A cow stuck in muddy waters in the drying Mabwematema dam, Zimbabwe, on 25 December 2019. Drought is one of the devastating impacts of climate change. Photo: Zinyange Auntony/AFP

After being postponed by a year due to COVID-19, the United Kingdom will host the long-anticipated 26th annual United Nations Global Climate Summit (COP26) in Glasgow in November. Experts agree that the window for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels is rapidly closing, and the decade to 2030 will be the most critical to achieving this target.

Most scientific models predict climate catastrophe if temperatures continue to rise at current rates. Countries least vulnerable to the impacts of climate change are among the highest global greenhouse gasses (GHG) emitters, and conversely, those most vulnerable are the least responsible for its genesis. The Summit is widely viewed as the world’s last chance to get climate change under control.

Broken promises

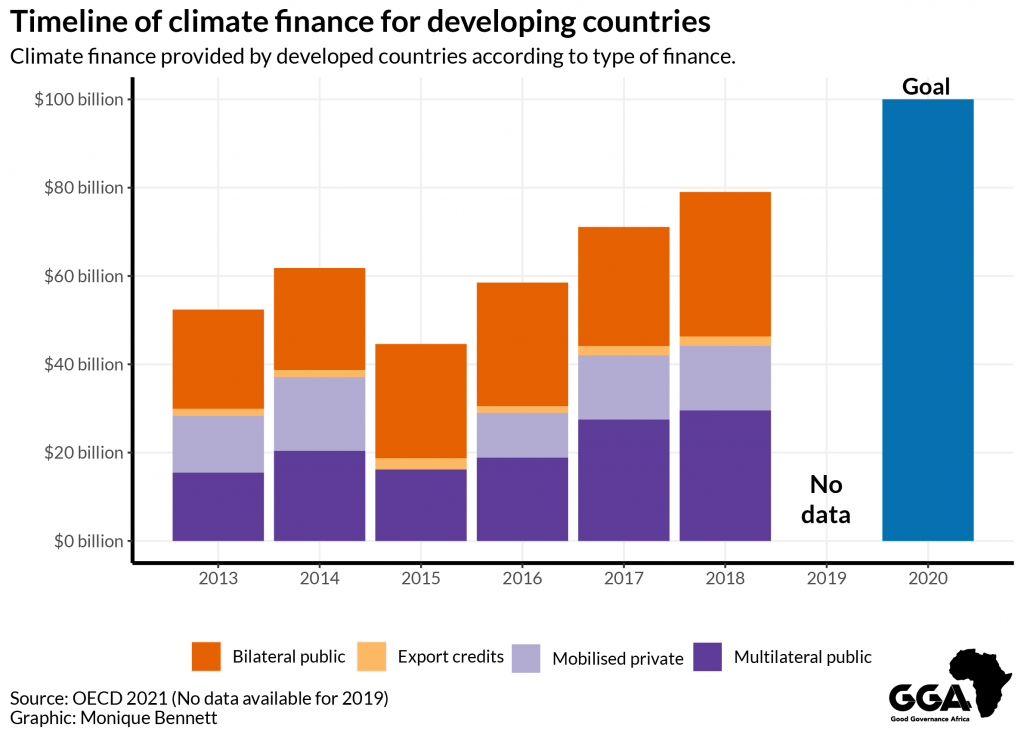

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and in line with the 15th Conference of the Parties, developed countries agreed to jointly mobilise $100 billion per year by 2020 to provide financial resources and support climate action in developing countries. However, analysis by Oxfam estimates that, based on current pledges and plans, developed nations will continue to fall short of the 100$ billion goal by 2025 (reaching only $93 to 95$ billion)— five years after the goal should have been met.

According to the OECD report (2021 ), the highest amount accounted for was in 2019 with developed countries mobilising $78,9 billion of climate finance, an increase from $71.2 billion in 2017, see figure below. Data for 2019/2020 will only be made available in 2022. This suggests that the $100 billion goal is unlikely to be met by the end of 2021. Downplaying the importance of the required amount can create debt for developing countries as they attempt to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is promised vs what is required

The $100 billion is only a fraction of the amount needed to assist developing countries transition to low carbon economies and address the impacts of climate change. A recent study by Meridian Economics estimates that South Africa alone will require over $750 billion to finance a just transition.

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted both developed and developing states’ climate financial commitments. Demands created by the pandemic diverted resources that may otherwise have been allocated towards international climate finance or national climate action initiatives (Gilder & Rumble, 2021). For example, the UK reduced its international aid by 30%. And in some countries, economic recovery stimulus packages failed to provide finance for green development.

Efforts to “build back better” and accelerate the transition to low carbon economic trajectories were therefore hindered. How the international community engages the financial sector to allocate capital to manage physical climate risks and seize opportunities in the transition to net zero will be critical.

In this respect, there have been some positive developments from developed countries/partners:

- The United States has promised to double its contribution of $5,7 billion USD to $11,4 billion USD a year by 2024.

- The UK has committed to £11,6 billion over the next five years.

- Based on the 2017/2018 climate finance progress, the Overseas Development Institute notes that Norway, Sweden and Germany have given a “fair share” of their contribution to the $100 billion USD target.

- Canada has successfully delivered on its 2,65 billion CAD commitment and promised to double it to $5,3 billion CAD over the next five years.

The commitments made to address some of the climate crisis impacts does not close the funding gap, neither is it enough to cover Africa’s 54 countries – many of which are already battling Covid-related economic setbacks. Missing the collective target will only erode the trust between developed and developing nations. Developing nations have expressed the inability to reduce emissions without the support of wealthier nations. Therefore, a more rigorous and clearer framework around climate finance is needed to foster accountability among wealthier nations to deliver on these promises.

Climate Finance and Africa’s position

This summit is the most pressing moment for African countries. If African countries are to contribute to global efforts to mitigate climate change, developed nations who have benefitted from this climate inequality have a moral imperative to provide financial and technical support. Mitigation efforts must simultaneously serve to create adaptation initiatives which are robust, sustainable, and put the continent on a positive development trajectory.

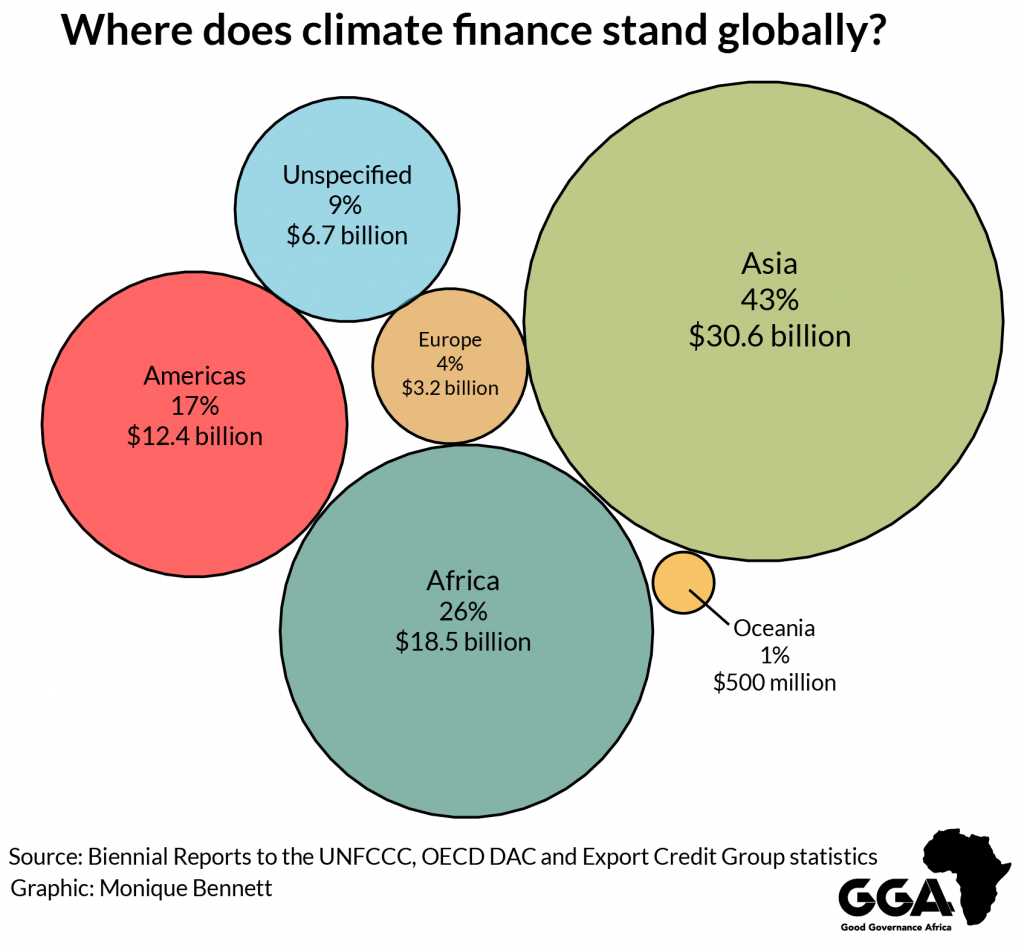

African countries’ negotiation teams that will represent their countries at COP26, and the international funding community, need to consider funding levels that are appropriate for Africa. Africa was the second largest beneficiary of climate finance from 2016 to 2019, accounting for 26% of global climate funding as shown in the figure below. However, given the individual requirements of its 54 nations, much more is required. According to the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), Africa’s adaptation costs could potentially reach $50 billion a year by 2050.

Any decision taken on financial resource allocation will either make or break African states’ attempts to transition to greener economies. Africa should push for more robust climate finance commitments and disbursements that will meet its mitigation and adaptation needs.

Estimates suggest that Africa will lose about seven years’ worth of development due to the COVID-19 pandemic, hindering the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate action targets. The pandemic revealed a number of pre-existing structural issues which have a bearing on climate change responses:

- International funding (for development requirements) is lacking. Finances received by developing countries were inadequate to address the negative socio-economic impacts of covid-19.

- Lack of internal and operational capacity in recipient nations. When funding was availed it exposed weak state capacity and dysfunctional institutions within governments.

- Corruption and greed. The pandemic exposed greed and corruption by political leaders, government officials and within the private sector. In South Africa, government procured PPE goods and stimulus packages, from which government officials benefited millions of Rands at the expense of the intended beneficiaries of those packages.

The mobilisation of larger funds is crucial for Africa’s transition. For the continent to develop stronger climate ambitions and green deals in these daunting circumstances, financial preference needs to be given to African countries. It is therefore important that current funding mechanisms are reviewed and reconsidered to benefit Africa’s development growth in the long run. At the same time, African countries will have to demonstrate that they are capable of spending climate finance in responsible ways, and do not merely redirect those resources towards unproductive activities or divert them for corrupt ends much to the detriment of sustainability.

Leleti Maluleke is a Researcher for our Human Security and Climate Change programme. She completed her Bachelor of Political Science in Political Studies in 2017, and her Honours in International Relations in 2018 at the University of Pretoria. She started her career at International SOS in the Security Services department as a Political Risk and Security Intern. Socially, her countries of interests include Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi.