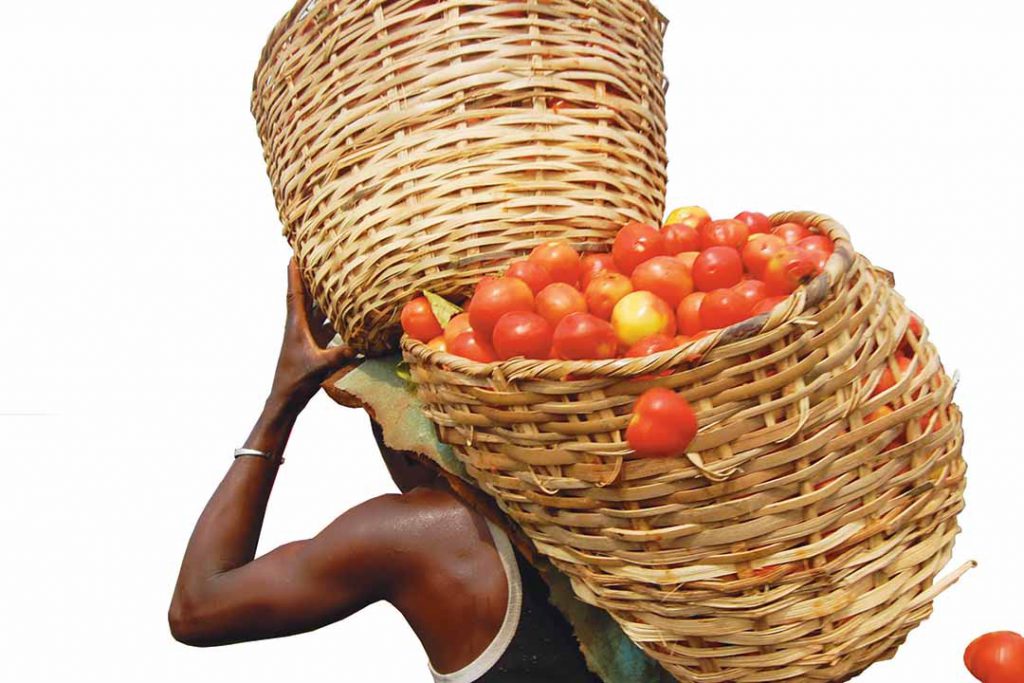

For the most part, urban farming in African cities is a livelihood strategy without official sanction or acknowledgement

According to the UN Population Division, the proportion of Africans living in urban centres will rise from a little over 40% at present to more than half the continental population by 2050. Africa’s future will increasingly depend on its cities and their capacity to accommodate more people.

An important element in all this will be ensuring an adequate and affordable food supply. This is not merely a matter of adequate nutrition. The food supply to cities is directly linked to the stability, and viability, of Africa’s urban polities. A lack of access to food has historically been associated with politically charged violence. Indeed, “food riots” erupted in Africa on the back of rising food prices between 2007 and 2010 – and more recently in Sudan at the beginning of this year.

One solution that has attracted interest is urban agriculture – cultivating crops or livestock within or on the fringes of cities. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FOA), around 800 million people around the globe are engaged in some form of urban farming. The FOA estimates that just one square metre of urban ground can produce as much as 20 kg of foodstuffs in a year.

Urban agriculture has long been a part of the African urban economy – typically, as part of the continent’s informal economy. Studies have shown that large numbers of urban households, probably over a third, are engaged in some form of agriculture. And depending on the city and the crop concerned, urban farming can supply up to 90% (perhaps even more) of the consumption needs of a community. But for the most part, urban farming is a livelihood strategy without official sanction or acknowledgement.

In Africa, urban dwellers frequently retain a close link to their places of origin and the skills associated with their rural homestead. But, interestingly, urban farming is more commonly practised by middle-income people with backyards rather than the poor, according to Diana Lee-Smith of the Mazingira Institute, a development-oriented civil society body based in Nairobi. The poor live mostly in dense slums where farming isn’t easy. About two thirds of Africans who farm in cities see it mostly as a source of food. “Urban dwellers who farm are both better nourished and better off financially,” she told Africa in Fact. “Urban farmers have consistently above-average incomes.”

The type of urban agriculture used in cities depends on the context and the land, water, and inputs such as fertiliser that are available. In Yaoundé, Cameroon, urban farmers use the wetlands within the city (the so-called bas fonds) to cultivate maize, vegetables and root crops such as cassava. In Kampala, Uganda, well-watered peri-urban areas offer opportunities for cultivation on a relatively large scale, while those nearer the centre of the city are limited to small garden-style plots. Some urban farmers use unoccupied spaces for cultivation, alongside roadways for example.

Urban agriculture sometimes relies on the wastes produced by the surrounding community, such as waste water for irrigation and organic solid waste for fertiliser. In some instances, inputs are sourced from both rural and urban centres, according to a 2010 study of African urban agriculture produced by the Canada-based International Development Research Centre and the Peru-based International Potato Centre. “In Nairobi, market gardeners in urban and peri-urban areas access compost produced from domestic organic wastes by urban recyclers and manure from Maasai cattle herders in Nairobi’s rural hinterland. In Nakuru, Kenya, livestock keepers use the manure from urban-raised livestock to fertilise crops on both urban and rural plots.”

As awareness of the cumulative scale and importance of urban cultivation has grown in recent decades, policymakers and development activists have investigated how it can be integrated into cities’ developmental efforts. Addis Ababa, Cape Town, Kampala and Nairobi have units within their administrations to promote it.

According to a study by the International Network of Resource Centres on Urban Agriculture and Food Security, urban agriculture benefits mainly less-affluent households. Among other things, it generates employment, reduces food expenditure, and provides income from the sale of produce. Knock-on benefits include opportunities for food processing, the sale of inputs such as feed and pesticides, and services such as transport. In addition, research in Kampala, Uganda, found that it had positive nutritional outcomes among children in families engaged in urban farming. Indeed, after the post-election violence in Kenya in 2009 market gardens in Nairobi were instrumental in maintaining the city’s food supply as other channels were disrupted.

Modern technology is also bringing increasing sophistication to urban agriculture, making it possible to expand production and creating openings for agricultural entrepreneurs. Vertical cultivation (growing crops in structures composed of ascending layers), hydroponic cultivation and greenhouses all produce crops more intensively while using limited space.

“You can see rooftop gardens and sack gardens in slums or on top of low-income highrise flats,” says Lee-Smith. “You can also see high-value greenhouse investments around cities to access the market demand.” As Africa’s growing middle-class increases, innovative and technology-dependent production systems are servicing an ever-growing market, she adds.

Environmental sustainability is a key driver of urban agriculture, according to Kyra Rautenbach, a Pretoria-based, sustainable-design specialist with the international Aurecon Group. “Urban agriculture is changing in Africa, and it is no longer an activity associated only with the urban poor,” she told Africa in Fact.

The rise of sustainability rating tools has increased consumer interest in the availability of fresh food and in urban farming. For example, the South African Green Star Sustainable Precincts Rating tool recognises buildings that provide access to fresh food through the use of community gardens or productive landscapes. In a new trend, commercial office spaces could be integrated with urban farming facilities, allowing staff to participate in maintaining and harvesting the produce.

Markets for urban agricultural produce are largest in cities. Combined with growing demand for “organic” food, urban farmers have a ready market to exploit, Jju Mba of Camp Green Uganda, an NGO, told Africa in Fact.

But urban agriculture can face difficulties. Produce cultivated in the conventional “low-tech” mode is vulnerable to contamination through soil or water that contains lead, arsenic or pathogens. Also, poorly managed run-off from urban farming plots can pollute water sources used by city populations. The FOA has warned of “unsustainable intensification”, and the dangers posed by the overuse of pesticides and polluted water.

Administrative environments can be equally constrictive: archaic regulations may serve to restrict the spaces available for cultivation, and the lacunae in property rights (a widespread lack of land title, for example) can render urban farmers vulnerable to eviction and seizure. Urban development in Africa’s cities is also shrinking the acreage available for urban farming. “Urban real estate developments are reducing space for farming,” says Mba. Public spaces scheduled for development such as golf courses and leisure parks could be converted into community gardens, he argues. Meanwhile, Africa’s urban poor continue to suffer from insufficient nutritional intake, suggesting that the urban agricultural system has not overcome a fundamental problem contributing to African food insecurity: food costs. University of Cape Town researchers Gareth Haysom and Jane Battersby argued in a 2016 contribution to The Conversation, a website specialising in debate among academics, that urban agriculture was not a solution to food insecurity because it cannot address the fundamental problems in economic realities, such as inequality.

But urban agriculture can be an effective complement to conventional, rural cultivation. New production techniques, coupled with shifting demands, are increasing its value-add potential. They hold out the possibility that urban agriculture can be integrated into value chains, at which point it becomes economically significant. When urban agriculture is seen as a viable form of employment, it also helps to tackle unemployment, which is high in African cities, says Mba.

To further enable this, regulatory environments that present unreasonable restrictions on urban farming will need to be reviewed. In particular, security of tenure is critical if urban farmers are to invest resources in productivity-enhancing technologies.

Urban agriculture is not yet a major contributor to urban economies, but it is growing in significance and offers considerable growth potential, says John Purchase, head of South Africa’s Agricultural Business Chamber. “New technologies and production techniques through hydroponics and vertical agriculture provide opportunities for large-scale competitive production in a limited environment,” he told Africa in Fact.

Terence Corrigan is an independent researcher, political consultant, writer, editor and illustrator. He is currently a research fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) in its Governance and African Peer Review Mechanism Programme and a policy fellow at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR).