was an era of substantial technological innovation and economic growth. While it is difficult to attribute all of this to the Cold War, there is no doubt that the competition between the US and the USSR helped spur humanity to cross new frontiers in space, medical technology and industry.

On the other hand, the ideological, and proxy-based nature of the competition between the US and the USSR meant that many immoral regimes played up their anti-capitalist or anti-communist credentials to receive great power support. At the same time, the superpowers often preyed on weaker regimes to advance their own foreign policy objectives.

Apartheid South Africa’s active militarism toward perceived “communistic threats”, whether those “threats” emerged from inside or outside of its borders was a classic example of an illegitimate regime exploiting these Cold War dynamics.

Major Western powers, most notably the US and the UK were often reluctant to directly sanction the Apartheid government while the Cold War was ongoing, despite some moral qualms about the system of racial segregation. It was telling that these powers became much more openly forceful in pushing for negotiations to end Apartheid once the Cold War itself was ending.

Today, South Africa remains important to the great powers. In fact, according to United Nations trade data, it is the largest individual trading partner which China, the EU, India and the US each have on the African continent. It also ranks among the top five African countries in terms of aggregate trade with Russia. This is a notable statistic considering Africa is home to many of the youngest, and fastest-growing populations on earth.

Precisely because of these factors great powers will try to lobby for South African support, especially over contentious issues where the great powers are in dispute. Even as a democratic nation which tries to pursue a policy of “non-alignment” over these rivalries, South Africa will never be fully insulated from great power pressure. This is especially so if one of the great powers fears that South Africa is no longer “non-aligned”.

One recent episode demonstrates this point well. In May 2023, the US ambassador to South Africa, Reuben Brigety alleged that South Africa had supplied arms to Russia in December 2022, using the Russian carrier Lady R. To date, Ambassador Brigety has yet to offer tangible evidence to validate these claims.

The subsequent executive summary from the investigative panel report President Ramaphosa commissioned to investigate the matter indicated that “despite some rumours that equipment or arms were loaded on the Lady R, the Panel found no evidence to substantiate those claims.”

Ambassador Brigety’s allegation followed months of simmering tensions between the US and South Africa. Prior to the Lady R allegations, US-SA tensions peaked in the aftermath of South Africa’s decision to partake in planned naval training exercises with Russia and China in February 2023.

Considered in the broader context of Russia’s active war in Ukraine, the largest “flashpoint” in today’s era of great power competition, proceeding with these exercises was harmful to South Africa’s image as a non-aligned country. Restoring South African credibility after the naval exercises, and following Ambassador Brigety’s allegations, required months of careful diplomacy.

The cornerstone of that approach was the successful attempt to convince Russian President Vladimir Putin to eschew in-person attendance at the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg.

For many, these events have exposed a contradiction in South Africa’s foreign policy. In particular, many see the strategy of non-alignment as incongruent with our constitutional aspirations for “human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.”

However, as history shows, in an era of great power competition, a clearly articulated position of non-alignment is the most prudent way for South Africa to preserve its own sovereign integrity while projecting its human-centred values at home and abroad.

Although the practice of avoiding any direct or proxy stances during a time of great power competition long precedes the Cold War, the specific strategy of non-alignment arose during the Cold War itself. Especially in the immediate aftermath of World War II, many developing countries had a material reason to avoid being drawn into the US-USSR rivalry, which could easily have turned into a “hot war”, over several flashpoints in the Korean Peninsula, Central Europe and the Caribbean.

Today’s nascent era of great power competition is no different, with existent or emerging flashpoints in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, the Pacific Ocean and the Indian subcontinent. Specifically aligning with one great power or another does not serve South Africa’s developmental goals, or its ability to promote human rights more broadly.

South Africa’s interests are best served by maintaining generally effective relationships with all the great powers, even when there are specific areas of disagreement. The relationship which existed between the Mbeki and Bush Administrations during the 2000s is a good example of this principle in action.

Significant differences existed between the two governments over contentious issues like the Iraq War and the HIV/Aids epidemic. Yet, through proactively maintaining dialogue, and promoting high-level engagement in both bilateral and multilateral forums, there was significant room for cooperation over critical security and humanitarian issues. At the time, this was especially important for South African interests because the US was then the world’s only true superpower.

As we see in examples like the US invasion of Iraq, South Africa’s early response to HIV/Aids, and Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, there is often a strong overlap between policy failure and moral failure. In any era, a democratic South Africa must be willing to condemn these failures privately and publicly even if they are committed by the most powerful nations.

In making such condemnations, South Africa must also be clear that our disapproval of a specific act does not mean that we are now automatically a part of one global power bloc or another. Throughout modern history, the most effective nations have been able to acknowledge disagreements, without allowing those disagreements to prevent cooperation in other, equally important areas.

By proactively maintaining the synergy between non-alignment and human-centred values, and clearly articulating this position, South Africa will give itself the best chance of reducing the risks posed by great power competition, while reaping the benefits. Following such a strategy, it can also be an example for other developing nations on how they too can navigate this era of uncertainty.

Pranish Desai is a doctoral student in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His core areas of focus are in comparative politics and political methodology, with a specific interest in the politics of Southern Africa. Between 2021 and 2024, Pranish held several key positions within the Governance Insights and Analytics programme at GGA. In these roles, he was centrally responsible for the elevation and enhancement of the Governance Performance Index as GGA's flagship governance assessment tool. Before departing GGA, Pranish also played a key role in the development of our strategic framework for the 2024-2028 period.