Self-determination and identity are deeply emotive issues, and the choices people make in this regard, however controversial, require respect

It was already over two years since the boxer formerly known as Cassius Clay had converted to Islam and started calling himself Muhammad Ali, but the white press and some establishment blacks persisted in using his old name, to his annoyance. One of the detractors, the boxer Ernie Terrell, a black man himself, was to learn the hard way when he met Ali in the ring in Houston, Texas, on February 6, 1967.

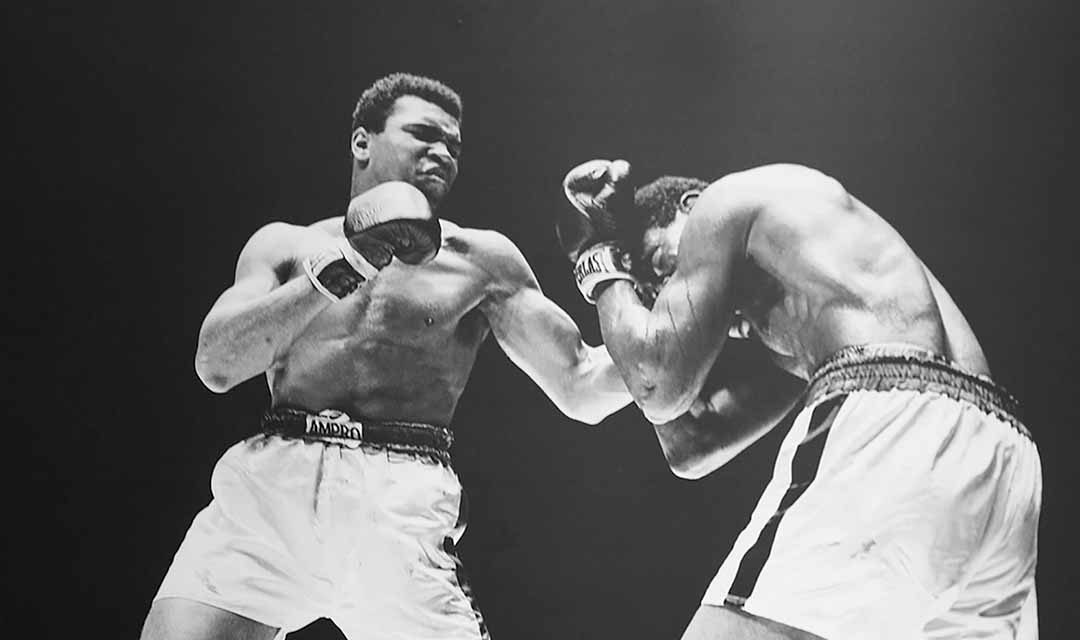

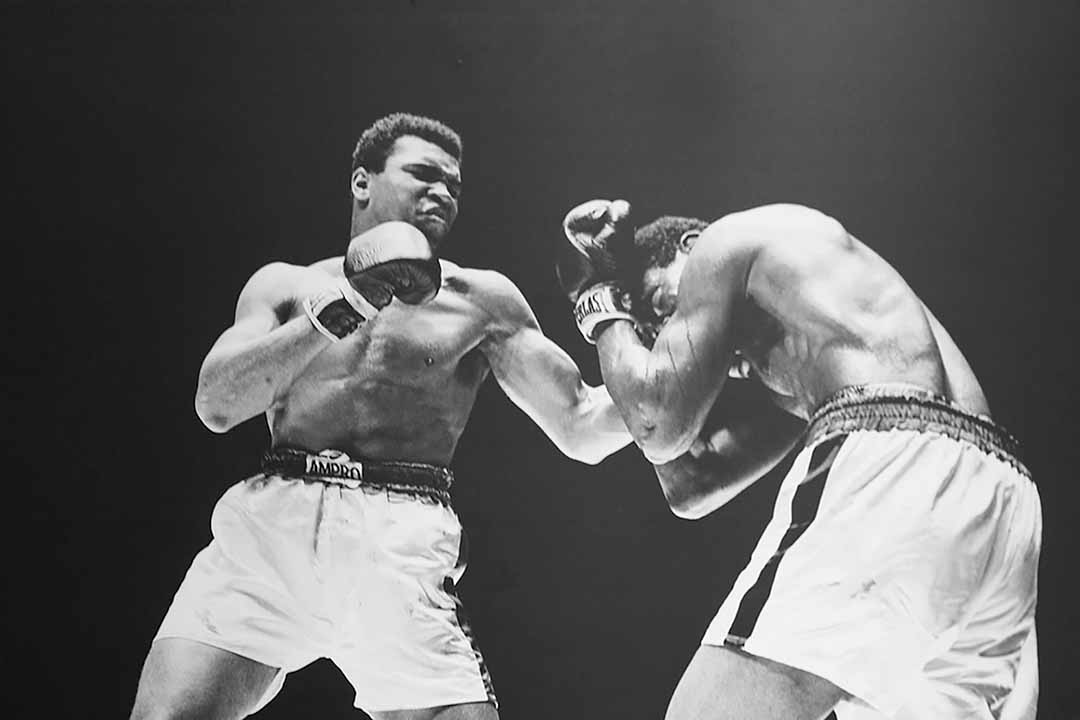

As soon as the fight began, Ali showed he was a superior boxer to Terrell – but restrained himself from knocking him out. He had a plan. As Kevin Mitchell recounts in his book How to Think Like Muhammad Ali: “In the eighth round (Ali) unleashed his ultimate spear: ‘What’s my name?’ he inquired of Terrell. ‘What’s my name?’ Over and over again, he demanded that he pay homage. ‘What’s my name?’ You could hear it on the TV broadcast.”

Winning the fight after 15 gruelling rounds, Ali was roundly condemned for his cruelty and barbarism. After watching the fight myself, a part of me agrees with the criticism. But at a deeply emotional level, I can identify with Ali. His own anger, and determination to “make an example” of Terrell, came from a rational premise. Having converted to Islam, which also saw him discard what he called his slave name, and speaking openly against racism in America, he expected his black brethren, especially those in prominent places like Terrell and others, to join him in his ideological fight. At the very least, they could express this support by using the name he had chosen – but they generally laughed in his face.

His decision to embrace a new identity was a calculated move, the beginning of his long fight with the establishment. To the day he died, he never regretted the fact that he’d refused to go and fight in Vietnam, an act that got him branded as unpatriotic. To the surprise of many – especially in progressive circles – he also refused to participate in the civil rights movement: “They want me to carry signs. They want me to picket. They tell me it would be a wonderful thing if I married a white woman because this would be good for brotherhood… I just want to be happy with my own kind.”

Ali had drawn the line: no integration for me. To further stress the point, in yet another interview, he said, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be.” This was a refrain that would later be adopted and popularised by the author James Baldwin, when he said, “I am not your Negro.”

I am invoking Ali’s narrative because it speaks directly to the deep emotions that bubble to the surface whenever we talk about identity. How we identify ourselves, and how we want to be perceived by others – in other words self-determination – is crucial. When people decide they do not want to be referred to as “he” or “she” any longer, we should respect that. When a person previously called African chooses another identity, we should also respect that.

Some years ago my buddy Mondli Makhanya and I subjected ourselves to a dinner date with Steve Hofmeyr, the musician. As the drinks flowed, we inevitably started talking politics, a dangerous subject if your interlocutor is Hofmeyr. He expects you to look at things from his perspective, and he always wants to win. At any rate, he wanted to know: what do you guys define yourselves as?

I said I was a black South African. Mondli said he was a South African. But no, that was not enough for Herr Hofmeyr. “But you guys both have Zulu surnames; why are you ashamed of such a heritage?” He went on to say that we three were all in the same boat, because Zulus and Afrikaners had for a long time been marginalised and made a laughing stock by the “wily Xhosas and their English brethren”.

Now tempers were rising. “Yes, Zulu is my language and I am proud of that, but you’re not going to tell me how to define myself,” I responded angrily.

Mondli stuck to his original position: “I am a South African and that’s where it ends.”

The night ended on an unnecessarily acrimonious note, with Hofmeyr claiming the last word: “You guys are in denial of who you are”. Driving home, I was still smarting over what many might have dismissed as a non-event. My angry rumination found me clawing back to a 2005 essay by Taiye Selasi, which I sought out the following day, and reread.

In it, she wrote in part: “… the Afropolitan must form an identity along at least three dimensions: national, racial, cultural – with subtle tensions in between. While our parents can claim one country as home, we must define our relationship to the places we live; how British or American we are (or act) is in part a matter of affect. Often unconsciously, and over time, we choose which bits of a national identity (from passport to pronunciation) we internalise as central to our personalities. So, too, the way we see our race – whether black or biracial or none of the above – is a question of politics, rather than pigment; not all of us claim to be black.”

When Selasi declared herself an Afropolitan many dismissed her choice of identity as a nonsensical, self-congratulatory label. An African who by accident found herself in the United States, they expected her to choose if she was black or not. Generally, Afropolitans are those people of African parentage who are born overseas; they might go to university in the US or the UK, and then find themselves working in Canada. One would call them citizens of the world, except that is rather insipid, and less specific.

Indeed, identity is contested terrain. Many of us have long been in these trenches of identity warfare. In our early encounters with our conquerors – because they couldn’t pronounce our names or were wary of the obvious pride that we derived from those names – they decided to strip us of these “heathen” identities, and anoint us with “proper, civilised Christian names”. Almost overnight, we found ourselves groaning under the yoke of Jim, Frederick, Margaret, Nelson and many of the foreign names that didn’t mean anything to us.

Language and some traditions and customs were the only part of one’s identity that the conqueror couldn’t wrench away from us. So we held on to that. And celebrated it. But when the apartheid regime tried to latch onto the tribal identity, to justify their policy of separate tribal homelands, we danced around the ring like Ali and punched them in the face with the collective fist of black power. We proclaimed: “We are not Zulu; we are not Tswana; we are not Pedi. We are black!”

When one got sucked into the exhilarating maelstrom of black consciousness, the world was suddenly filled with so many possibilities at how one defined oneself. You would have noticed that this evolution is always necessitated by the environment that one finds oneself in, the stimulus. Whiteness never existed until white people got out of Europe and encountered those who were different from them. Then, voila, they were white! Whiteness was used as a tool to firstly alienate then subjugate “the other”.

Sisonke Msimang, author of the popular Always Another Country, has weighed in on Afropolitanism. In an essay on the blog Africa is a Country, she wrote in part: “…group identities are constructed. However, some group identities run away with us. Some become harmful, or even work against the purpose they were created to defeat…[T]he ‘Afropolitan’ is just such a group identity. It is exclusive, elitist and self-aggrandising.”

Elitist it might be, but my sense is that it is meant to inspire. It’s not an end in itself. In its early days, black consciousness as espoused by Steve Biko and his comrades was also seen as elitist. In fact, it took some time for locals to warm up to it, because it couldn’t even articulate itself in many of South Africa’s indigenous languages. That hurdle is long behind us, and BC texts are now available in various local languages.

Therefore, I have no problem with the notion that Afropolitanism is exclusivist. Trailblazers in any society have always, on first blush, been perceived as elitists. Given time, Afropolitanism will begin to resonate with even those African immigrants who might not necessarily be educated – but can trace their ancestry to Africa, and are plying their trade across the four points of the compass.

FRED KHUMALO is a seasoned journalist and award-winning author of the novels Dancing the Death Drill and Bitches’ Brew, among other titles. With an MA in creative writing from Wits University, he is also a Nieman Fellow (Harvard University, 2011-2012). A stage adaptation of Death Drill had its world premiere at Nuffield Theatre and Southampton