Local government in South Africa is often seen as the primary interface between citizens and the state. Among its core constitutional functions is ensuring the provision of accessible, high-quality public services such as water, sanitation, and solid-waste removal.

Graffiti that reads “ANC” around a pothole in Johannesburg on March 3, 2023. Photo by Guillem SARTORIO / AFP

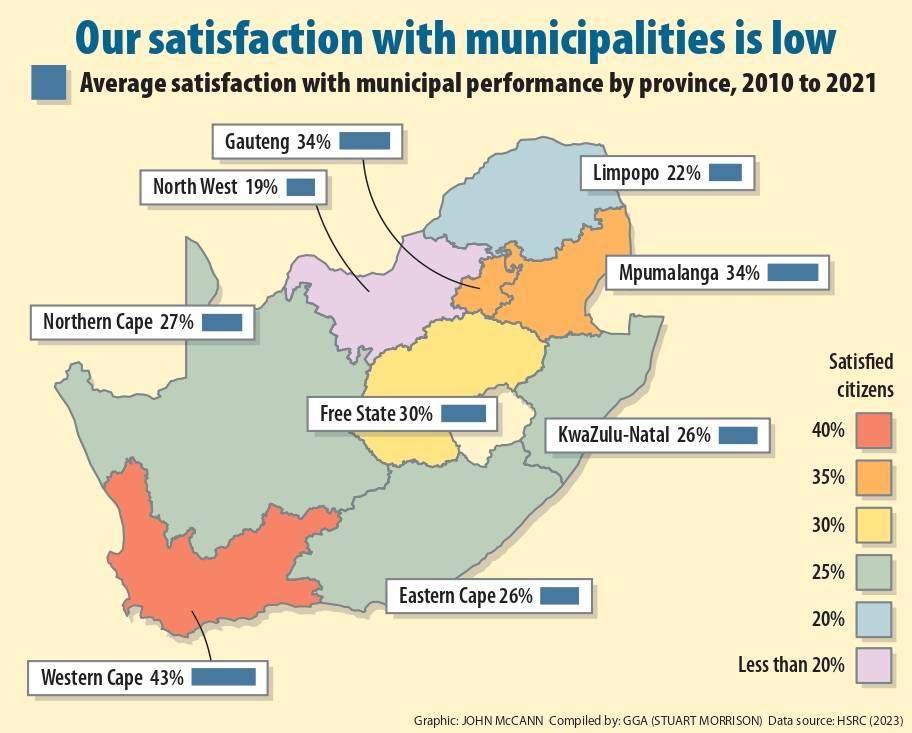

As the map below highlights, however, the low satisfaction with municipal performance is indicative of the various challenges many municipalities face in trying to fulfil this core responsibility.

Part of the problem is that municipalities have not been able to use effective planning, monitoring, and evaluation (PME) frameworks, particularly pertaining to Integrated Development Plans (IDPs).

A forthcoming policy briefing by Good Governance Africa explores the question of how to enhance PME frameworks to improve the provision of service delivery.

The briefing is being released to accompany the launch of Good Governance Africa’s latest Governance Performance Index report. This is an analytical tool developed to evaluate municipal-level governance performance in South Africa.

Local government planning, monitoring and evaluation systems

PME frameworks are vital for any organisation because they better enable them to plan effectively, monitor the impact and success of the plans, and identify key gaps to be addressed.

Since the 1990s, PME systems have become popular in the public sector, especially in developing countries such as South Africa. Policymakers have recognised that, to promote the developmental state and be able to respond to service delivery challenges, governments need to have accurate information.

Apart from PME frameworks being useful tools for enhancing decision-making processes, they also contribute to promoting the democratic values of accountability and transparency.

In South Africa, several regulatory frameworks and pieces of legislation have been introduced to institutionalise PME in every sphere of government.

A core feature of the PME framework at a municipal level was the introduction of IDPs.

Outlined in the Municipal Systems Act of 2000, IDPs form a comprehensive and detailed five-year strategic blueprint meant to be the driving force in implementing the national development strategy.

IDPs were seen as the most appropriate PME mechanism for South Africa by being able to cohere the national strategy with the context-specific issues that various municipalities faced.

As such, it serves as the primary framework for municipalities to identify and set key developmental goals, plan for service delivery execution and financing that ties into the overarching provincial and national strategies.

It also provided helpful indicators to measure the performance of the municipality and to promote civic participation by ensuring that community members were a key part of the IDP development and review processes.

The problem

The inception of IDPs starts after a local election, in which the newly formed municipal council facilitates the creation of the plan by consulting various stakeholders and conducting an extensive socio-economic assessment of the community, after which it is submitted to the provincial government for review.

However, while municipalities regularly submit their IDPs, they are often unable to implement them.

For example, in Emfuleni, Gauteng, more than 100 projects were proposed within a 10-year period but none of them were implemented. Upon further investigation, it was found that the plans set unrealistic targets from a temporal, financing and execution point of view.

This points to several underlying problems surrounding IDPs.

There seems to be an overemphasis on compliance with drafting them rather than implementing them.

This is further confounded by the fact that there is a lack of adequate human resource management, insufficient intergovernmental cooperation and a tendency to overemphasise the planning component at the expense of monitoring and evaluation.

Together, these issues affect the ability of municipalities to improve their service delivery capabilities to meet the changing needs of the communities they serve.

The consequences of underperforming municipalities, especially in the light of the growing economic challenges, include mistrust and citizen discontent with local government, as well as increased protest action and instability.

Way forward

Good Governance Africa’s policy briefing highlights several key recommendations to address the discrepancies in the PME framework.

To tackle the lack of effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms within the IDP structure, we believe there needs to be greater buy-in from municipal management.

Local governments are generally responsible for implementing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and, as such, if they are not fully on board they will be less likely to implement such mechanisms.

One approach to promote buy-in among the municipal leadership would be for the department of co-operative governance and traditional affairs to develop a national capacity-building strategy.

This would help prioritise effective monitoring and evaluation systems as crucial to the success of the municipality.

Many local municipalities outsource the development of IDPs to external partners to address the lack of human resources and expertise. While external assistance is often needed in the short term, this practice often comes at the expense of not being able to fully reflect the needs of the local community.

Therefore, to address issues surrounding external partners, the national government should consider implementing a framework to improve oversight. Within this, municipalities would be able to develop their own systems to minimise the risks associated with external partners.

Our policy briefing also highlights how independently developed reports, such as the Governance Performance Index, can help lay the foundation for action.

Municipalities might consider adopting their own self-evaluation mechanisms that could improve future performance as measured by the index.

For instance, they could build governance registers to bake in adherence to the King IV Code of Good Governance, along with the Municipal Finance Management Act and other guiding legislation.

This might not prove an entirely sufficient condition for improved performance but it would increase the probability thereof.

PME systems in democratic societies require the participation of the community to work effectively. The current legal framework does have provision for community participation. However, such efforts need to be strengthened to support it.

One approach to improving community participation is to craft a citizens’ charter, which could help facilitate consultation with the community through the IDP process.

It could help ensure accountability as well as increase trust within local government as it would make it easier for citizens and municipal leaders to engage through official forums while including citizens within the decision-making process.

Furthermore, the national government should consider the role it plays in incentivising municipalities to develop innovative solutions.

It could support municipalities in fostering public participation beyond wider strategies and frameworks.

For example, it could create a programme that celebrates and rewards improved citizen participation, similar to the discontinued Municipal Performance Excellence Awards.

While the strength of our democracy begins with the ballot, it does not end there, thus such initiatives can also be useful for fostering civic engagement beyond voting, especially at a local level.

Local government is vital to ensuring the national development goals are effectively implemented. However, such an alignment requires a robust and comprehensive PME system. IDPs provide a key framework for such systems to be effective.

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, the shortcomings described above need to be addressed through building leadership capacity, expanding regulation, and prioritising community participation.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian on 14 March 2024.

Stuart Morrison is a Data Analyst Intern within the Governance Insights and Analytics Team. He is currently completing his Master’s degree in e-Science at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. His thesis is focused on exploring the relationship between early elections and the propensity for political violence. Stuart also has a keen interest in applied data science and aspires to use his skills as a data scientist and researcher to help address some of the key security and governance issues across the African continent.