French President Emmanuel Macron (second right), International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director Kristalina Georgieva (left), Senegal’s President Macky Sall (right) and African Union President and President of Democratic Republic of Congo Felix Tshisekedi (second left) at the Summit on the Financing of African Economies in Paris, May 2021. Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP

Two meetings of African leaders in May and July on the region’s post-pandemic economic recovery strategies were not short on big declarations. In Paris, the first summit, facilitated by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, promised to rally global financial support to replenish Africa’s depleted coffers under a “new deal”.

Macron pledged to persuade richer countries to reallocate $100 billion in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) special drawing rights to African states, triple the amount allocated to the continent. The second meeting in Abidjan called for $100 billion in the World Bank’s hardship funding. Typically light on concrete commitments, both events made one point nonetheless: African leaders seemed clear on the scale of the economic challenge the continent faces from a pandemic that has caused relatively fewer African deaths, but has ravaged its economy.

“This is a great opportunity for Africa,” Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi, head of the African Union, said after the Paris event, lamenting how the pandemic “left our economies impoverished because we had to use all the means we had, the few means we had, to fight against the disease.”

African nations have largely been spared the high levels of infection and death caused by COVID-19 in other parts of the world. But lockdowns and reduced economic activities in 2020 pushed the continent into its first recession in a quarter of a century. Africa had six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies before the pandemic began. As the region’s gross domestic product tumbled by 3.7% in 2020, employment fell 8.5%, and debt reached 58% of the gross domestic product (GDP), according to the World Bank. The IMF estimates Africa needs $300 billion for its recovery.

“Undeniably, the economic costs to the continent in the form of lost tax revenues partly occasioned by reduced capacities of businesses (SMEs), a significant fall in tourism receipts, and export revenues inter alia require pragmatic policy interventions to revamp the various economies in the region,” says Edward Nketiah-Amponsah, associate professor at the Department of Economics, University of Ghana. The region has been particularly vulnerable because of its economic model that rests largely on the export of commodities like crude oil, minerals, and agricultural produce, and on tourism.

The failure of African states to open their economies into a broader range of sources of production, trade, and revenues has made it problematic to respond to external shocks. Powerhouses like Nigeria and South Africa paid a heavy price after the pandemic curbed commodity demand, and cut revenue needed to spend on critical sectors and fight the virus. Restrictions on travel also significantly crashed economies that are tourism-dependent, like Seychelles, Mauritiuus and Kenya. The continent’s huge debt made things worse, locking away resources needed to finance developmental projects and fight the scourge.

In November 2020, Zambia became the first African nation to default on debt repayment since the pandemic began. A post-COVID-19 economic recovery must be driven by policies that take advantage of opportunities created by the pandemic, and a good place to start is diversification, experts say. “The importance of economic diversification and structural economic transformation is no longer an issue for debate,” says Njuguna Ndung’u, a former governor of Kenya’s central bank in a September 2020 article. “Business as usual in post-pandemic recovery will only reinforce economic hardship.”

For Africa, the idea of diversification is not novel. African countries have for decades touted economic diversification, but that has never happened. The continent is home to eight of the world’s 15 least economically diversified countries, according to the IMF’s 2020 Export Diversification Index. Only a few countries, like South Africa, Kenya and Tunisia, are relatively better diversified, with their economies spanning natural resources, agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism.

Even so, they have more to do compared to other regions of the world. Most other economies in the continent have remained perilously centralised, and decades-long plans for diversification were never seen through. “Every time there is a crisis, it’s like a song: ‘We must diversify, we must diversify!’ But after the crisis, we forget,” Akinwunmi Adesina, the president of the African Development Bank, said in a recent interview with Africa News.

In a speech at the European Union-Africa Green Investment Forum in June, Adesina said the pandemic presents opportunities for the continent, and listed energy, agriculture and infrastructure as areas of high investment potential for a post-pandemic recovery. “Africa is a huge market offering incredible opportunities. The recovery pathway offers enormous opportunities,” he said. But to take full advantage of these opportunities, other steps are needed, analysts say.

First, Africa needs to rework its value chains. The pandemic has shown the risks of over-relying on a few global economic regions to supply certain goods and services. African countries can be self-sufficient by becoming both the users and suppliers of goods and services. This means that instead of relying on imports, governments can focus on supporting local production, retain profits, and support job creation and growth. Rising protectionism and anti-multilateralism in the West and East has made this even more pressing. “The post-COVID-19 era requires a paradigm shift that promotes domestic production of basic consumer goods,” says Dr Uduakobong Inam, senior lecturer at the Department of Economics, University of Uyo, Nigeria.

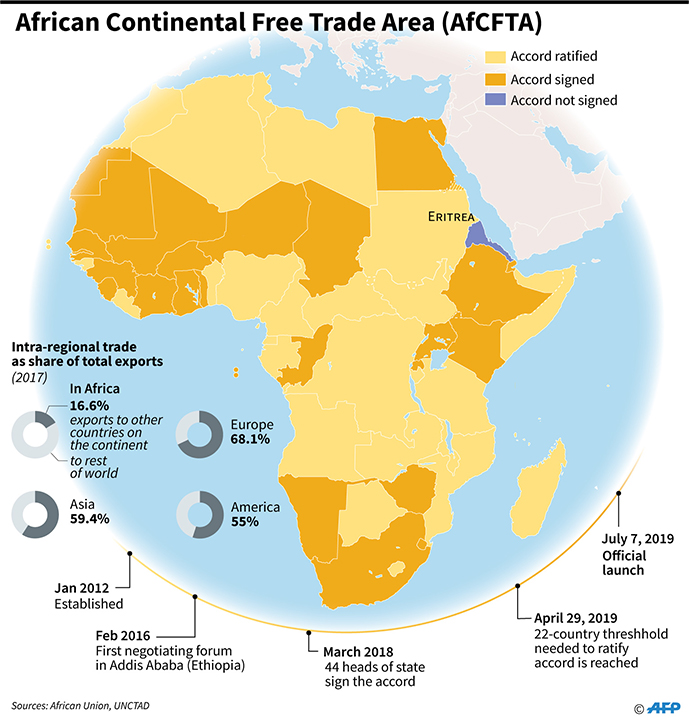

“The short-term and long-term benefits of these efforts are multi-dimensional: value chain development, forward and backward integration, job creation, increased incomes, increased taxes and inclusive industrialisation.” More collaboration is also needed between countries through intra-African trade. The share of intra-African exports as a percentage of total African exports stood at 17% in 2017, significantly low compared to Europe’s 69%, Asia’s 59%, and North America’s 31%, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The recently approved African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), expected to remove tariffs on goods, presents a great opportunity.

Governments must also support small businesses, says University of Ghana’s Nketiah-Amponsah. By May 2020, 75% of micro- and small businesses that make up the informal sector and account for 83% of private-sector employment in Africa, saw their revenue decline by more than 30%, according to the AU’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development. State support to them can be in the form of direct credit or risk-guarantees for third-party lending. “Providing loans to these SMEs to be repaid within two years, with a one-year moratorium before repayment, is a step in the right direction,” he says, citing a similar initiative by the Ghanaian government.

Another opportunity to be seized is digitalisation. Besides shutting down businesses, pandemic-induced lockdowns served a useful purpose by driving many sectors online. Prospects remain for digital acceleration in retail trade, agriculture, education, and finance. Financial technology has recorded a significant boost as more people have adopted digital payment and purchasing platforms. That growth saw two companies, Egypt-based Fawry and Nigeria-based Flutterwave, hit $1 billion valuations in 2020, only the third and fourth tech start-ups in the continent to achieve unicorn status.

Providing digital infrastructure and policies to enable further growth in the sector is expected to hasten and boost post-pandemic recovery and economic growth. “Indeed, the desire for economic recovery in Africa brings to the fore the need for sustainable technologies within the framework of a robust and dynamic digital economy that disrupts the nature of work in Africa but creates jobs for the teeming youth population,” Inam told Africa in Fact.

Ini Ekott is the deputy managing editor at Premium Times, Nigeria. He has researched and written extensively on governance and leadership in Africa. He is a former Wole Soyinka investigative reporter of the year, and was a member of the global team of journalists that conducted the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers reporting