On Friday 29 September 2023, the Kingdom of Eswatini will hold its next general elections. A landlocked country in Southern Africa, Eswatini reports a total population of approximately 1.2 million – the second smallest of any non-Island African nation. Ahead of the upcoming general elections, Good Governance Africa is providing a series of analysis pieces. By drawing on data presented through a series of visualisations, this piece offers an overview of the current state of Eswatini, with a focus on governance, healthcare, economic well-being and public sentiment.

Governance

The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), provides annual scores for all countries in six categories: Political Stability and the Absence of Violence/Terrorism (PS), the Rule of Law (RL), Regulatory Quality (RQ), Control of Corruption (CC), Government Effectiveness (GE) and Voice & Accountability (VA). Countries are scored on a scale ranging from -2.5 to 2.5, with higher scores indicating better governance in a given year. On most indicators Eswatini scores lower than both continental and global averages.

However, even when analysing Eswatini’s performance on these indicators over the last 15 years, it is especially noteworthy how much lower the country tends to score on Voice & Accountability compared to its performance on the other five indicators. According to the WGI, the VA indicator “captures perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media”. Evidently, Eswatini’s lower performance on this indicator is directly related to the lower levels of political freedoms that the country provides, an especially pertinent point ahead of next week’s elections.

Health

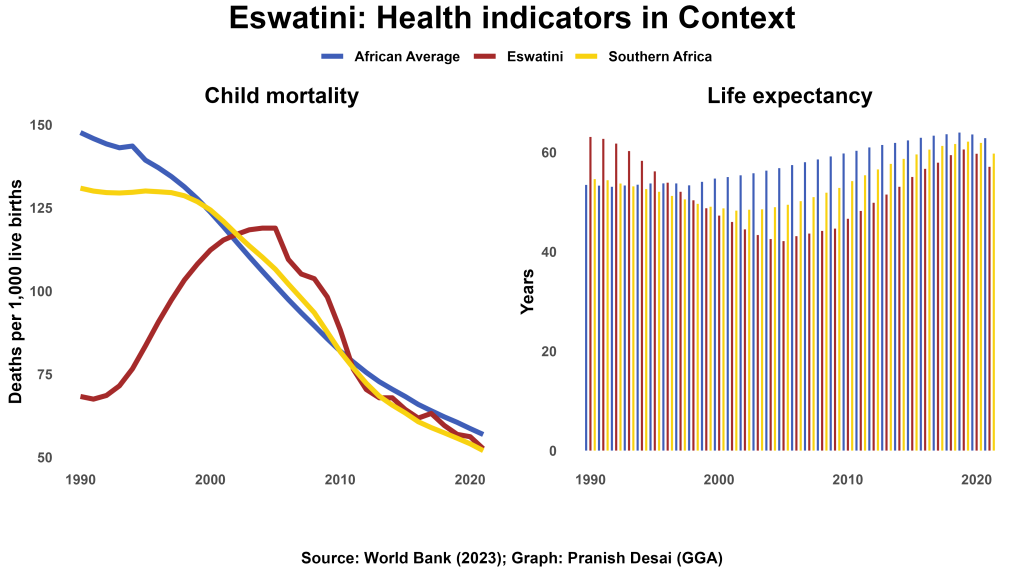

The HIV/AIDS epidemic has been one of the defining events within Southern Africa over the last three decades. Eswatini is no different in this respect. In fact, at one point in the mid-2000s, a UN Aids envoy indicated that the country had the highest rate of HIV infection in the world. Looking at Eswatini’s child mortality rate and life expectancy offers us a glimpse of the devastating effect that the disease had on the country. In 1990, Eswatini had a much lower child mortality rate than its Southern African peers, and when compared to the African average. The same held true in terms of life expectancy with Eswatini reporting an average of 63 in 1990, nearly ten years more than either the African or Southern African averages.

The impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on life expectancy was acute, with overall life expectancy plummeting to a low of just 42 years in 2005. For comparison, the African average in that year was nearly 57. Since the mid-2000s, Eswatini and Southern Africa have had more success in curbing the spread of the disease, but overall life expectancy continues to lag behind the continental average. Similarly, in an era when African countries made great strides in reducing child mortality, Eswatini actually saw its child mortality rate balloon during the 2000s. Over the long-term, the epidemic also continues to have an influence on the demographics of the country, with population growth noticeably slower in recent years.

The Economy

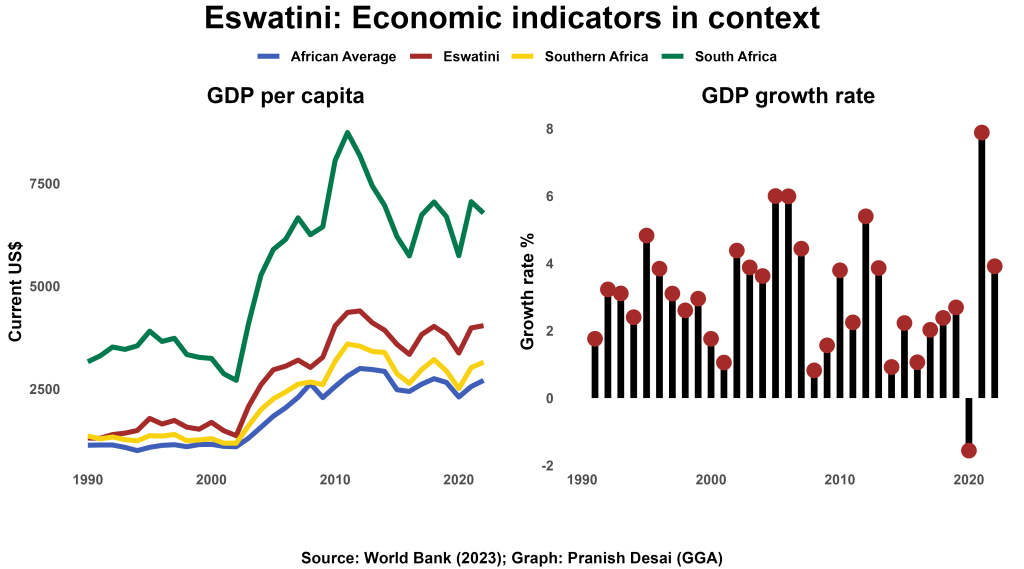

In terms of the economy, there are two aspects worth highlighting from a data perspective. First, how Eswatini’s economy has performed in a time of global and regional economic turmoil, and second, its economic reliance on neighbouring South Africa, particularly in trade. Over the last thirty years, Eswatini has maintained a generally higher GDP per capita than its peers in both Southern Africa, and the continent as a whole. However, even in this context, it is noticeable how closely fluctuations in Eswatini track with regional trends (which report a 10-country average), and continental trends (which report a 54-country average). Contrast this with neighbouring South Africa where average income trends reflect a generally more autonomous pattern. To a considerable extent, this contrast is a function of South Africa having a larger and more diversified economy, while Eswatini is less economically diversified and more sensitive to regional trends. On a more positive note, Eswatini managed to maintain nearly three decades of consistent economic growth until the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted this trend.

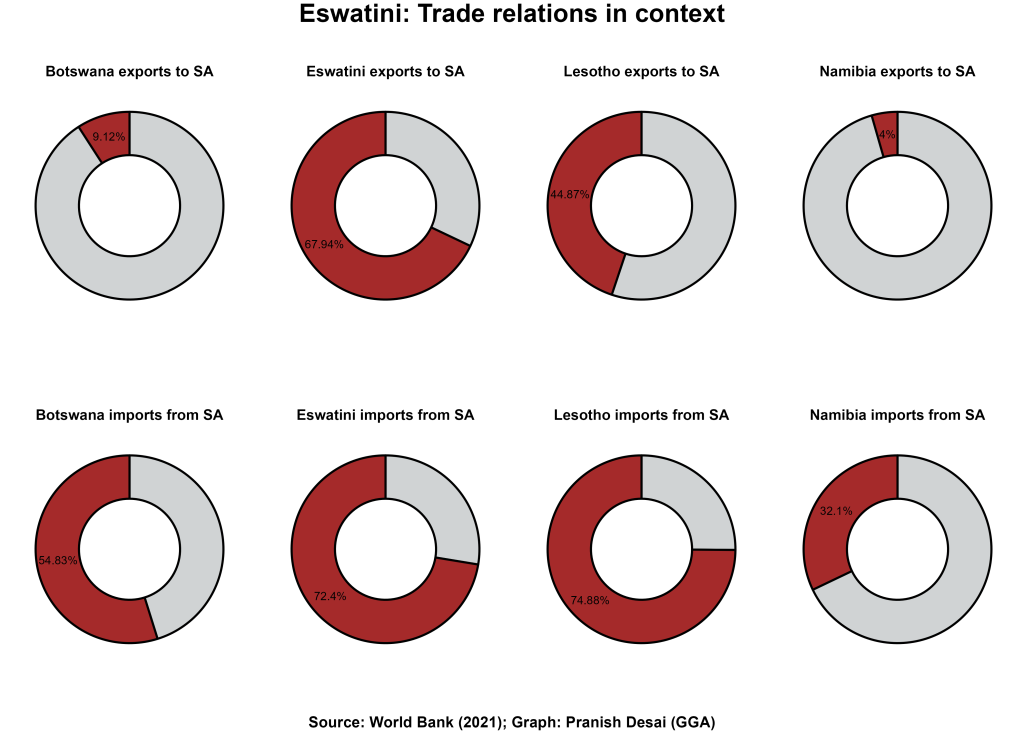

The reality of Eswatini’s economic reliance on South Africa is especially well made in the context of its trade relations. Exports to South Africa account for nearly 70% of Eswatini’s total exports, while more than 70% of its total imports were from the same country. In terms of trade, the most appropriate “peer group” for Eswatini are three other countries within the Southern African Customs Union (SACU): Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia. Although most of these countries have a population which is roughly double that of Eswatini, they are all low-population countries within the broader regional, continental and global context. For each SACU country, South Africa is a top 5 export destination. However, Eswatini’s relative reliance on South Africa as an export destination is 1.5 times more than Lesotho’s, 7.5 times more than Botswana’s and nearly 15 times more than Namibia’s. For as long as this pattern continues, Eswatini’s economic destiny will be inexorably tied to that of South Africa.

What do citizens think?

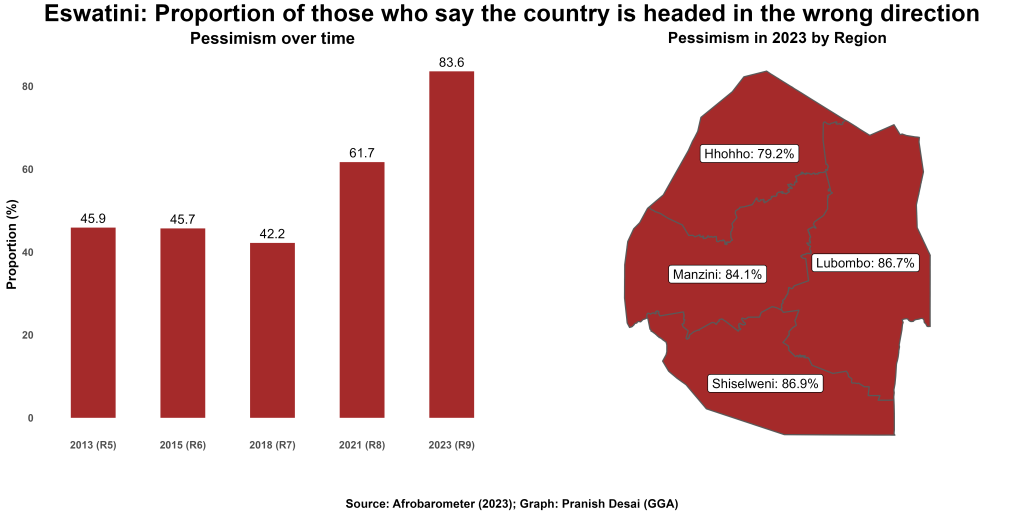

Equally as important as the realities of governance, health and the economy are what citizens think of the state of their country. Citizen sentiment has a crucial role in determining the legitimacy of a particular government, monarch or political system. In this respect, there are some concerning signs for the Eswatini government. According to data collected by Afrobarometer, there has been a discernible increase in the proportion of survey respondents who say that they think Eswatini is headed in the wrong direction. Even accounting for the +/-2.8 percentage points margin of error which Afrobarometer data maintains, the change between 2018 and 2023 has been particularly dramatic, with the number of pessimistic respondents essentially doubling as a proportion of total respondents. Furthermore, this disaffection is widespread across Eswatini’s four main regions.

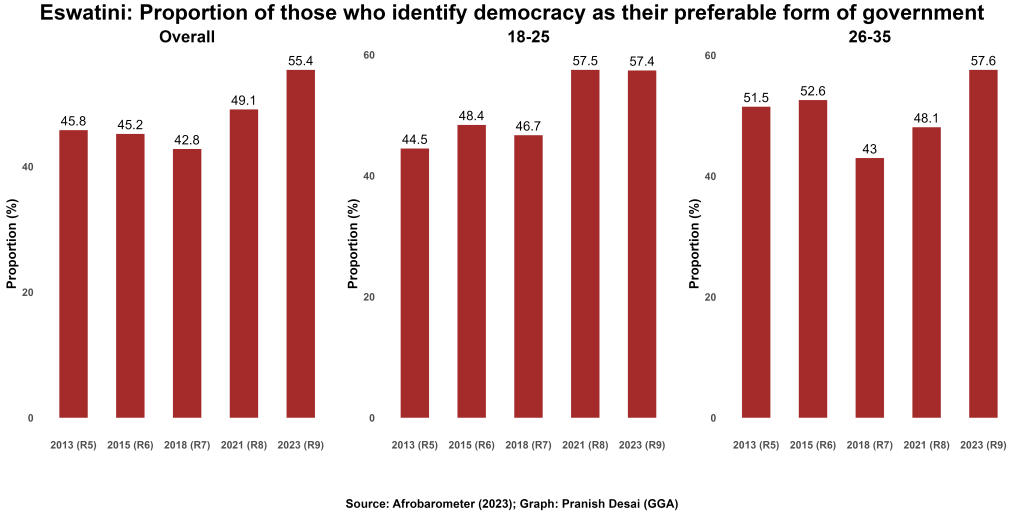

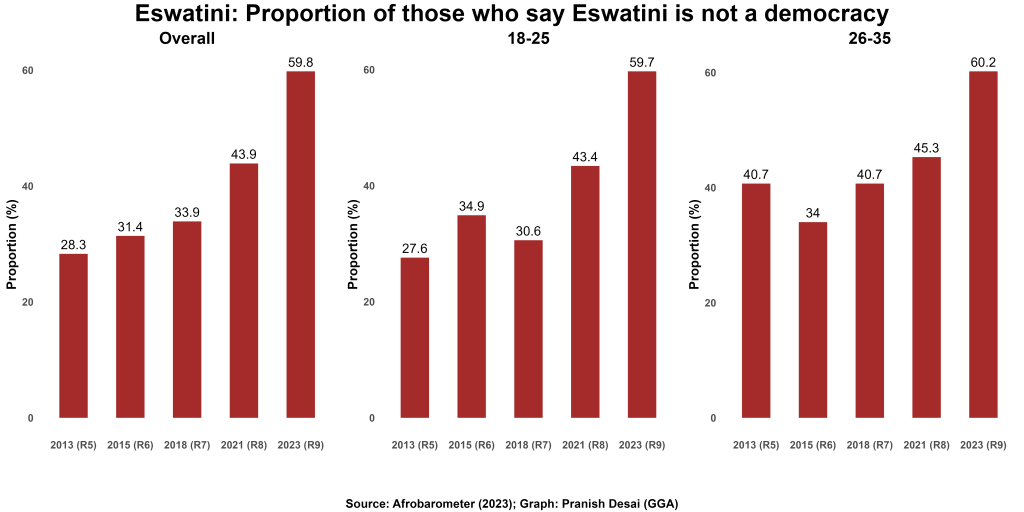

Another area that the Eswatini government will need to pay attention to is the growing disparity between popular support for democracy and the perception that many citizens hold that Eswatini is not a democracy. In the most recent Afrobarometer survey, conducted in 2023, more than half of all survey respondents chose democracy as their most preferred form of government, with this support rising slightly among younger respondents. This age-related effect is noteworthy considering that the United Nations World Population Prospects estimated that nearly 60% of citizens are under the age of 25.

However, there is also a consistently rising proportion of respondents who consider Eswatini a non-democratic country. This perception is growing across all age groups. It has been particularly notable in the aftermath of the wave of protests sparked by the death of the student Thabani Nkomonye in 2021. The assassination of the former chair of the pro-democratic Multi-Stakeholder Forum, Thulani Maseko in January 2023 is another moment which may have contributed to a growing proportion of Eswatini citizens reporting their dissatisfaction with the direction the country is headed in.

The more such disaffection endures, the greater the likelihood that pressure will grow for Eswatini to institute meaningful reforms which can foster effective public participation in the politics and governance of the country. Adopting a proactive and pragmatic approach will give Eswatini the best chance of striking the right balance between its existing institutions and traditions, and the greater desire for democratic reforms which younger citizens are more likely to express.

Pranish Desai is a doctoral student in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His core areas of focus are in comparative politics and political methodology, with a specific interest in the politics of Southern Africa. Between 2021 and 2024, Pranish held several key positions within the Governance Insights and Analytics programme at GGA. In these roles, he was centrally responsible for the elevation and enhancement of the Governance Performance Index as GGA's flagship governance assessment tool. Before departing GGA, Pranish also played a key role in the development of our strategic framework for the 2024-2028 period.