Rwanda president Paul Kagame receives a COVID-19 vaccination at King Faisal hospital in Kigali, Rwanda, March 2021. Photo: Uruwiro Village/AFP

On 11 March, 2020, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organization (WHO) formally designated COVID-19 as a global pandemic. Citing “alarming levels of spread and severity”, he called on governments to take “urgent and aggressive action” to tackle the crisis. Most countries based their response on the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which allows the restriction of “certain individual rights during public emergencies that threaten the life of the nation to the extent that they are strictly required by the exigencies of the situation”.

Further guidance came from the Siracusa Principles (endorsed in 1984 by the UN Commission on Human Rights), which state that “all public health measures must be relevant and proportionate to the nature and extent of the threat, based on scientific evidence, specifically aimed at preventing disease or injury or providing care for the sick and injured and be neither discriminatory nor arbitrary in application”. Rules must also be subject to regular review. Any proclamation of public emergency and consequent derogations “that are not made in good faith are violations of international law”.

COVID-19 is an infectious, potentially fatal disease for which there is currently no licensed medication. For most of 2020, physical distancing, masks and sanitising were the main protections and, even once vaccines became available, distribution has been limited and unequal. The scale of this pandemic undoubtedly meets ICCPR and Siracusa criteria, so the question is not if, but by how much states may restrict rights. Even with the above international guidelines, establishing proportionate, scientifically valid responses to a new disease and an evolving virus has been challenging.

King Mohammed VI of Morocco receiving Aziz Akhannouch of the National Rally of Independents, tasking him to form a new government after winning the Moroccan election, September 2021. Photo: Azzouz Boukallouch/ Moroccan Royal Palace/AFP

In the course of the ongoing pandemic, there have been many international examples of authoritarian overreach. These transgressions have occurred not only in regimes already considered to be disciplinarian or tyrannical, but also in well-established liberal democracies.

Most work on COVID-19-related authoritarian overreach pertains to Asia, eastern Europe and the Americas. What follows is an assessment of the situation in four African countries (Mauritius, Morocco, Rwanda and South Africa) between January 2020 and July 2021. The countries were chosen to reflect diverse pre-COVID governance models.

Table 1 depicts data from the 2019 Ibrahim Index of African Governance within which Morocco and Rwanda show scores for participation, rights and inclusion that are far below overall governance scores. Morocco (a monarchy) and Rwanda (a de facto one-party regime) represent different forms of authoritarian rule, but both are distinctly different from the more open governance models in pre-COVID Mauritius and South Africa.

The behaviour of leaders and law enforcement agencies were assessed in terms of five areas:

• Legislation: were COVID-19 control laws unduly restrictive?

• Flexibility: were restrictions adjusted in line with disease waves?

• Law enforcement: were those tasked with upholding law unduly heavy-handed?

• Accountability: were law-makers and enforcers held answerable for decisions and behaviour – through parliamentary oversight and press coverage?

• Suspension of democratic institutions: were parliaments closed and/or elections postponed?

A variety of legal frameworks guided country-specific COVID-19 control. The Mauritian parliament introduced the COVID-19 Miscellaneous Provisions Act 2020 and Quarantine Act 2020, which reduced workers’ legal protection, allocated increased discretionary power to Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth and new powers to police (including rights of entry and arrest without warrants).

Trade unionist Ashok Subron observed that, “It is a derogation of our civil rights and liberties, framed under the guise of a public health emergency. This cannot be accepted, even in this current COVID-19 situation.” South Africa’s government used pre-existing Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 to impose sliding scale restrictions. Disaster regulations have been extended monthly by government notice, rather than parliamentary vote. This could theoretically go on indefinitely. The Rwandan response was not based on specific legislation, but rather cabinet decisions which were issued as instructions from the prime minister’s office.

A Kigali health worker (who would only speak on condition of anonymity) explained that “the government might not admit to it but basically we live in a permanent state of emergency, so there was no need to declare one”. The insistence on anonymity is in itself indicative of the political context. Dr Intissar Fakir, senior fellow and director North Africa and Sahel Program at the Middle East Institute, Washington described the Moroccan pandemic response as “tightly driven by the monarchy, Country Overall governance 2019 which took the agency of elected officials out of the loop”.

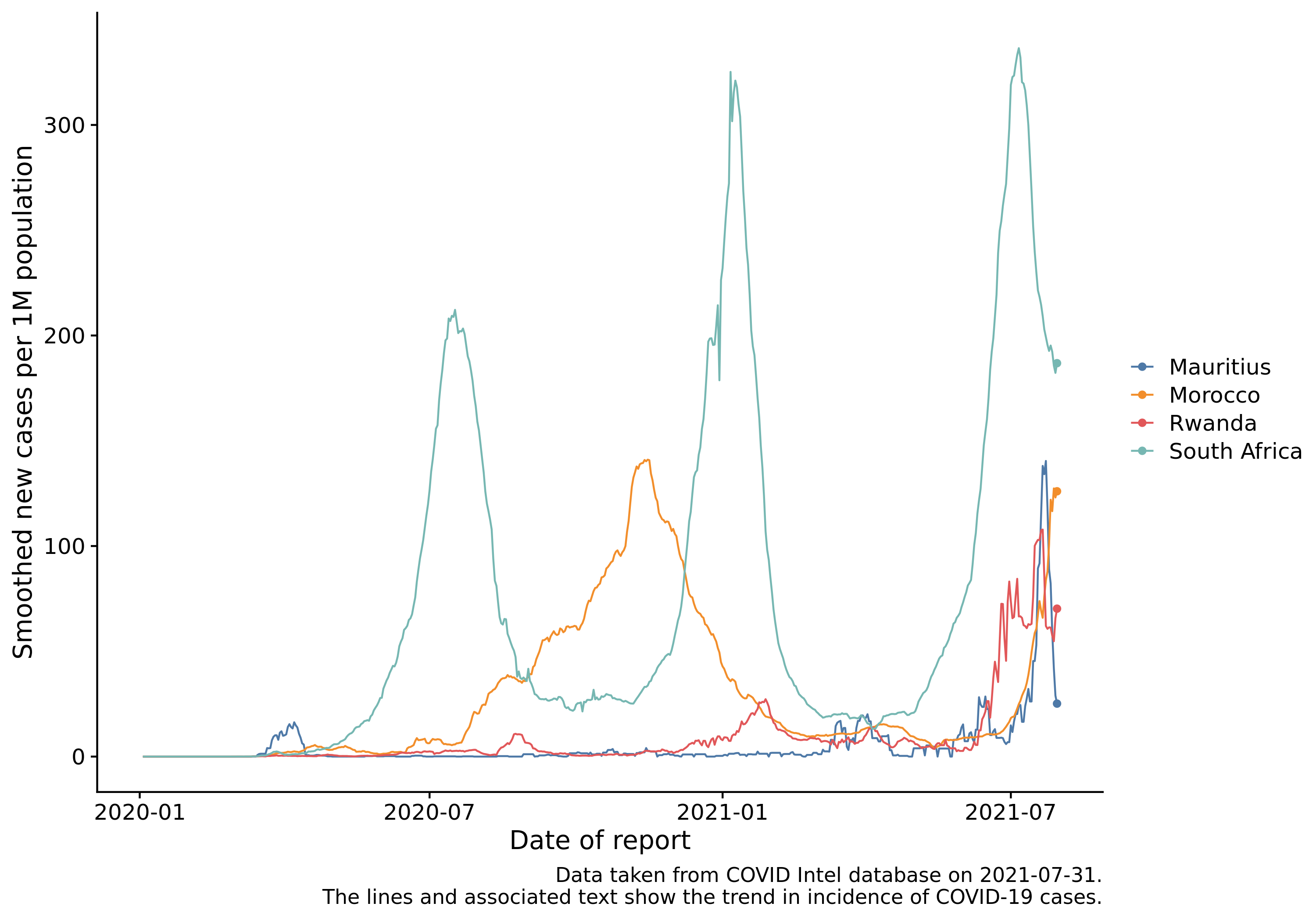

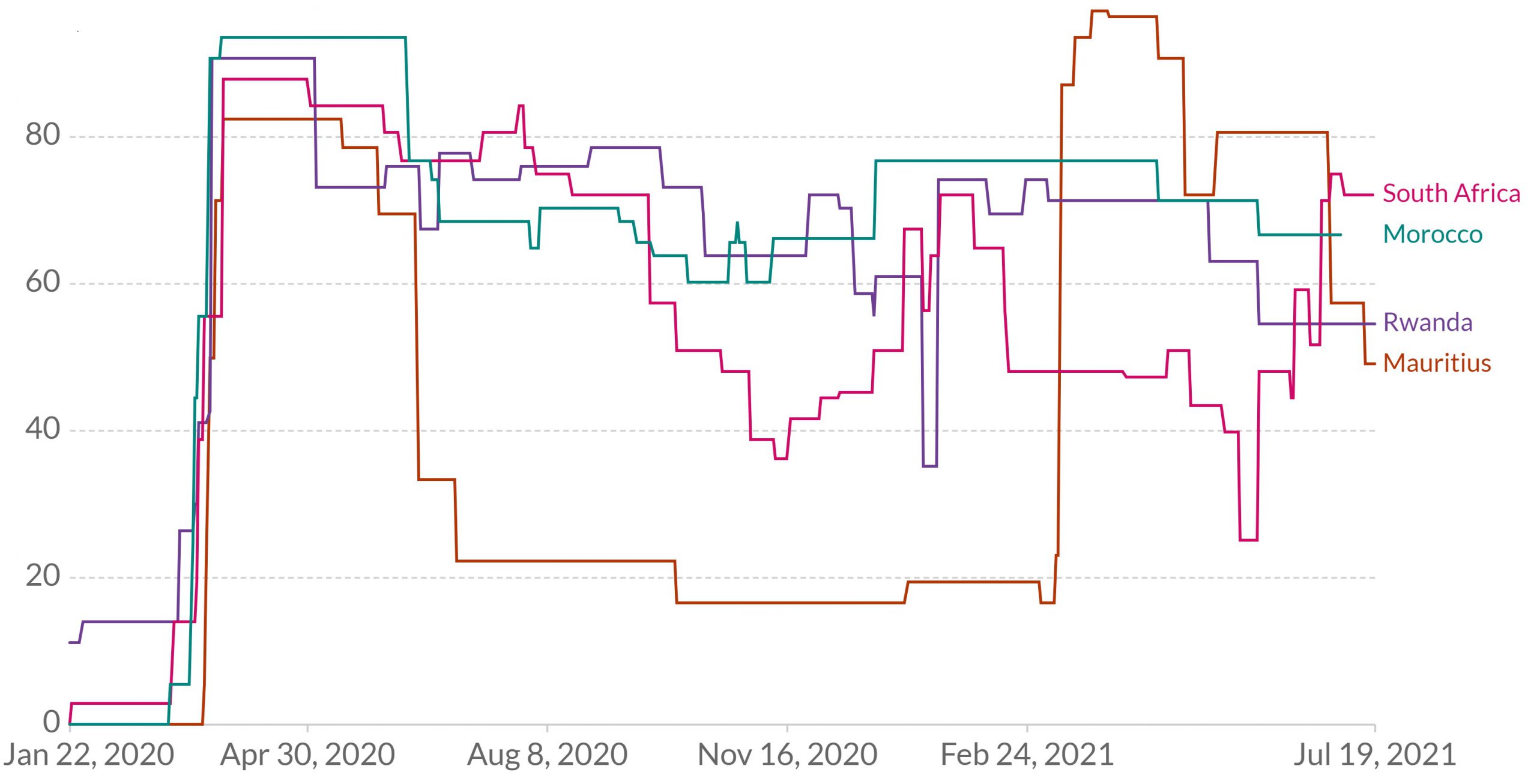

In order to be compliant with Siracusa and ICCPR, public health controls must be proportionate to the threat. COVID-19 manifests in waves, so proportionate responses should see restrictions change with disease ebb and flow. Figure 1 shows the caseload per million of population, January 2021 and July 2021. Figure 2 depicts restrictive emergency measures captured by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Read together, they show South Africa and Mauritius to have had more responsive adjustments than those countries that went into the pandemic with authoritarian tendencies.

Figure 1: Caseload per one million of population by country, January 2021 to July 2021

Figure 2: COVID-19 Stringency Index

Authoritarian arrogance is written into rules that do not take into account the conditions under which citizens survive. Issuing regulations does not necessarily make compliance and enforcement possible. Shifa et al. argue that, “Those with the least resources find it most difficult to conform to lockdown regulations, and yet are most COVID-19 vulnerable.”

Across Africa, low incomes and the high numbers of people who depend on the informal economy pits observing restrictions against survival. In April 2020, United Nations High Commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, identified South Africa and Morocco amongst the 15 countries where security forces flouted the rule of law in relation to corona virus restrictions.

In a briefing on 8 May 2020 to South Africa’s parliament, the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) reported a 32% increase in complaints during the first 41 days of lockdown, compared to the same period in 2019. During this time, IPID received 828 complaints, of which 376 (45.4%) could be directly linked to lockdown. Of these, 280 (74.4%) were for alleged assault and 10 (2.6%) for deaths as a result of police action.

South Africa’s former Press Ombud, Pippa Green, observed that “at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were hardly any cases of COVID-19, “there were more injuries caused by the police than people becoming infected”. In June 2020, Mauritian police tasered two brothers who were objecting to the arrest of their elderly mother who had broken curfew. Images of the attack were widely circulated on social media. The rumour in Port Louis was that the police had posted the recording themselves, in order to intimidate others. Press and social media reports of security force overreach have tapered off, but the lack of comparable data from the start of the pandemic to the present prevents definitive conclusions as to whether it is transgressions or reporting thereof that has declined.

What we do know is that in all four countries, there were promises of action to be taken against police misconduct, but very little evidence of follow through. In Johannesburg, Collins Khosa died of injuries sustained when he was allegedly dragged out of his home and assaulted by soldiers on 10 April, 2020. An army investigation cleared soldiers of wrongdoing. This decision was criticised in the subsequent criminal investigation, but prosecution has been pending for more than a year.

Similarly, the Rwandan president and minister of justice condemned the actions of police exposed on social media as enforcing lockdown with excessive and, at times, lethal force. There were promises of those responsible being held accountable. In September 2020, Amnesty International reported that those investigations were ongoing. No further information on the matter could be found.

Mauritius saw the most significant disruption to parliamentary process. The prime minister repeatedly deflected questions about corruption pertaining to contracts for personal protection equipment (PPE) and ventilators. Opposition parliamentarians attempting to press the point were evicted. The National Assembly was suspended for two months in August, and again in December 2020 for three months.

According to Ashok Subron, since the National Assembly resumed in March 2021, the stifling of executive accountability via parliament under the speaker of parliament, Sooroojdev Phokeer, has worsened. Subron said, “It is increasingly a space where the autocratic speaker’s main aim is to suppress opposition. Questions go unanswered; debates are deliberately turned down by the speaker. Since parliament restarted in March, we have seen expulsions of the leader of the opposition and opposition MPs… It is symbolic of what has happened in the National Assembly under COVID. It is not even a rubber stamp – just a mockery of democracy.”

Governments do not face a test at the polls if elections are postponed. Mauritius cancelled elections due to be held in June 2021. New elections must be held within two years. A new date has not been set. The South African Electoral Commission approached the Constitutional Court for a postponement from October to February 2022. Since then, elections have been set for November 1. Rwanda conducted local elections on schedule and Morocco held elections in September 2021.

Morocco’s parliament passed new legislation containing restrictions on freedom of expression. Law No. 2.20.292 of March 2020 set penalties of three-month prison sentences, and fines of MAD1,300 (around US$146), for breaching “orders and decisions taken by public authorities” and for anyone “obstructing” those decisions through “writing, publications or photos”. At least five human rights defenders and citizen journalists were arrested in April and May 2020 for online and social media posts criticising the authorities’ handling of COVID-19 aid distribution, and were charged under both the health emergency law and penal code provisions for “offending public institutions” and “spreading false information”.

South Africa issued regulations worded thus: “Any person who publishes any statement … with the intention to deceive any other person about (a) COVID-19; … (c) any measure taken by the government to address COVID-19, commits an offence…” Pippa Green observed that, “It is problematic to criminalise ‘misinformation’ when scientific knowledge is changing on a daily basis and many journalists felt that the law inhibited their ability to question government actions.”

In Rwanda, journalists possessing authorisation to work, or wearing press credentials, have been arrested for allegedly violating curfew restrictions. Bloggers reporting on abuses within the COVID-19 response have been arrested. The Rwanda Media Commission stated that bloggers were not recognised as journalists, and thus “not authorised to interview the population”.

Mauritian investigative reporters have been harassed, and private news/talk radio stations have been threatened with having their broadcast licences revoked. All over the world, including in Mauritius, Morocco, Rwanda and South Africa, there have been violations of the Siracusa and ICCPR guidelines. Preventing permanent expansion of overreaching government power is now an international human rights priority. The arrival of vaccines has raised hopes in those countries with high levels of immunisation that as disease prevalence falls, emergency restrictions will be removed and authoritarian overreach can be pushed back.

In Africa, it is estimated that it may take until 2023 for the continent to be adequately vaccinated. This will drag out the damage to lives and livelihoods and sets up a two-speed global economic recovery. But also, while immunisation rates remain low, disease prevalence will stay high and public health restrictions will, per force, continue to curtail rights. The longer curbs on civil liberties go on, the greater the risk that they will outlast their original purpose and become entrenched as the new normal. Watch this space…