Innovation: local heroes

Kenyans are used to finding local solutions to everyday challenges and COVID-19 has inspired innovators to find creative ways to cope with the pandemic

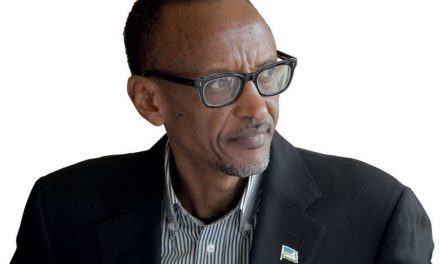

Kenyan fashion designer of “Lookslikeavido”, David Avido, 24, poses for a portrait at his studio in Kibera, Nairobi, on March 18, 2020, with a mask he made, that he creates from remnant of cloth he uses, to hand out to people for free so that they can wear it as a preventive measure against the COVID-19 coronavirus. (Photo by Gordwin ODHIAMBO / AFP)

Onyango Okoth was diagnosed with COVID-19 on 14 July after he visited a hospital in Kisumu for what he claims was a routine medical check. The father of four, who works as a fisherman in Lake Victoria in the western part of Kenya, says he had experienced shortness of breath and high fever the previous day, prompting him to look for treatment. “After receiving initial medical assistance, I was advised to go back home as the hospital facilities were packed,” says Okoth. “The doctors said I was to self-isolate for at least 14 days.” But Okoth, 45, did not know where to start; he’d never heard of self-care. “It was a long, tough and draining struggle with my meagre resources, which had to compete for food, medical equipment and sanitary products,” he told Africa in Fact. Faced with this financial pressure, he says he opted to look for alternative and affordable solutions, particularly a special bed that he had been advised to obtain. Okoth’s story mirrors the daily struggle of many Kenyans in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While more than 30,000 Kenyans had contracted the disease by the first week of September, and there had been 581 deaths, many people had also lost their livelihoods, which has translated to escalated poverty rates. On 1 September, the Kenya Bureau of Statistics said in its Quarterly Labour Force report that unemployment had increased to 10.4% between April and June 2020 compared to the 5.2% recorded in the first quarter of 2020. But even though the crisis has meant sweeping changes to Kenyan society, daily routines and work life, it has also acted as a powerful driver of creative thought and innovation, especially among young people. “As much as we are working around the clock to ensure Kenyans adhere to the COVID-19 protocols and guidelines to contain its spread, we are also challenging young people to come up with innovations in response to the outbreak to stimulate economic and job growth,” says Julius Korir, the Principal Secretary, State Department for Youth.

This, he adds, is being done through training, mentorship, support systems, funding and the creation of an innovation-specific regulatory framework. Acknowledging that innovation is a critical element in providing solutions to ensure better health for all, the World Health Organization (WHO) in the African region held the first in a series of virtual innovation showcases on 21 May that brought together eight innovators and entrepreneurs drawn from Ghana, South Africa, Nigeria, Guinea and Kenya, all of whom had found their own creative solutions to addressing gaps in local responses to COVID-19. Innovations showcased included interactive public transport contact tracing apps, dynamic data analytics systems, rapid diagnostic testing kits, mobile testing booths and low-cost critical care beds.

Among the eight innovators was Gordon Ogutu, 34, from Nairobi’s Githurai slums, who turned to YouTube to learn how critical care beds could be made and improvised locally to fit the demands of the market for people like Onyango Okoth. Ogutu says it was his anger that the Kenyan government was spending billions of shillings to import critical care beds that inspired him to come up with a local solution. Using the know-how he gathered from YouTube, he now makes critical care beds from locally assembled materials. Celebrating the creativity of Ogutu’s work during the event, WHO regional innovation advisor Moredreck Chibi said they aimed at continuing to integrate African innovators into the regional COVID-19 response strategy. Ogutu’s metal critical care beds are designed to provide comfort and safety to both the patient and the caregiver. The design includes a release feature that allows medical teams to flatten the bed at the push of a button or lever and IV poles with hooks to hang fluids and other medication administered via a drip.

Kenyan fashion desiner of “Lookslikeavido” David Avido, 24, creates masks from remnant of cloth he uses, to hand out to people for free so that they can wear it as a preventive measure against the COVID-19 coronavirus, in Kibera, Nairobi, on March 18, 2020. (Photo by Gordwin ODHIAMBO / AFP)

The beds also have removable heads and footboards, which lock safely into place allowing caregivers to tilt the bed and also to adjust the height. “If they (western countries) can do it, then I knew I could also, perhaps even better,” says Ogutu, who graduated from the Kenya Polytechnic in industrial chemistry in 2010. “I gained a lot of knowledge from various online platforms; it was not as complex as I had thought initially.” He told Africa in Fact that the demand for his beds had grown exponentially, with small hospitals as well individuals among his customers. “Impressed by my workmanship, customers have come from as far as 500 km away to order their beds. As a result, I have expanded my workshop labour pool to six, sometimes as many as 15 depending on the orders to be made.” Among his individual customers is Michael Ndwiga, 54, from Embu in central Kenya, who in June had two suspected COVID-19 cases in his family.

He says he purchased the locally made critical care beds from Ogutu after the government announced the plan for patients to be looked after at home due to congestion in hospitals. “Apart from being affordable, they are of good quality, and (quite) similar to those that are imported from abroad,” he said. Ogutu hopes to benefit from President Uhuru Kenyatta’s call on 15 July, which instructed the government to procure 500 hospital beds from local innovators. “The locally made critical care beds are a vital aid to public hospitals that are reeling under the pressure of COVID-19-related admissions,” President Kenyatta said then. The opportunities arising from the pandemic for young innovators have extended beyond critical care beds to locally made surgical masks, which were initially imported, at a relatively higher cost, from the United States, Europe and Asia.

David Avido, 24, a designer and proprietor of the LooksLikeAvido, a Kibrabased fashion firm that focuses on African fabrics, says he took matters into his own hands to produce masks for the people of the Kibra slums after he realised the gravity of the coronavirus. Unlike other businesses driven by return on investment, he told Africa in Fact that he makes and distributes the masks for free. Since March, Avido said, he had distributed more than 20,000 of the items. For his philanthropy, Avido has received a special commendation from President Kenyatta, listed in the 2020 Presidential Citations Order for Outstanding Professionals in Kenya’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. Also among the 68 on the list for the Presidential Order of Service – Uzalendo Award was nine-year-old Stephen Wamukota from Mukwa in Bungoma, western Kenya, who came up with a wooden hand-washing machine to help check the spread of coronavirus.

Wamukota, who came up with the idea after learning on television about ways to prevent catching the virus, says the machine allows users to tip a bucket of water using a foot pedal to avoid touching surfaces, thus reducing the chance of infections. In a bid to enhance innovation, Deputy President William Ruto, in a 24 July tweet, said the government would step up the mentoring and resourcing of micro-, small- and medium-sized businesses and startups “with an appreciation that they are the arteries of our development”. He noted that, due to the biting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy, the government would support and forge partnerships with creative entrepreneurs and businesses, big and small, to support their sustainable growth. Young people across Africa, he said, were exposed to environments that encouraged innovation.

“No doubt in the near future, given proper attention and the right environment, Africa will be the centre of global innovations and inventions, where even vaccines for stubborn pandemics like COVID-19 can be found,” he said.

Mark Kapchanga is a senior economics writer for the Standard newspaper

in Kenya and a columnist for the Global Times, an English-language newspaper

in China. He is pursuing a PhD in investigative business journalism at the

University of Nairobi.