Africa: an artificial patchwork?

Understanding the dynamics of ethnic conflicts in Africa means appreciating the role of ethnic identity

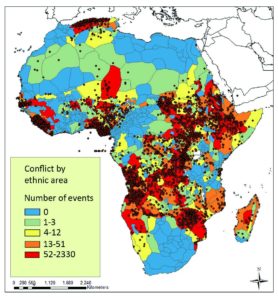

In 2011 Peter S. Larson, a professor at the University of Nagasaki, Japan, published an attempt to chart the interplay between ethnicity and African conflict. Larson used the 1959 map of 835 “ethnic regions” of Africa produced by anthropologist George Murdock. While admitting that Murdock’s map is “perhaps naïve”, Larson states that it remains an important source to Africanists. He then drew on the University of Sussex’s Armed Conflict and Event Location Database to plot current conflict events onto Murdock’s ethnographic map. Mapping conflict by national borders painted huge chunks of the African map red with danger, Larson found, but plotting the Sussex data onto the Murdock map altered the patterns. In particular, conflicts became identifiable as regional rather than as national or international. Moreover, he wrote, “one can see that conflict events largely occur within Murdock’s ethnic boundaries”. Yet he argued against the conclusion that African conflicts were mainly ethnicity-driven. As one example, Larson’s map revealed that the Algerian conflict is really a conflict between the government and the Amazigh, a Berber group of the Kabyle region of the Atlas Mountains who have a tradition of independence: Amazigh means “Free People”. By contrast, the map plots the ethnic element behind the secessionist war in Angola’s Cabinda enclave, where the Bakongo majority has developed a unique culture distinct from that of other Bakongo in the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Similar convergences of conflict and ethnicity can be seen in Ogoni and Ijaw militancy in the Niger Delta, the Tuareg insurrection of northern Mali, and other regions. Larson’s map was published just before the Arab Spring rolled out across the Maghreb. The latest Sussex map, published in 2015, shows the spread of conflict into Libya, especially to Benghazi.

Conflicts in Africa by ethnic region

Source: Peter S. Larson’s blog: https://peterslarson.com/2011/01/19/african-conflict-and-ethnic-distribution/

In Egypt it has moved into Sinai, where most people speak Bedawi Arabic, unlike Cairo’s Egyptian Arabic majority. In the former Somalia, conflict is centred in Mogadishu. Other conflicts are mapped in north-western Nigeria (Boko Haram), South Sudan, and the Central African Republic (CAR). The map shows that violence against civilians had declined in Zimbabwe, especially in Matabeleland. Meanwhile, civil protests continued in South Africa, as well as in many West African and Maghreb capitals after the lull following the Arab Spring. Perhaps more telling is Sussex’s 2015 map of the agents of violent conflict in Africa. Searching only for “communal militia” reveals a widespread tendency to armed communal violence, in distinct regions, that likely involves an element of ethnicity. For example, in Libya communal militia-driven conflict occurs in remote and coastal areas that are homogeneously Arab or Toubou. But the civil war is not only ethnicity-based; it is also a politico-confessional conflict between former Gaddafi supporters and Salafist and democratic forces.

Spread of main languages in Africa

Source: Peter S. Larson’s blog: https://peterslarson.com/2011/01/19/african-conflict-and-ethnic-distribution/

Militia conflict in south-central Nigeria occurs in the Christian Igbo heartland, far away from Boko Haram’s strongholds. The conflict on the CAR/Congo border is primarily confessional, between Muslim Séléka and Christian Anti-Balaka militia. The conflict in Darfur, in the Sudan, involves a number of ethnicities, as well as ethnicised environmental drivers. In South Kivu, in the DRC, the conflict involves several ethnicities, as well as ethnicised drivers deriving from the long aftermath of the Rwandan genocide—complicated by relations with endogenous political militia sometimes supported by foreign governments. Community conflict in highland Kenya is regional and ethnic, and relatively isolated from the multiculturalism of Nairobi. The emergence of communal militia in South Sudan is mostly a result of the breakdown of the Dinka-Nuer ethnic compact, but is also driven by the fragility of the new state and a tendency by all parties to resort to military “solutions”. Communal armed conflict in former Somalia involves a power struggle between six major Somali clans, plus Al-Shabaab, and only a smattering of “outsiders”. This brief overview is an indication of the difficulty of accurately charting the role of ethnic identity in African conflicts. Each involves many facets, including the influence of ethnicity, which is itself complicated by history. Even distinctly ethnic civil conflicts such as the 2007/08 pogroms in Kenya and the wave of violence in 2008 in South Africa involved a blend of other factors and influences. In Kenya, where perhaps 1,500 were killed and perhaps 600,000 displaced, the crisis was rooted in political unrest following the contested election of President Mwai Kibaki. Opposition supporters of his opponent, Raila Odinga, went on the warpath, killing members of Kibaki’s ethnic group, the Kikuyu. This ethnicised the conflict, with Kikuyu striking back at the Luo and Kalejin ethnic groups. In South Africa 62 people were killed and 100,000 displaced in violence supposedly directed only at foreigners. But the media’s “xenophobic” tag was inaccurate; only two thirds of those killed were foreigners, among them Somalis and Mozambicans. Resource contestation and business jealousy were the root causes, while the violence also had elements of sheer criminality and the settling of personal scores. This was also the case in Kenya where land, hunger, poverty and criminality skewed ethnic tensions. More coherently, ethnic conflicts include those where a particular, identifiable group seeks to establish a secessionist movement. For instance, the ethnic Alliance of the Bakongo political party, established in 1955, wanted a Kongo Kingdom covering parts of the DRC, Congo, Angola and Cabinda, with the long-term aim of restoring the pre-colonial Kongo Kingdom of 1390-1857. But other than South Sudan and Eritrea, both of which had distinct ethno-nationalist foundations, secessionist wars have always failed in Africa.

Michael Schmidt is a Johannesburg-based investigative journalist who hasworked in 49 countries on six continents. His main focus areas as an Africa correspondent for leading mainstream journals are emerging and high-end technologies, political developments, conflict resolution and transitional justice, and on the continent’s maritime and littoral spaces.