Media Release

Ugandan musician turned politician Robert Kyagulanyi, also known as Bobi Wine, lays flowers during a prayer for the victims of the protest against his arrest at the headquarters of his opposition party, the National Unity Platform (NUP), in Kampala, Uganda, on November 21, 2020. – A Ugandan court on November 20 charged opposition leader Bobi Wine over an election rally which allegedly flouted Covid-19 rules, then freed him on bail, after his detention sparked violence that left 37 dead. Photo: AFP

Our continent has had its share of despots in the post-colonial era. There was a time when it looked like they were on their way out. Sadly, for the citizens of Uganda and a handful of other African countries, despotism is again on the ascendancy. Despotism and autocratic consolidation invariably destroy good governance. At Good Governance Africa, we contend that this governance deficit not only leads to reckless (if calculated) brutality, but ultimately to insecurity for the despot himself.

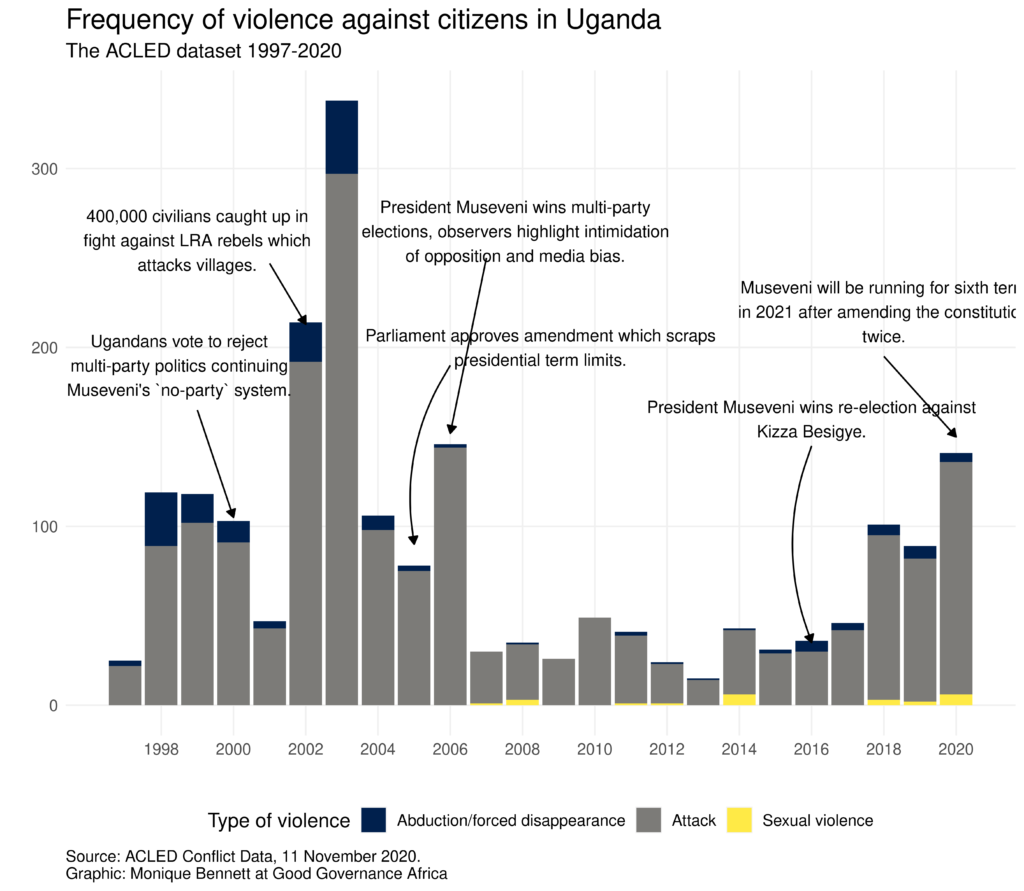

Harrowing scenes from Uganda shared across social media platforms show the human carnage behind the bland statistics that at least 28 people have been killed and 557 arrested, with scores more beaten, shot or maimed in protest action against the state over the weekend. Uganda goes to the polls in 2021. As the graph below clearly demonstrates, history is simply repeating itself. The cycle of electoral violence is mirroring, almost to a tee, the 2005 eradication of presidential term limits followed by extensive intimidation and repression of any form of opposition or protest in 2006. The 2016 elections were relatively peaceful by contrast.

Museveni came to power in 1987 and is fast approaching the record for the longest-standing autocrat on the continent. Like Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, and Jose Eduardo Dos Santos of Angola, who ruled for 37 and 38 years respectively, Museveni has followed the careful script of eradicating internal opposition to his rule. External opposition has been a mere irritation in Museveni’s political calculus. At every opportunity, he has accumulated more power to himself and, in the process, minimised the probability of an internal coup being launched.

Each power-grab eroded the integrity of the internal power-sharing mechanism, reducing the probability that remaining members of the ruling coalition would band together and oust him from office. With increased personal access to power and rents, Museveni could calculate just how large he required his patronage network to be to avoid disrupting the equilibrium. The prospect of impending oil wealth simply deepens this scourge and intensifies the probability of ‘successful’ autocratic consolidation.

Given this analysis, why do we contend that the resultant governance deficit is ultimately risky for the apparently ‘successful’ autocrat? Because Mugabe and dos Santos were both removed from their perch by bloodless coups launched by their own ruling coalitions, a relatively novel occurrence in our more recent context. Moreover, even though the Arab Spring did not produce lasting governance gains, autocrats do risk widespread popular grievance against their rule. This risk is increasingly concomitant with a rising risk of organised crime and terrorism proliferation.

Extremist insurgents take advantage of local grievances. Local grievances are almost always a direct function of poor governance. In the absence of governance, public goods cannot be delivered, and broad-based economic growth cannot occur. In resource-wealthy contexts, unscrupulous extractive industry companies are often willing to pay short-term rents to politically connected gatekeepers to gain access to the relevant resource. This exacerbates local grievances. This matching of short-term politics and short-term business thinking is an explosive cocktail that destroys the long-term prospects for both.

Museveni will rue the day he neglected good governance (even before he destroyed presidential term limits) when terrorists start blowing up Uganda’s oil fields. That oil companies off the coast of Mozambique have started to employ private military companies to prevent terror attacks is just one example of the growing trend. Only a few weeks ago, the Islamic State Central Africa Province, mounted an attack on Mtwara in southern Tanzania.

The best empirical evidence we have about the resource curse shows that natural resource wealth correlates with under-development in the absence of institutions that ensure good governance. What we don’t have evidence for yet, but that we strongly predict on the basis of the trends unfolding, is that the resource curse will no longer benefit elite insiders at the expense of the majority (the traditional resource curse), but instead destroy the prospects for the very autocrat who destroyed those governance institutions.

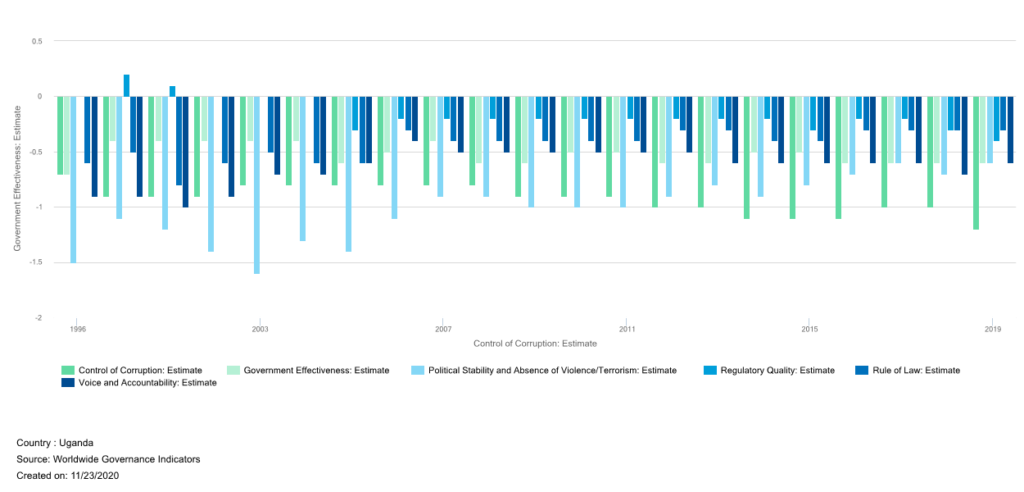

In Uganda alone, the governance deficit is clearly on display in the graph below. The country has not scored above 0 (where -2.5 is the worst possible estimate and 2.5 the best) since 1995, according to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators.

According to the Fragile States Index (powered by The Fund for Peace), Uganda has seen a near continuous improvement since its 2016 low (but with a preceding average deterioration from 2006 to 2016). In this instance, the past decade is a poor predictor of the future.

On the Political Indicator Trends, similarly, the apparent improvement of public service delivery is undermined by a poor human rights record and a poor state legitimacy score. The country’s failure to improve its governance scores, combined with Museveni’s iron grip on power, has not only led to despair for millions of citizens but will increase the fragility of Museveni’s own position within his ruling coalition. Junior members of the coalition, with longer time horizons (and therefore lower discount rates) will possess increasingly stronger incentives to overcome their collective action problem and overthrow the ruler.

This is especially likely to be the case if the risk of extremist activity proliferates. Given the current expression of citizen grievance, and brutal state response, over poor governance, this risk is evidently growing.

The bottom line is that abrogating good governance, while apparently a useful short-term bet for personal power acquisition, is likely to lead to longer-term insecurity for the autocrat. This is a lesson that all leaders across the continent should heed. It should also lead to stronger condemnation and action from regional bodies that seem impotently intent on allowing the status quo to continue ad nauseum.