One rule for the ruler…

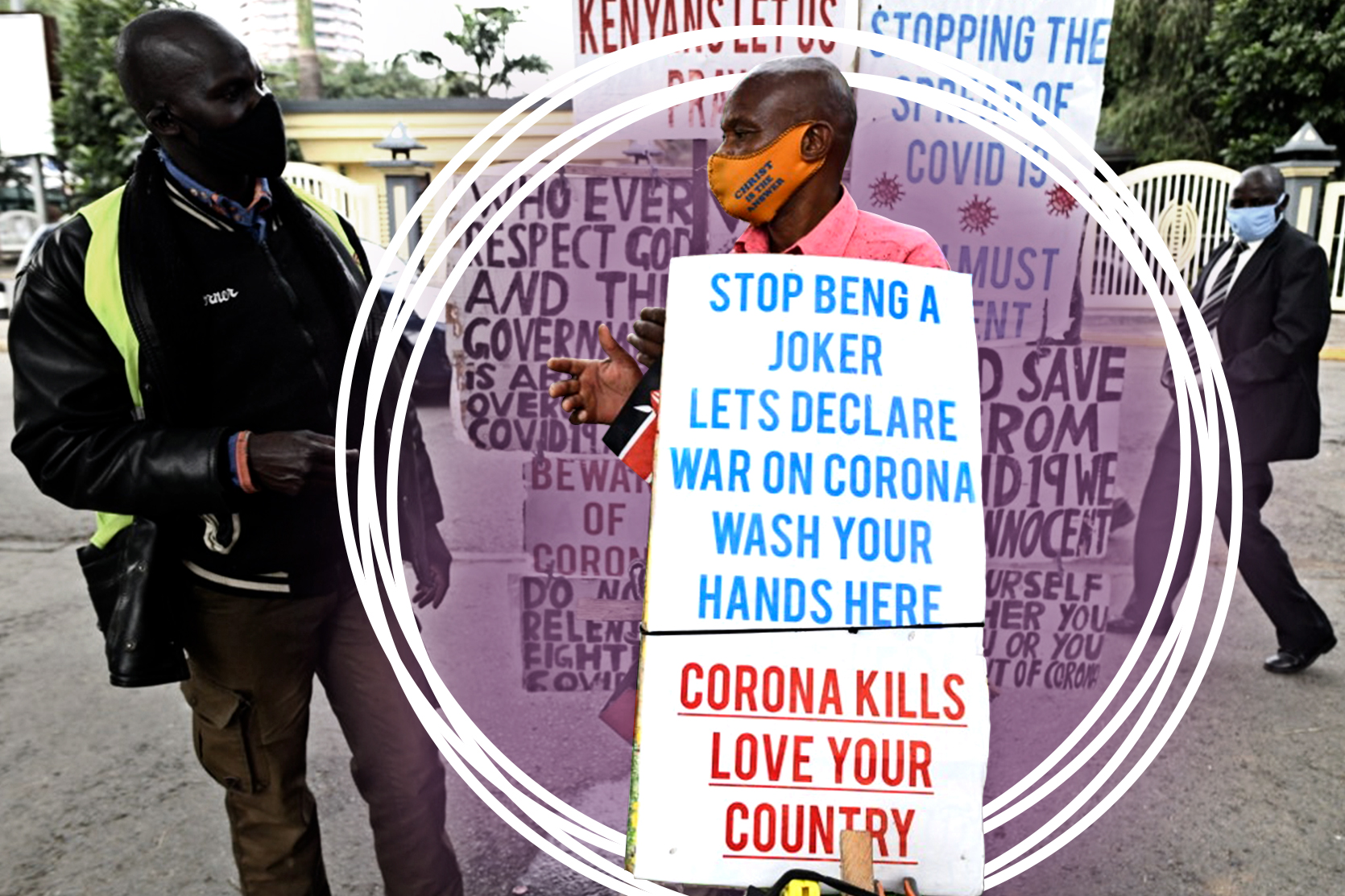

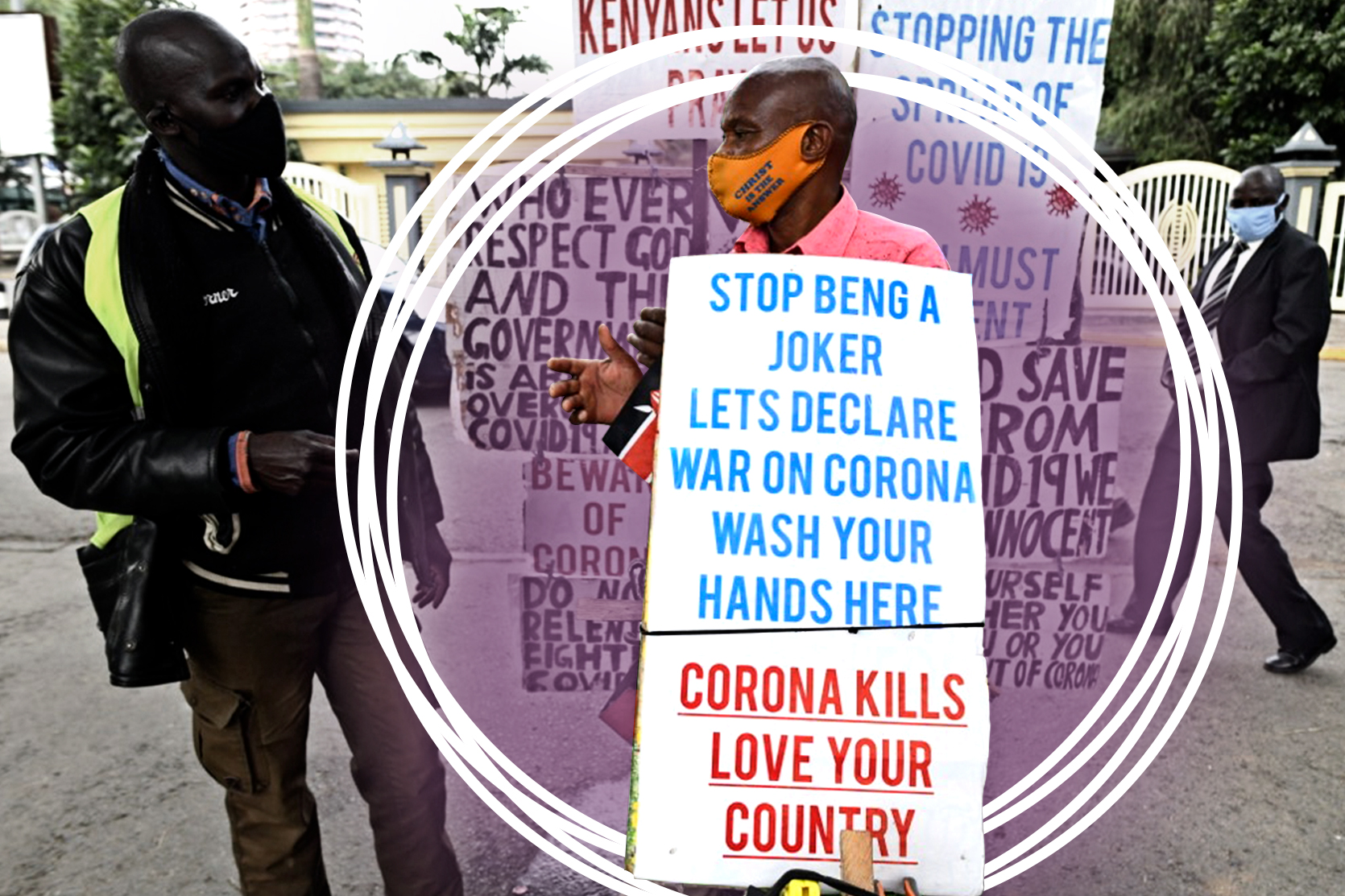

The Kenyan Twitterverse turned into a furnace on 15 June after the Kenyan opposition leader, Raila Odinga, displayed his Covid-19 test results on social media and appealed to the people to take tests, sanitise and observe social distancing.

Some commentators reminded Odinga, one of the country’s major political figures, that the negative result did not show that he was immune to the coronavirus. Dr Lukoye Atwoli, associate professor at the Moi University College of Health Sciences, said the negative result meant that “the virus was not detected in the samples collected from an individual at a particular time”.

On that basis, he noted that the COVID-19 “negative certificate” was worthless beyond confirming that the person, at the time of testing, was unlikely to be infected. The Twitterfever had hardly tapered off when State House said four staff members had contracted the disease. However, “His Excellency the President and the first family are safe and free from Covid-19.”

The Twitterfever had hardly tapered off when State House said four staff members had contracted the disease.

To reinforce the outbreak’s containment measures, State House spokesperson Kanze Dena Mararo said auxiliary access protocols for State House staff and visitors had been introduced. But the announcement soon set another Twitterfire burning as Kenyans mocked President Uhuru Kenyatta for breaching the basic guidelines included in executive orders aimed at taming the spread of the deadly disease, especially as regards restrictions on movement.

Most political leaders seem to have adhered to the movement restrictions. However, people dear to the president’s circle continue to disregard the rule of law, as well as Ministry of Health directives on Covid-19 by holding public gatherings across the country. Currently, many governments are restricting gatherings, based on the understanding that up to 80% of infections result from so-called “super-spreader” events, which are “mostly … indoor gatherings in which lots of people from different households [a]re in close, extended contact, such as religious services, birthday parties, and choir practices”, according to one report.

People dear to the president’s circle continue to disregard the rule of law, as well as Ministry of Health directives on Covid-19 by holding public gatherings across the country.

At State House in Nairobi, for instance, the president recently conducted two separate meetings with members of the National Assembly and the Senate. He seemed to want to reprimand “errant” members of these bodies for apparently inclining to his deputy, William Ruto. The latter is thought to have “disrespected” the president by focusing on continuing his campaign for the 2022 general elections instead of focusing on serving the electorate. A third session, bringing together the governors of the county governments, deliberated on ways to combat the pandemic.

Ironically, on 10 June, the same day governors converged on State House, a warrant of arrest was issued against former Kakamega Senator Dr Boni Khalwale, an ally of Ruto, for “breaching” the government’s guidelines on public gatherings by distributing food to the vulnerable in western Kenya. This reflects a drift toward “one rule for the rulers, another rule for the ruled” that one sees occurring in other countries around the continent, as reflected in the other blogs in this series, for example.

This reflects a drift toward “one rule for the rulers, another rule for the ruled” that one sees occurring in other countries around the continent.

In early June, the senior coordinator of the Africa Bureau of the US Agency for International Development, Christopher Runyan, warned that some African governments were using the coronavirus pandemic to erode democratic freedoms. He pointed to “disturbing” trends, including the muzzling of the media, the cancellation or postponement of elections, targeted crackdowns on key population groups, and increased gender-based and criminal violence. [Editor: Check out Reporters without Borders’ Tracker_19 for an updatable map of repressive measures against the media.)

It is worth remembering that in the wake of the coronavirus disease outbreak, Kenya came up with drastic measures to confront it. As at 16 May 2020, President Kenyatta had addressed the country six times, reiterating the state’s determination to cushion the people against the dreadful effects of the Covid-19 crisis.

He pointed to “disturbing” trends, including the muzzling of the media, the cancellation or postponement of elections, targeted crackdowns on key population groups, and increased gender-based and criminal violence.

The president has implored Kenyans to stick to the guidelines provided by various government agencies. It may be that the guidelines — a product of various directives, policies and laws on public health, fiscal policies, social status and the administration of justice — have played an important role in managing the spread of the disease in Kenya since the first case was reported on 13 March, 2020.

According to the Cabinet Secretary for Health, Mutahi Kagwe, the infection rate would have been far higher than the current 3.14%. As at 15 June, Kenya had recorded 3,727 positive cases, out of 118,701 samples, with 1,286 recoveries and 104 deaths.

Appreciating that “the virus is unforgiving, and its rate of growth if not arrested is exponential”, Kenya has come up with a number of legal notices that restricted the movement of people. To supplement the executive’s directives, the judiciary, too, issued circulars on the administration of justice to facilitate smooth operations in courts.

But these guidelines, supported at they are by a range of legislation, have been perceived as applying to some, but not others. Aside from the State House assemblies, politicians who enjoy the president’s political warmth — among them Cabinet Secretaries Fred Matiangi, Sicily Kariuki, Joe Mucheru, Eugene Wamalwa and James Macharia — have also been roaming across the country “launching development projects”.

Politicians who enjoy the president’s political warmth have also been roaming across the country “launching development projects”.

At these gatherings, “big” people appear exempt from protocols such as social distancing and the wearing of masks. Meanwhile, reports indicate that the police are arresting, harassing, brutalising and extorting bribes from members of the public for petty matters, such as “inappropriately fitting” face masks.

This selective application of the law has brought the executive into increasing conflict with the country’s judiciary. Law Society of Kenya President Nelson Havi has argued that “toxic” advice by the Attorney General to the executive has helped this selective approach to the law to gain currency during the Covid-19 crisis. On June 8, Chief Justice and President of the Supreme Court of Kenya, David Maraga, bluntly criticised President Kenyatta at a press briefing for thinking that he could “cherry pick judges”.

Clearly angry, Maraga said the government had formed the bad habit of “routinely disregarding court orders”, citing the eviction of more than 1,000 families from the Kariobangi area in Nairobi, “all in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic”. President Kenyatta, he added, had adopted an attitude of “what will you do about it?” The head of the state had no choice but to respect the laws of the land because he had sworn “to defend and uphold the Constitution and the laws of Kenya”, Maraga said.

Will the president, his government, and its various agencies, including the police, heed these warnings? Time will tell.

We’d love to hear from you! Join The Wicked Conversation by leaving your comments below, or send your letter to the editor to richard@gga.org.

Mark Kapchanga is a senior economics writer for the Standard newspaper

in Kenya and a columnist for the Global Times, an English-language newspaper

in China. He is pursuing a PhD in investigative business journalism at the

University of Nairobi.

People outside Kenya have difficulty in understanding the ethnic politics and all that flows from that. It is almost as if the Kikuyu elite has taken the place of the former colonial power in the economic strength and the selective government of the country.

Hi M.Whisson,

Many thanks for your response.

Kikuyu tribe is not only the most populous in Kenya but it also enjoys the political and economic powers. Almost all key government departments are controlled by this tribe. However, this narrative is changing now especially after Uhuru Kenyatta, also a Kikuyu, came to power (in 2013). Kikuyus realised that the Kenyatta and other influential families have been using them to grow their wealth at their expense. It is no wonder that the President today does not enjoy the support of Central Kenya (a region that is chiefly occupied by Kikuyus).

*Reply from Mark Kapchanga