France, Paris, 2022-02-05. A woman selling flags and posters during the demonstration, Place de la Bastille, organised by Urgences Panafricanistes and M5RFP FRANCE in support of the peoples and perpetrators of the coups in Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea. Photo: Amaury Blin/Hans Lucas/AFP.

In recent years, West Africa has seen a spate of coups and attempted coups. Efforts by governance actors in the region to prevent these incidents have been largely ineffective. Coups are not the only security threat facing the region, and are just one of a variety of emergent challenges, including religious extremism, drug trafficking, and other transnational crimes. Common to these different security threats, however, is that they are a result of the systematic and sustained weakening of constitutional and democratic governance structures.

In a study by security scholar, Patrick J. McGowen (2005), the author lists a total of 44 successful military led coups, 43 failed coups, many of them bloody, 82 coup plots, and seven civil wars and other forms of political conflicts between the years 1955 and 2004. However, the post-2000 era has been a much more stable period, with a significant decline in the number of annual coup attempts. This trend has been reversed with the recent spate of coups in the region.

At the national level, factors such as decline in economic growth, deepening inequality and rising frustration among the citizenry, as explained in one of GGA-West Africa’s latest research studies titled Review of the Security Situation in the West African Sub-Region: Advocating for Security Improvement to Promote Regional Development, have undoubtedly added to political volatility in the region. In countries where economic growth has occurred, only a politically-connected few have benefitted, while the gap between rural and urban populations has continued to grow, with rising levels of inequality seen within healthcare and education. The combined effect of poverty and the ostentatious lifestyle on public display by many in the political elite (a typical example is the lifestyle of the son of the president of Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Nguema Obiang, which has come under scrutiny recently), further drives frustration and the belief that the military is the most viable option to bring about change in the short term.

West Africa’s youthful population, which should propel production and economic growth, is becoming a liability in the face of low levels of employment. With the global rise in religious and violent extremism, youth populations have become a target for recruitment. A lack of clarity around land ownership, and the political and economic marginalisation of peripheral regions, have also added to general instability and consequent public dissatisfaction.

Even in relatively safe, stable and secure West African states such as Ghana, such threats do exist. A typical example is the troubled area of the Upper West Region of Ghana, where age-old have been reignited, causing citizens to worry over the possible infiltration of jihadist fighters from nearby Burkina Faso. This has resulted in the heavy deployment of military personnel and equipment to monitor and arrest any such developments – a heavy toll on the already suffering economy.

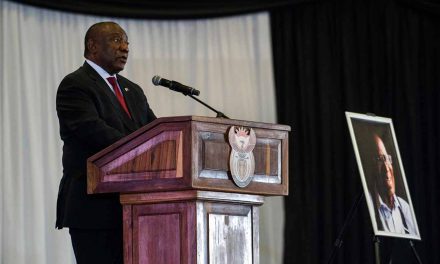

As was the case in Guinea, elements within the military capitalised on public dissatisfaction and, with support of foreign paymasters, were able to oust President Alpha Conde. The covert influence of foreign governments, particularly former colonial masters, in influencing the governance style of free states in West Africa has been cited as one of the factors leading to the breakdown of democracies in the region. France’s influence in French speaking states in regions like Cote d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso has been condemned following political disturbances in these countries at different periods.

While coup leaders have presented their actions as necessary for the protection of the state or the constitution, evidence shows that coup regimes regularly fail to improve economic and developmental standards. Moreover, militaries in the region have a poor track record when it comes to good security sector governance. While recent incidents have placed focus on military coups in the region, it is also important to highlight the rise in ‘constitutional coups’, where democratically elected leaders in the West African region change their respective constitutions to perpetuate their stay in power. A case in point is President Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivoire. In August 2020, President Ouattara, who has been in power since 2011, reneged on his earlier agreement to step down, arguing that his first two term mandates do not count because the country adopted a new constitution in 2016.

Incidents like these could easily trigger another coup, as we have seen in other West African states. President Ouattara is not the only president to attempt changes to the constitution to extend his term limits, and similar actions have been taken by President Gnassingbe of Togo, former President Conde of Guinea, former President Yahya Jammeh of the Gambia, and President Paul Biya of Cameroon.

The weakened oversight role of continental and regional bodies such as the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has a direct impact on the prospects for lasting peace and stability in the region. The ability of such bodies to guide member states to stay on the path of democratic governance and prevent coups should be an urgent priority. The recent flagrant disregard of ECOWAS directives to return to constitutional rule, by military governments like Mali and Burkina Faso, should precipitate significant reforms in the regional body’s modus operandi.

At the recently held Extraordinary Summit of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government in Accra, Ghana, the Authority affirmed its commitment to stand firm for the protection of democracy and freedom in the region, and reiterated its resolute stance in upholding the principle of zero tolerance of ascension of power through unconstitutional means.

However, until this call (protection of the tenets of the constitution of individual states) is supported by all governance actors in the region, and the protocols of the regional body are fully implemented and respected by member states, political instability will likely remain.

[activecampaign form=1]