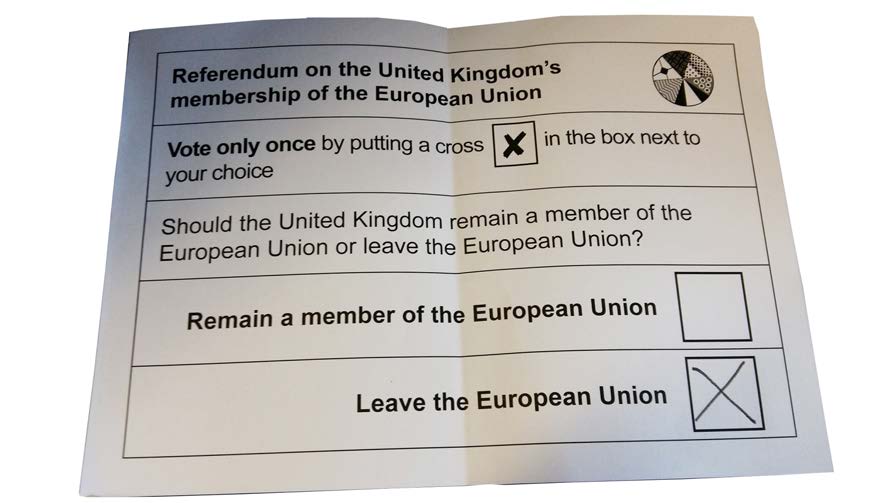

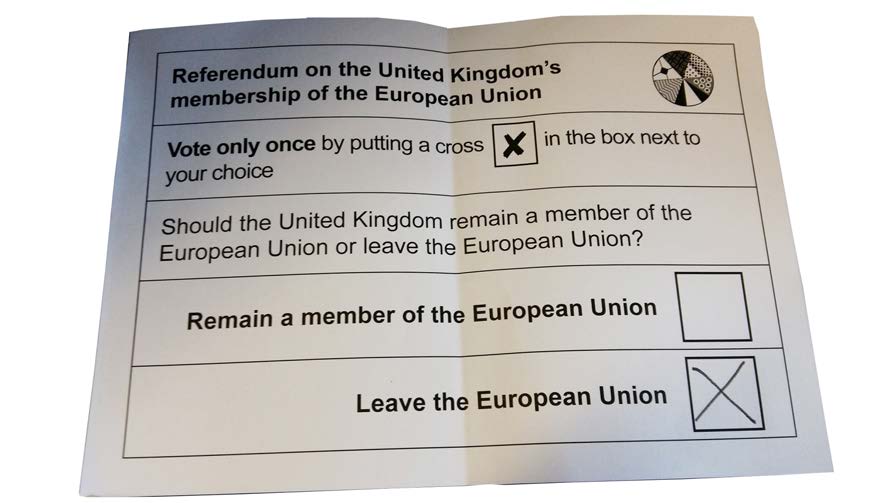

Britain leaving the EU sent shockwaves worldwide © Mick Baker, Flickr

The UK’s unexpected exit from the EU raises questions about whether the AU’s lofty integration ideals resonate with ordinary Africans

On 24 June 2016, the world awoke to the unexpected news that the United Kingdom (UK) had voted to leave the European Union (EU). Global financial markets took a tumble, currencies fell, the British prime minister resigned, and UK and EU civil servants braced for years of legal wrangling.

Africa wasn’t spared the aftershocks — the South African rand depreciated. Trade negotiators across the continent are now pondering the future of existing deals with the EU and the prospect of negotiating separate deals with the UK. This raises the question: what does “Brexit” — as the British exit from the EU is known — mean for Africa’s own journey towards greater integration?

One lesson is clear already, says Calestous Juma, professor of the practice of international development at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Africa should beware of having a central institution that issues directives to member countries, he argues. An institution like the African Union “could make suggestions”, but if they were binding this would “create problems”. “In the East African Community (EAC), there is a provision for a federation.

Polls have shown that when it comes to economic integration, people are very enthusiastic, but as soon as you bring up political integration, that enthusiasm disappears.” The tripartite free trade area agreement between regional blocs EAC, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa and the Southern African Development Community was negotiated at “record speed”, says Juma. But he adds that this was only possible because the negotiations did not involve proposals for political integration.

Caroline Waiganjo, programme adviser at civil society coalition State of the Union, agrees. “When the EAC was discussing the issue of the single passport, people were asking ‘why bother with one passport? Can’t we just make it easier to travel?’ There is a reluctance to let go of nationality,” she says.

In its 2015/2016 round of surveys, independent research network Afrobarometer found that only 38% of respondents supported the idea that each African country had a duty to guarantee free elections and prevent human rights abuses across the continent; 58% argued the need to respect national sovereignty.

Juma argues that this desire to strengthen the nation state while at the same time advancing the continent’s economic integration has much to do with its history. “Africans had their identities disrupted through colonialism. It might therefore seem contradictory to hold on to post-colonial states, even though we didn’t create them and we whinge about them all the time, but what’s the alternative? “Going back to reconfigure different ethnic groups would lead to conflicts,” he says. Africa, he suggests, should pursue integration as a “loose network, not a strict hierarchy”.

Jan Hofmeyer, head of the policy and analysis unit at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation based in Cape Town, South Africa, says the Afrobarometer findings show that the rhetoric at AU level isn’t aligned with sentiments on the ground. “We have very lofty ideals in terms of Agenda 2063 and what we want to achieve, but the big lesson from Brexit would be not to rush integration [but to] do it slowly [and] incrementally,” he says. “And that’s something that must be done in tandem with economic development, otherwise it will be perceived as something that benefits the elite.”

Worryingly, the recent Afrobarometer survey also found that 30% of Africans didn’t know enough about the AU to form an opinion about it. This correlated with their access to news. Among people who never listened to the news, 49% thought the AU helped “a little bit”, “somewhat” or “a lot”, compared with 64% of those who listened to the news every day. Perceptions among those who did have an opinion about the AU varied widely from one country to another.

Liberia rates the AU highly compared with the rest of the continent, with 80% of the population there saying that the AU helped “somewhat” or “a lot”. Osai Ojigho, a governance adviser and coalition coordinator at State of the Union, says this is more likely to happen in countries that have received AU assistance. Liberia received AU peacekeeping assistance during the civil war from 1999 to 2003, and medical assistance during the Ebola crisis. Conversely, in sceptical North Africa, a third of respondents thought the AU didn’t help at all.

In the light of Brexit and the disconnect that emerged between citizens and institutions perceived as aloof, Ojigho says that the AU will need to be more proactive about communicating and engaging with Africa’s citizens. She adds that its capacity has been an issue, especially with regard to producing material in multiple languages.

However, the AU doesn’t appear to have taken any lessons from Brexit, says Waiganjo. It was instead focused on the election of its next chairperson while the referendum that led to the UK’s exit from the EU was taking place, she explains. Also, she says, “[the AU] is still ‘high’ on the launch of Agenda 2063”. “They feel that it is a concrete roadmap and it is blinding them to [other] issues.”

A recent surge in interest in the union — Morocco’s formal application to re-join after its twenty-two-year absence; Haiti’s (unsuccessful) application in 2015; and Israel’s request to join as an observer — shows the institution appeals to leaders, she adds. But the continent’s citizens “are against a certain kind of regional integration”. “They’re happy [for the AU] to intervene when there is conflict, but when it comes to leaders increasing their constitutional terms in office, they’ll say, ‘no, let us deal with our own leadership issues’.”

Juma argues that the AU should focus on peacekeeping and leave economic matters to regional blocs. This would slim down its secretariat — which might become an imperative as the institution tries to reduce its reliance on foreign donor funding. The EU is a big contributor to the AU and there are concerns that Brexit may affect its foreign aid budget. Meanwhile, Hofmeyer and Waiganjo agree that it is unlikely AU member countries will consider their own exits, mirroring the UK’s exit from the EU. True, South Africa grumbles about the cost of AU membership — it paid R195 million in 2014/2015, according to the department of international relations and cooperation — and jokes about African “AUxits” did the rounds on the fringes of the Kigali summit.

But “most people … realise the complexities in Africa with regard to good governance and corruption and they want a big brother that is not the International Criminal Court,” Waiganjo says.

The union is also a vehicle for African solidarity in the face of adversity, says Ojigho: “[It] gives Africa leaders back-up, good or bad.”