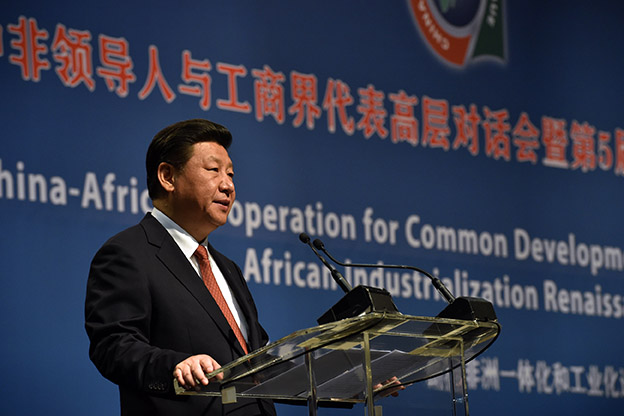

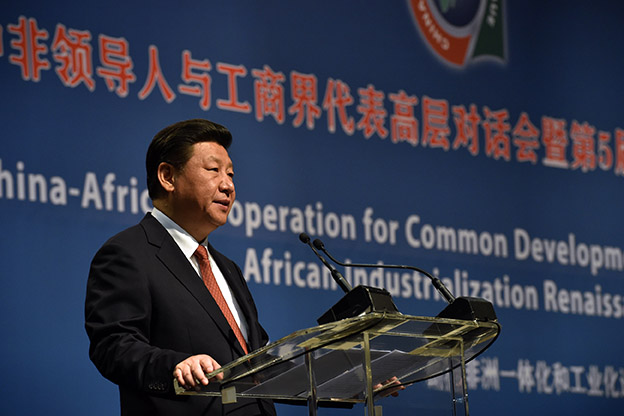

President Xi Jinping addressing the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation business summit in Johannesburg in 2015. Image Elmond Jiyane, GCIS

African countries find China’s loan conditions to be far less onerous than the IMF’s, and the Asian country is digging deep to fund social development and industrialisation on the continent, for a price

Less than a year after launching a rail project partly funded by China at $500 million, Nigeria has announced a new $7,8 billion loan from China’s state-run EXIM Bank. The new deal, pending parliamentary approval, will fund a standard gauge rail between Lagos and Kano, the country’s two most populous cities. Rotimi Amaechi, transport minister, announced the new deal in February this year. This follows a 2016 deal with the Asian nation to fund an $11,1 billion railway from Lagos to coastal Calabar.

Over the past decade, China has spent billions of dollars on loans for infrastructure funding across Africa. These include a $3,8 billion railroad in Kenya, a $7 billion port in Tanzania, and a $3,1 billion dam project in Mozambique. The Nigerian projects are amongst the newest ones. Between 2000 and 2014, China delivered $94,5 billion in loans to Africa, according to the China-Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. In 2014, Beijing unveiled a $12 billion funding package for Africa, and in 2015, it announced $60 billion in loans and aid to the continent.

As their economies have grown in the past two decades, African governments seeking to build badly needed infrastructure have found a willing lender in Beijing. In doing so, they have pushed to minimise, if not end, their dependence on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Experts say that the shift is largely due to China’s funding model, which provides multi-billion dollar credits at more flexible terms, even to countries otherwise restricted from big money by the IMF. “African countries seem to increasingly prefer loans from China mainly to avoid the very constricting neoliberal conditionality that goes with loans from the IMF,” says Chibuzo Nwoke, professor of international relations and vice chancellor of Oduduwa University in Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

For years the IMF prevented low-income countries from taking up non-concessional, large-size commercial loans. And as other Western lenders often rely on the international financial organisation’s assessment of countries’ macroeconomic policies and readiness for reforms, African countries are increasingly looking elsewhere for finance.

The IMF’s required reforms included open markets, scrapping government subsidies, deregulating key sectors, privatisation and debt management. For the IMF, low-income countries must seek debt relief before they look for new loans, and countries must abide by a debt limit framework to benefit from debt relief.

Martin Uhomoibhi, president of the Pan African Institute for Global Affairs and Strategy in Abuja, says that the “so-called Washington Consensus or IMF ‘prescriptions’”, were perhaps the greatest factor that undermined Africa’s take-off in the early 1980s. In Nigeria, for example, “the harshly iniquitous IMF conditions undermined industrialisation projects, unrealistically devalued the national currency and halted growth”, he wrote in a 2016 analysis in Africa Policy Review.

The Chinese lending model in Africa, on the other hand, allows low-income countries to access large-size loans for infrastructure if reimbursement can be guaranteed by lucrative commercial projects such as oil or mines, or export revenues. The infrastructure is then developed as long as the commercial project remains profitable. Experts call it a “mixed-funding” model.

Also, rather than stringent reforms, China allows loan recipients to choose and implement infrastructural projects as they deem fit. “With China, African leaders are able to retain most of their policy-making space,” said Nwoke, who has written on China and Africa and their prospects for a new model of South-South cooperation. He said African nations preferred the “nuance” of China’s loans, which are based on a “win-win philosophy”.

Those alternative terms have challenged IMF’s powers to set debt limits in Africa, and have been embraced by African countries. That “challenge” compelled the IMF to review its norms and make it more flexible, setting off reactions elsewhere, says Johanna Malm, whose PhD, dissertation, When Chinese Development Finance Met the IMF’s Public Debt Norm in DR Congo (2015), focused on China, IMF and Africa.

“Chinese commercial loans challenge the IMF’s lending model because they are more expensive for the borrowing country than the loans that [the] IMF usually allows low-income countries to take up,” she told Africa in Fact. She added that Africa has probably been attracted more by China’s offer of big money than by a tendency to avoid IMF’s so-called neoliberal demands.

“Of course, there is also the IMF’s normative approach to debt, but I would say that the main reason why African countries have turned to Chinese banks is that they can offer much bigger loans and take more risk than Western development finance institutions can,” Malm, who now works as senior adviser with the Swedish National Audit Office, told Africa in Fact.

In Africa, China’s “mixed-funding” is known to have first been applied in Angola. The southern African country turned to China after the IMF demanded tough reforms. Between 2004 and 2010, the war-battered country received some $10,5 billion from China’s Exim Bank, with its oil as collateral. What experts would later refer to as the “Angola mode” was replicated with modifications in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 2007, where China offered financing for a mining project and infrastructure construction.

Malm said both sides agreed that the infrastructure projects would only be financed as much as the mine – Sicomines, a joint venture between DRC and China’s Exim Bank – remained profitable enough to ensure repayment. That meant the total worth of the credit, interest rates and grace period of the loan were not fixed. A sovereign guarantee committed the DRC to full repayment of the loan – should the mine fail to generate enough profit – by 2032.

In her dissertation Malm showed that the IMF demanded the removal of sovereign guarantees before forgiving the DRC’s $12,3 billion debt. The DRC later agreed and also downsized the Sicomines agreement to $3 billion, Malm says.

But her study also found that the IMF had manipulated its own assessment to portray the renegotiated loan as a low-cost and concessional loan, to meet its debt terms. “The IMF made this silent compromise because the political and economic importance of the Chinese loan made it impossible for the IMF to ask the DRC to downsize the Chinese loan even further,” Malm wrote in her follow-up research in How Does China Challenge the IMF’s Power in Africa?

A month after the DRC settlement, a bolstered Angola adjusted its agreement with the IMF too, making the limit placed on its non-concessional loan subject to review. By December that same year the IMF revised its debt limit framework, making it more flexible. In 2010, after the DRC and Angola’s successes, Ghana also turned to China for a $3 billion “mixed-funding” project. The first tranche of $850 million again defied the IMF’s debt limit of $800 million agreed with the country.

In recent years more African countries, including Nigeria, Zambia, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda and Ethiopia have turned to China.

While individual countries do not always release details of the deals, the China-Africa Research Initiative said Chinese loans to Africa rose from $139 million in 2000 to $11 billion in 2012, and to $17 billion in 2013, before falling marginally to $16,6 billion in 2014.

The biggest loans have been offered to Angola, Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, Ghana and the DRC. By 2014 Angola had received $21,2 billion and the DRC $4,7 billion.

But fears are mounting that Africa is loading itself with the heavy debts arising from the huge loans. In its October 2016 Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa, the IMF urged the right balance “between much-needed developmental spending and hard-won debt sustainability”. It noted that while loan commitments by China have decreased in some sub- Saharan African countries since the spike in 2013, they have risen in others.

“The Republic of Congo and Mozambique saw official loans disbursed by China decrease by more than two-thirds in 2015 compared with 2014,” the IMF said. “In contrast, they were expanded significantly among countries of the East African Community (Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania).”

According to David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Washington DC-based Brookings Institution, Africa can – with prudent management – increase its borrowing without raising the foreign debt to GDP ratio.

“The trick for African countries is to find the middle ground between financing and debt. With improved institutions and policies, the typical African economy has been growing at a healthy rate of five to six percent per year in real terms since 2000,” he said in a 2016 study, China’s Engagement with Africa From Natural Resources to Human Resources.

“Add in some modest inflation, and nominal GDPs are expanding at close to 10% per year. Hence, there is significant potential to increase foreign borrowing without raising the foreign debt to GDP ratio at all.”