The Robert Mugabe-led government’s response to the Willowgate scandal in Zimbabwe will go down in history as a missed opportunity for setting a precedent of combatting malfeasance. Although there had been earlier corruption scandals, like the Paweni grain supply scandal in the early 1980s, Willowgate is one of the country’s biggest “grand corruption” scandals, with some of its surviving beneficiaries, like Fredrick Shava and Jacob Mudenda, still enjoying the fruits of a culture of clientelism in the form of plum diplomatic assignments and continued service in public offices.

Malfeasance has become endemic in post-colonial Zimbabwe, as evidenced by other scandals dotted between Willowgate and Covidgate (also known as Draxgate, the 2020 COVID-19 medical supplies corruption scandal). There is a structural corruption continuum that has reinforced each president’s hold on power and enabled political elites’ personal enrichment. The evident absence of political will by the two respective presidents to acknowledge and support legitimate anti-corruption citizen initiatives reveals their compromised standing in this regard.

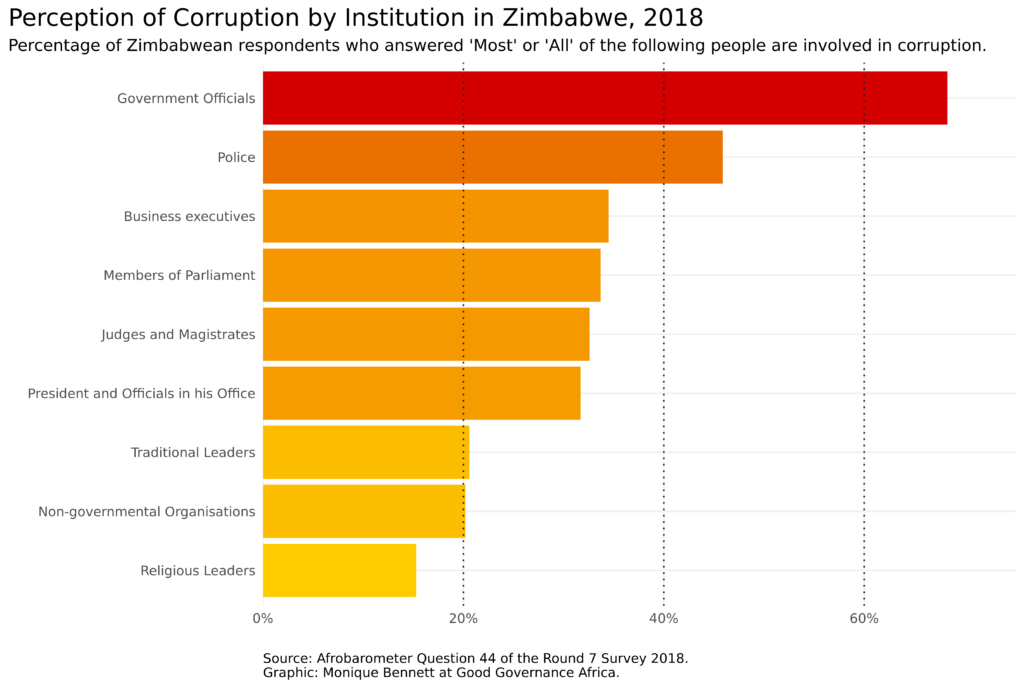

Firstly, President Robert Mugabe consciously and conveniently ignored Willowgate. This scandal occurred only four years after President Robert Mugabe launched the ZANU-PF Leadership Code that he ostensibly instituted to combat corruption after the Paweni grain scandal. The main consequence of him and his ruling coalition’s response to the Willowgate scandal has been the entrenchment, over at least three decades, of a culture of corruption in general, but also malfeasance with impunity. As indicated by the graphic below, the perception of corruption in the very institutions that are meant to uphold the rule of law and minimise malfeasance is widespread among citizens:

Source: Afrobarometer data; graphics by Monique Bennett ©

Mwatwara and Mujere’s analysis of grand corruption in Zimbabwe echoes these sentiments, noting that “in post-colonial Zimbabwe, the scourge has worsened because of the culture of impunity that the current government has established, especially in cases where politicians are involved”. Public resources meant to support critical services in various sectors such as public health and education continue to be misappropriated and plundered without any political will to deter, punish or even recover and restore them to their rightful use of improving services and developing public infrastructure.

The prevalence of malfeasance in the health ministry at such a critical juncture – when the world’s resources are being channelled towards strengthening healthcare systems in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic – has proven beyond reasonable doubt that ordinary citizens bear the greatest brunt of high-level corruption. The 2018 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) notes: “This commitment to saving livelihoods cannot be separated from the political commitment to transparency and accountability towards eradicating endemic corruption for such measures to be affected and effective. Alas, in countries like Zimbabwe and South Africa, clientelism continues to mar such commitment through corruption scandals involving senior government officials and their families.”

Although the Zimbabwean Constitution provides for mechanisms to ensure the integrity and accountability of public officials, the investigations, prosecutions and sanctions of such identified cases has largely remained cosmetic. The government’s response has instead been an onslaught against citizen expression and media freedom. Three decades on, the response is still designed to protect the offender and disable, censor and even punish the whistle-blower. The sense of deja vu in Geoff Nyarota’s dismissal from being editor of The Chronicle after exposing Willowgate and Hopewell Chin’ono’s arrest on 20 of July 2020 for engaging in an unwavering social media anti-corruption campaign, is crushing.

In a bid to ignore the corruption scandal, Hopewell Chin’ono’s arrest was framed conveniently as “inciting public violence” and not as exposing malfeasance. Although he was eventually granted bail after 44 days in pre-trial detention at the notorious Chikurubi prison, the stringent bail conditions that curtail his freedom of movement and bar him from using Twitter are testimony to the risks that accompany investigative journalism and the anti-corruption crusade. Further to this, Hopewell’s case points to how this endemic corruption has eroded, in its wake, the independence of the country’s judiciary.

To ensure the protection of public officials, there is a clear plot to control the operations of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, whose chairperson, Justice Loice Matanda Moyo, is wife to the Minister of Foreign Affairs and November 2017 coup announcer Sibusiso Moyo. It is a clear case of a conflict of interest.

Further to this, there is now a structural threat to the freedom of the judiciary in Chief Justice Malaba’s memorandum directing that all judgments are to be “seen and approved by the head of court division” before being issued. While this was strongly contested, the directive’s threat to the independence of the judiciary is evident in the delays and uncertainties that characterised Hopewell Chin’ono’s case. He was not only denied bail three times but was deprived even of his right to fair legal representation. The targeted personal attacks on his lead lawyer, Beatrice Mtetwa, her intimidation and subsequent barring from representing him, all point to the multi-sectoral cost of malfeasance in Zimbabwe. It has not only eroded the country’s economy but tragically, the independence of institutions that are meant to protect the citizens.

However, the Zimbabwean case confirms that despite the supreme law of the land having clearly defined provisions for combating corruption, this is insufficient. Much more needs to be done, as noted by the IIAG, to combat “the culture of clientelism that has bred continued disinvestment in infrastructure on the African continent”. Transparency International’s Delia Ferreira Rubio observes a correlation between high levels of corruption and weak rule of law, curtailed access to information and reduced citizen participation. Corruption is a threat to citizens’ fundamental rights and freedoms. Transparency International calls for strategies that will nip corruption in the bud, such as putting in place legal frameworks and institutions that reduce impunity for the corrupt and enlarging space for civil society voices as well as entrenching integrity and values through education.

As Zimbabwean citizens continue to dispute the legitimacy of the current government, it is worth imagining a different future, a future in which adequately punitive and judiciously executed consequences (that serve as a sufficient deterrent to corruption) are instituted. The Zimbabwean fight against malfeasance must indeed go beyond the verbal remonstrations characteristic of both eras, and the “catch and release” approach that has largely been a feature of the Mnangagwa regime.

This article originally appeared in Business Day.

Sikhululekile Mashingaidze entered the governance field in Zimbabwe while she was a part-time enumerator for the Mass Public Opinion Institute’s diversity of research projects during her undergraduate years. She has worked with the Habakkuk Trust, Centre for Conflict Resolution (CCR-Kenya), Mercy Corps Zimbabwe and Action Aid International Zimbabwe, respectively.