Human rights violations exacerbate the displacement of northern Mozambicans, already facing crisis levels of food insecurity

“There is no greater sorrow on earth than the loss of one’s native land” – Euripides, 431 BC

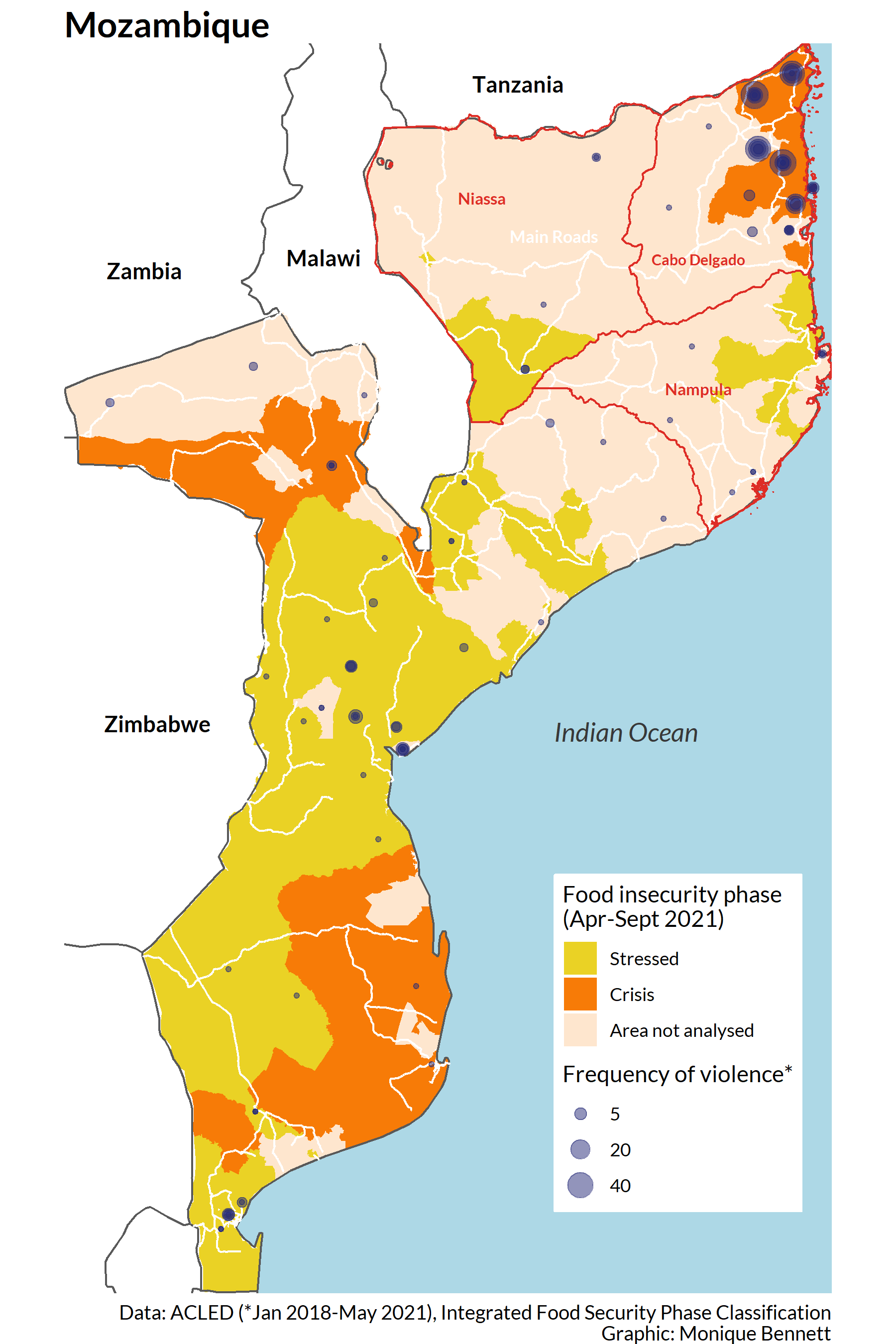

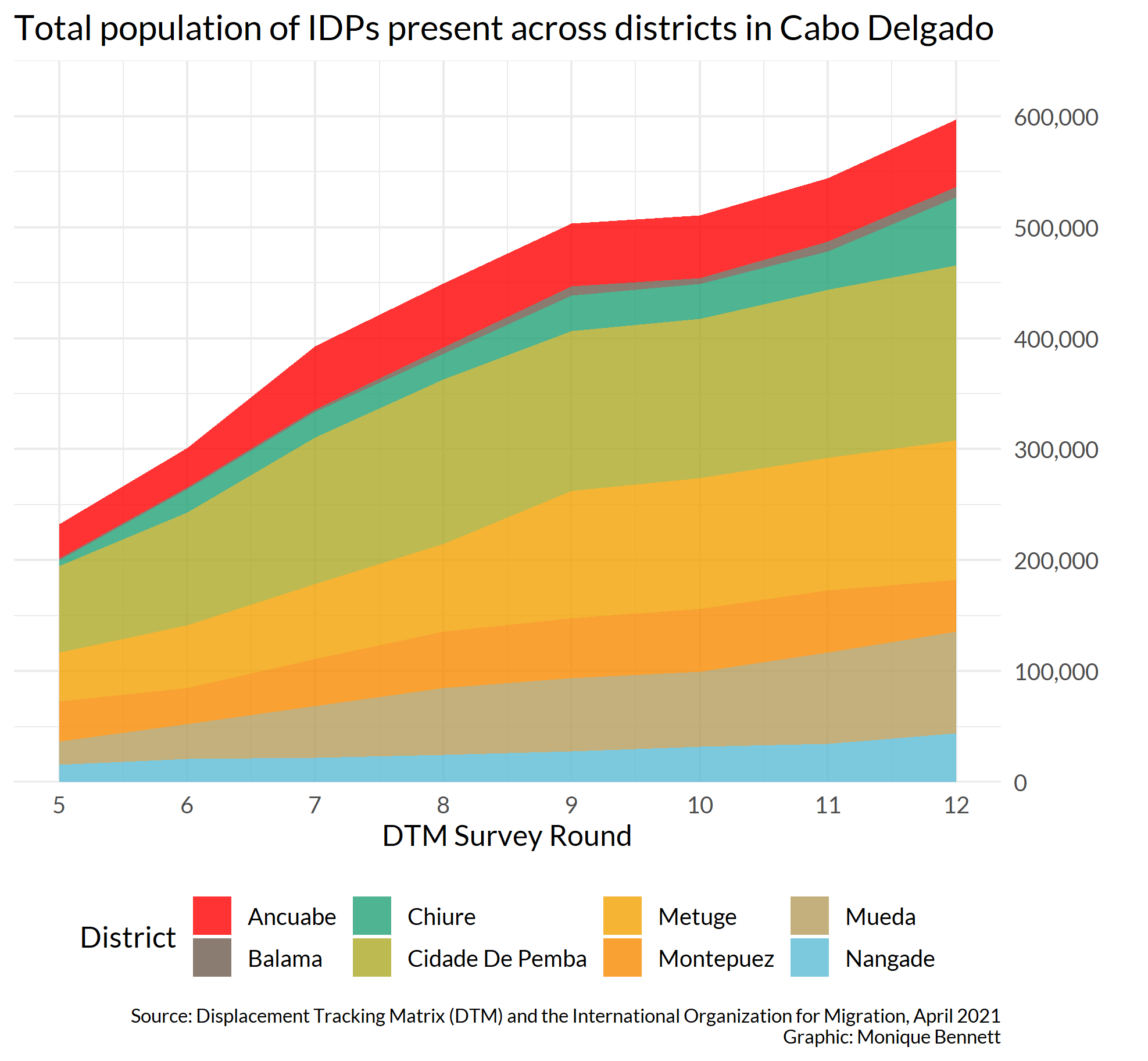

The United Nations (UN) estimates the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to insecurity in Cabo Delgado since 2017 at 697,538: roughly 30 percent of the province’s total population. There is a general trend of displacement towards district capitals, and southwards. Some continue to head north, though, attempting to cross the border into southern Tanzania. Many arrive at their destinations traumatised, separated from their families, with just the clothes on their backs. Having travelled long distances by land or boat, they are often in desperate need of medical attention. However, hunger is the most pressing concern for those displaced. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) categorises most of the northern region as “stressed”, and eight out of Cabo Delgado’s 17 districts are classified as facing “crisis” levels of food insecurity.

An aerial view taken on February 24, 2021 shows temporary houses in the Napala Agrarian Center of Metuge District, Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique. Photo: Alfredo Zuniga/AFP

Apart from the urgent humanitarian requirements, displacement has significant security implications. It can lead to a rise in inter-and intra-community violence, sexual exploitation, human trafficking, and other forms of crime. Affected people might resort to negative coping strategies such as prostitution, forced marriage, and recruitment into armed groups. Recent reports indicate, for instance, that the Islamist insurgent group, Ahlu Sunnah wa Jama (ASWJ), has been recorded directly targeting IDPs for exploitation and recruitment.

This negative feedback loop, created by the interdependence of humanitarian and security issues, can be seen in places like the Sahel. Fragility, migration, and violent extremism have been mutually reinforcing for decades, with devastating effects on the local population.

In line with the UN High Commission on Refugees’ (UNHCR) guiding principles, a “durable solution” to internal displacement might be considered achieved when IDPs no longer have any specific assistance and protection needs that are directly linked to their displacement, and can enjoy their human rights without discrimination on account of their displacement.

This is usually achieved through sustainable integration:

- back to their place of origin (return);

- in the area where IDPs have taken refuge (local integration); or,

- elsewhere in the country (relocation).

The Mozambican government’s slow response, continued lack of critical support to IDPs, and reluctance to work openly and transparently with regional and international actors on humanitarian aid efforts, means durable solutions to the IDP problem are far from being achieved, and the potential for a large-scale famine continues to increase.

Creating these solutions in line with best practices should not only be viewed as a responsibility to alleviate the suffering of the displaced. They are crucial to strengthening the resilience capacity of IDPs, interrupting the negative feedback loop generated by the interdependence of humanitarian and security issues, and are therefore a crucial part of a wider conflict resolution strategy for northern Mozambique.

The scale of the displacement and conflict-induced famine

As of March 2021, an estimated 630,241 IDPs were identified in Cabo Delgado, while an additional 64,919 were counted in Nampula, 1,153 in Zambezia, 1,072 in Niassa, and 153 in Sofala provinces. The majority are residing with relatives (80%), followed by formal/informal sites (13%), makeshift shelters (4%), and partially destroyed houses (3%). Children represent 46 percent of the IDP population, followed by women (31%), and men (23%). At least half of those displaced have been so two or more times since 2017.

Cabo Delgado is the least developed and poorest province in Mozambique. Communities were already experiencing various forms of deprivation before facing the compounding triple threat of climate change-related disasters in the form of Cyclone Idai and Kenneth, the COVID-19 pandemic, and an escalating armed conflict – all within a three-year period.

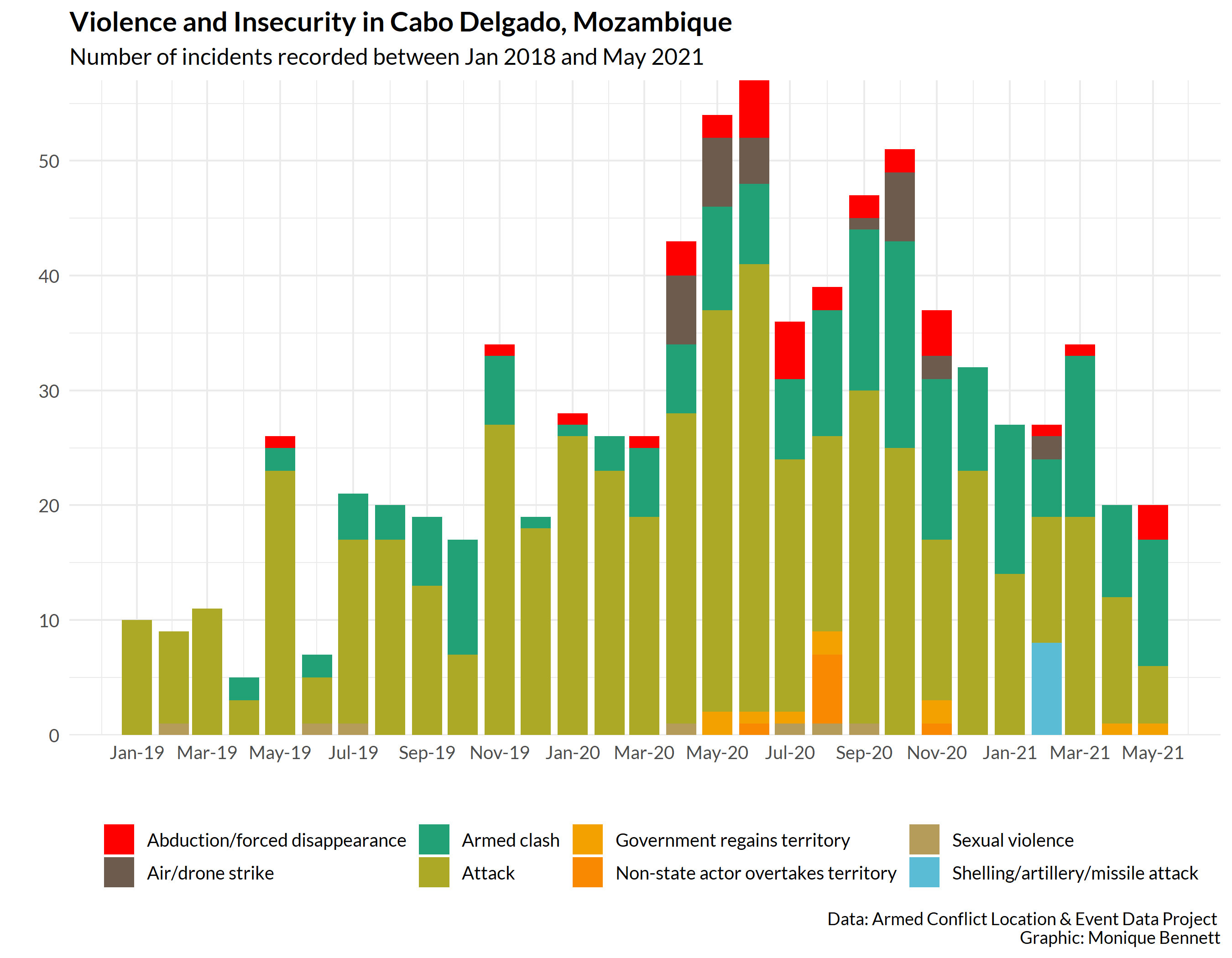

The high number of IDPs (697,538) relative to the comparatively lower number of citizens killed in fighting since 2017 (2,838) also speaks to the sheer horror of ASWJ attacks, which have included mass beheadings and dismembering, abductions of women and girls, and entire villages razed.

Displacement seems likely to also be driven in part by communities’ lack of trust in the security force’s ability to protect them from future attacks, or fear of themselves being the target of counterinsurgency efforts. As the ICRC has noted, gross violation of human rights against civilian populations can impact the duration, scale, and type of displacement. Extreme acts of violence, like those seen in Cabo Delgado, can generate preemptive displacement and impact the potential willingness of civilians to return.

In combination with Cyclone Kenneth in 2019, the conflict has disrupted agricultural and fishing activities across the region, food supply chains, access to basic services, and led to large-scale loss of livelihoods for the displaced and host communities across Cabo Delgado, Niassa, and Nampula. An analysis by Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) projects that 950,000 people are expected to face severe hunger in Cabo Delgado, Niassa and Nampula from now until September 2021. The World Food Programme (WFP) recently found that 50% of displaced children faced chronic malnutrition, and 21% of those under 5-years-old are underweight.

Government responses

Despite repeated attacks on communities by ASWJ since October 2017, reports suggest Mozambican authorities continued to encourage people to stay or return to their villages, underplayed the nature of the threat, and broke promises to dispatch military units to protect the most vulnerable communities.

These decisions delayed efforts to mobilise international aid and develop accommodation centres and other support structures for IDPs. This has resulted in around 80 percent of IDPs now residing with host families, many of whom are already living in poverty. Only in the latter half of 2020 did the State Secretariat begin identifying space in districts not affected by armed attacks, and parcelled out plots of land measuring 15 x 20 meters to displaced households.

By the end of February 2021, 21 of these resettlement villages had been created, but beyond demarcating plots and opening water sources, the government has not made available any other financial or material support to households who largely rely on international aid agencies for basic provisions. Interviews with resettlement village residents suggest there was very little consultation prior to the opening of these camps.

The Mozambican authorities have also been criticised by the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD), a local research institute, for prioritising the safety of on-shore liquid natural gas (LNG) facilities over communities, and not providing transport and safe passage to those fleeing conflict areas. Consequently, IDPs must often navigate long and perilous routes to safety, by land or sea. In November 2020, a fishing boat ferrying people fleeing to Pemba sank, killing dozens, and there have also been several reports of women and children being abducted in transit.

In addition to the access challenges created by continued insecurity, international humanitarian agencies have faced administrative hurdles created by the government. In May, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) stated that: “Significant restrictions are placed on the scale-up of the humanitarian response due to the ongoing insecurity, and the bureaucratic hurdles impeding the importation of certain supplies and the issuing of visas for additional humanitarian workers.” At least 57 UN staff have been awaiting visa approvals for several months and the International Organization on Migration (IOM) has called for greater access to be granted to humanitarian workers.

Between 15 and 22 April 2021, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) deployed a team to Mozambique, as part of a Technical Assessment Mission (TAM), to conduct an assessment and provide recommendations on the conflict in Cabo Delgado. The SADC team only spent one day in Cabo Delgado, and their movement in the province was restricted. The leaked SADC report recognised the scale of the displacement problem, and recommends that humanitarian assistance be rendered to IDPs as a matter of priority.

While President Nyusi has publicly voiced Mozambique’s willingness to work with the region and the international community to resolve the crisis in the north, in reality, his government tolerates as little outside intervention as necessary. This is ultimately to the detriment of communities in the north and prospects for building an effective regional strategy to resolve a regionalised conflict system.

IDPs and international humanitarian law

According to the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, IDPs are: “Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalised violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised state border.”

This is a descriptive definition and not a legal one, and while IDPs often share many of the same risks and deprivations faced by refugees, they are not afforded the same legal status and protections under international law. IDPs remain the responsibility of national authorities and are, in theory, entitled to the same rights and guarantees as any other citizen or habitual residents of a particular state.

In fragile or developing states like Mozambique, IDPs oftentimes find themselves in territories where the central government has either little capacity or interest in governing. They may also belong to an already marginalised ethnic group, or their displacement itself is the product of government abuses. In these situations, critical protection of IDPs falls to the international community, which must hope that the relevant state provides them with the requisite access and cooperation to effectively carry out humanitarian support work.

The Mozambican government continues to make it difficult for international humanitarian agencies to operative in Cabo Delgado, despite deepening conflict-induced food scarcity and widespread hunger. United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2417 was adopted in 2018 to draw attention to such situations. The Resolution underlines the importance of safe and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel to civilians in armed conflicts, and it also strongly condemns the unlawful denial of such access and depriving civilians of objects indispensable to their survival, including wilfully impeding relief supply and access for responses to conflict‑induced food insecurity. In extreme cases, the UNSC also has mechanisms for allowing humanitarian actors access without government consent, such as Resolution 2165, which gave allowed for the cross-border delivery of aid in Syria.

The way forward

In April, the World Bank approved the country’s eligibility to the Prevention and Resilience Allocation (PRA), unlocking up to $700 million in funding to prevent the further escalation of conflict and to build resilience in Mozambique, potentially signalling a shift in international donor attitudes towards the country. In parallel, the World Bank also approved a $100 million grant from the International Development Association (IDA) in support of the government’s Northern Crisis Recovery Project, which focuses on early recovery activities supporting IDPs and host communities in targeted areas. Since the 2016 hidden debt scandal, which saw international donors led by the IMF withdraw support to the Mozambique government, the northern provinces have been particularly impacted by the resulting economic fallout. Last year, Cabo Delgado’s provincial budget was reduced from 3.4 billion to 3 billion meticas, despite an increase in budgetary requirements to deal with the humanitarian crisis.

In April, Armando Panguene was removed as head of the Northern Integrated Development Agency (ADIN) and replaced with Armindo Ngunga, former secretary of state for Cabo Delgado. Created in early 2020 to drive development in northern Mozambique, ADIN has been criticised for its slow operational establishment, and the change in leadership could signal a new commitment to getting the agency operating more effectively.

To capitalise on these developments, creating durable solutions for IDPs and preventing conflict-induced famine should be centralised within the government’s strategy to resolve the conflict. In this regard the Mozambican authorities should:

- Provide greater support to provincial and local government in the north to deal with the enormous IDP challenge, and ensure funding reaches the district authorities most impacted by the crisis.

- Immediately remove barriers to access for frontline humanitarian agencies, such as impeding the importation of certain supplies and the issuing of visas for additional aid workers, and allow safe and unfettered access to provide food aid and medical care to civilians in need in Cabo Delgado.

- Deploy security services to provide safe passage to those fleeing conflict-affected areas, prioritise the protection of vulnerable IDPs, investigate and hold responsible those involved in cases of aid theft and abuse of women and children IDPs, and work with humanitarian agencies to facilitate improved access to high-risk areas.

- Empower IDPs to play a central role in finding durable solutions to their displacement through regular consultation and needs assessments.

To date, the UN’s $254 dollar call to fund its Humanitarian Response Plan (HPR) for Mozambique is only 2.6 percent funded. Concerted global action is required as a matter of urgency to address the IDP crisis and stop widespread famine, which together will almost certainly deepen the conflict.